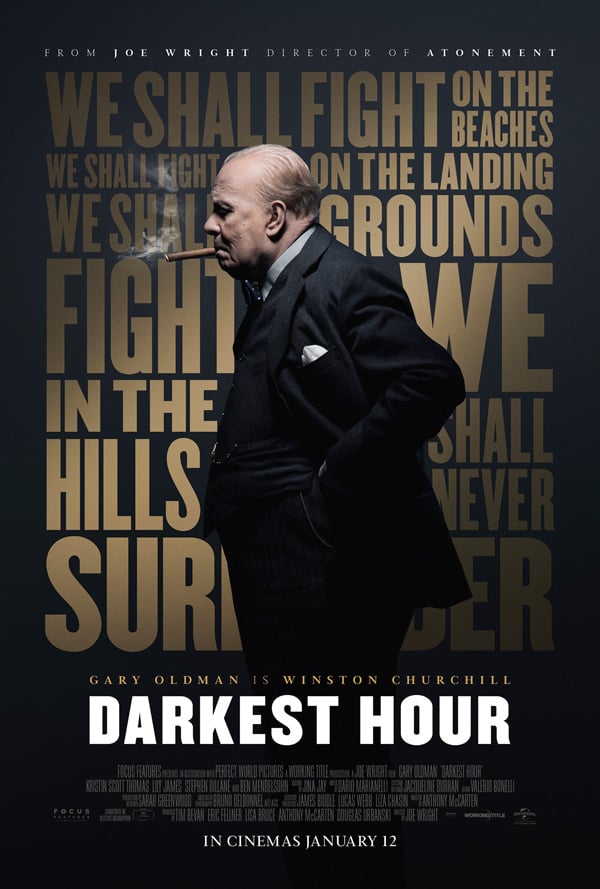

I was delighted to have the opportunity to see the new movie Darkest Hour before it opens in theaters tonight. I had been looking forward to seeing it, ever since I first saw publicity about it showing Gary Oldman, with prosthetics and makeup to turn him into Winston Churchill.

I was delighted to have the opportunity to see the new movie Darkest Hour before it opens in theaters tonight. I had been looking forward to seeing it, ever since I first saw publicity about it showing Gary Oldman, with prosthetics and makeup to turn him into Winston Churchill.

The movie focuses on a relatively short period in May 1940, starting with the British parliament’s loss of faith in prime minister Neville Chamberlain. After some discussion and much reluctance from both his own party and the king, Winston Churchill is appointed as prime minister and invited to create a government, because he is the only person that the opposition will support. More than in other films (or television shows like The Crown), Darkest Hour emphasizes Churchill’s command of the written word and delivery thereof in speech, in contrast with his regular inability to find the right word while speaking. Words and communication seem to me to be at the heart of the message of the film, and this is reinforced by the minimalist soundtrack by Dario Marianelli – and by the powerful use of silence in moments when other filmmakers and film score composers would have chosen to interject music to create emotion. The absence of sound effectively reinforces the power of things like the human voice, as well as of eye contact and other forms of non-verbal communication.

The movie is very much focused on Winston Churchill, trying to give us a perspective that allows us to see him as human and not merely as myth and memory. Within that framework, the movie highlights his gifts as a speechwriter but contrasts this with his weaknesses and shortcomings, and the sacrifices his family had to make for him to have the (up until that time relatively unremarkable) political career that he had had. Early in the film, while his wife (who clearly loves him dearly but is also able to push back against some of his tendencies) says “he is a man like any other,” Winston himself asks while in the process of choosing a hat from his collection of many, “Which self should I be today?”

The bulk of the film focuses in on his difficult decisions and on his brilliant communication through certain media and in certain contexts, often in marked contrast with others. Although I took notes while watching the movie, there were quotes which stuck in my mind without need to look at what I had written to recall them. Phrases such as “How many more dictators must be wooed, appeased…You cannot bargain with a tiger while your head is in its mouth,” “Lost causes are the only ones worth fighting for,” or “those who never change their mind never change anything.” It is easy to disagree with the literal meaning of these statements – and yet to recognize the power and perhaps even validity of their point to at least some degree. It is a question that people will always face: is it better to sacrifice our lives than to sacrifice or abandon our values?

