Benjamin Corey wrote a post that offers an explanation of the popularity of end-times Christianity:

The end times version of Christianity that many of us grew up with has been immensely popular, not because it’s true, but because it’s easy. Prior to the invention of end times fanaticism, Christians were busy trying to change the world on a massive scale- changing broken social systems, uplifting the poor and oppressed, and addressing all sorts of other problems they referred to as “social ills.” They labored to help those around them experience God’s will on earth as it is in heaven, the presence of the Kingdom of God here-and-now, and the transformative nature of God’s reconciliation– all things that were truly Good News in every respect.

But Christianity within an end times paradigm? Things went radically down hill after Darby’s teachings caught on because the alternate version of Christianity is so much easier. I used to live that kind of Christianity, and it was cake.

In fact, I remember traveling on a missions trip to the former Soviet Union just within a year or two after the fall of communism. The economy was in shambles, people were hungry, unemployed, and desperate. What did we bring them? We brought them a message of “good news” conveyed through street skits/silent drama and singing “People Need The Lord” to a boombox (remember those?). After our presentation we’d grab a translator and quickly try to get as many people as possible to ask Jesus into their hearts before moving on to the next place.

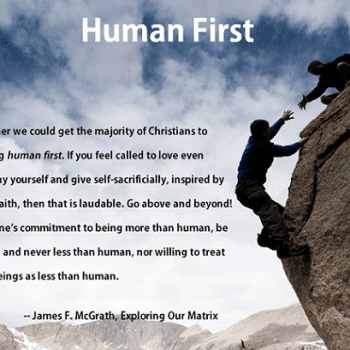

Supposedly, that was all good news. However, what I’ve learned as an adult is that the Good News isn’t about escaping the world, it’s about transforming it. The Good News is an invitation to empty oneself the way Christ did, and to be agents of reconciliation who act as a soothing balm on hurting lives.

Fred Clark shared thoughts along similar lines, talking about how some Evangelical Christians try to liven up their mundane lives by imagining that they are key warriors in a spiritual battle with demonic adversaries:

Deceiving the elect is actually Wall’s entire agenda there — with Deception No. 1 being the idea that they are, exclusively, “the elect.” As such, she urges them to accept that they are immune to deception — that they have unique access to the meaning of scripture and “the testimony of Jesus Christ.” Others have fallen away, bowing to “none other than Satan himself.” But we — Wall and anyone who accepts her invitation to participate in this deception — we are “the remnant that keeps the commandments of God.”

The self-aggrandizing fantasy here would be hilarious except for the fact that so many people aren’t in on the joke. Not only do many white evangelical Christians see this fantasy as deadly serious, they’ve accepted the bargain being offered by Wall and countless others — the agreement to help one another fantasize that their otherwise unremarkable lives set them apart as ultra-special saints who are better than everyone else.

It’s easy to see how such fantasizing can be briefly intoxicating. I fully understand the allure of imagining ourselves to be exceptional. Most of us understand this — just look at our most popular stories, from Star Wars to Harry Potter to Buffy to Cinderella in all its endless iterations.

But it’s one think to relate to the longing that Luke or Harry or Cinderella feels and to indulge in those escapist fantasies. It’s something else entirely to decide that you actually are a Jedi knight or a wizard or a princess, and then to try to sustain that fantasy throughout your daily life. Your daily life usually won’t cooperate with such a pretense.

Sustaining the kind of fantasy Linda Wall invites her readers to indulge in takes an enormous amount of imagination. It requires the collaborative effort of a community of fantasists who agree to cooperate by reinforcing one another’s fantasies. And it requires a willingness to reinterpret every mundane detail of the world around you into something fraught with all the drama of the pageant you’re creating in your head.

Both posts are really about the same thing. Many Christians, instead of transforming the world, choose the easier route of believing the world cannot be transformed except through preaching which one can do briefly and then leave, hoping for the best. Many Christians, instead of examining themselves and seeking to root out the evil within ourselves, prefer to proudly embrace the role of heroic warrior against enemies who in turn are demonized.