The power of political rhetoric, its relation to truth and information, and matters of hope, values, and tyranny are given particular attention, in ways that both reflect and speak to our current age. Indeed, the question of reflecting vs. influencing the voice of the people is itself a major matter of focus, as Churchill rides the Underground and asks ordinary people a variety of questions, and then tells this story to his Outer Cabinet and eventually to Parliament with similar effect. Has the voice of the people influenced him, he them, or both? Earlier in the movie, Churchill had said that he wants to inspire in the people a feeling that they don’t know they have, which highlights the fact that any answer we might try to give to the question that the movie poses – who influences whom, or do both equally influence each other – gets lost to our view in the human subconscious and the less visible elements of sociocultural values.

Other things that are highlighted include the machinations of members of Churchill’s own party, and his decision (somewhat forced by circumstances, but in marked contrast to the tendency of many today) to surround himself with rivals rather than a potential echo chamber. The issue of receiving little or no information, partial information, and the bigger picture view is highlighted as Churchill’s typist breaks into tears after typing his dictated telegram to the commander of troops at Calais letting them know that rescue would not be coming. As we the viewers know, and as she gets the chance to learn, the sacrifice of the battalion in Calais is part of an effort to save almost 10 times as many from Dunkirk. Having been told that it would take a miracle to save even 10% of them, the question of what course of action to take when the ideal – save everyone – is not available; who gets to decide; who should know about what is being debated and eventually decided; and whether we can and should trust in leaders is highlighted. For ultimately Churchill persuaded his nation to stand up to a tyrant, but in a context in which there was no rational basis for thinking they would win. And were it not for Pearl Harbor getting the United States into the war, things might well have turned out differently – in which case we might also remember Churchill very differently.

For those interested in religion, there are moments in the movie that deserve attention, in addition to the central themes of faith, conviction, trust, and truth. The rhetoric that will state that “our policy is to wage war with all the strength that God can give us” raises very serious questions about the relationship between religion, state, tyranny, and violent struggle. And there is a very specific view of God that is brought into the picture when Churchill says (while talking to the king about his parents) “My father was like God – busy elsewhere.” More subtle, but still relevant to this theme, are statements such as that of Churchill’s wife when she says that “with such power you must try to be more kind.” The relationship between power and kindness is not a given, but reflects particular values. But perhaps the most powerful moment is when Churchill’s wife tells him that his inner struggles have prepared him for that moment. She tells him that he is strong precisely because he is imperfect, and wise precisely because of his doubts.

Other elements in the movie are also important to note in our present context. The places where women could not go in the war effort, and the places (such as the pool of typists) staffed entirely by ladies. The 7 million refugees in France, in view of current refugee crises. And in the midst of a film with so much serious subject matter, there is still humor – for instance, when Churchill gets the “V for Victory” sign backwards and gives a cameraman a gesture that in the UK means “up your bum”; or when he says in response to a woman who says her baby looks like him, “Madam, all babies look like me.” The cinematography is also impressive, with a striking number of shots that allow substantial parts of the screen to be blacked out, as though Churchill (whether riding in a lift/elevator, or in an underground room talking to the president of the United States) is boxed in. The frequent scenes in tunnels seem to foreshadow the movement of many into shelters in the years that follow.

At the very end of the movie, after a powerful speech that wins support even from the most determined detractors in Churchill’s own party, one of them asks “What just happened?” The answer that is given is this: “He mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” In an era of echo chambers and partisan politics, of tyranny and refugee crises, of accusations of fake news and uncertainty or overconfidence about whom to trust, Darkest Hour provides insight, challenges, and inspiration. Because its message is ultimately about hope and trust. The figure of Winston Churchill is one that, with hindsight, we look back on as providing crucial, positive leadership in a moment of profound crisis. But in that moment, the question of whether his inspirational rhetoric (which did not initially inform the public of what the king referred to at one point as the “unvarnished truth”) was something dangerous to be feared or something uplifting to be supported and trusted, was as yet unanswered. Darkest Hour thus both challenges us to stand courageously against tyranny, and to dare to trust from a standpoint that admittedly does not have all the information nor all the answers, and often lacks as well any rational or evidentiary basis for holding out strong hope for better things in the future.

In case you couldn’t tell, I highly recommend this movie, which my family also found to be powerful, historically engaging, and of great contemporary relevance.