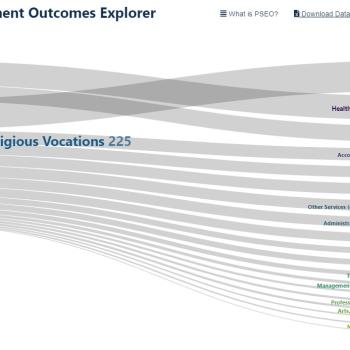

Most readers of this blog will have heard this news: “The University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point plans to address “fiscal challenges” by expanding some academic programs and discontinuing others, it announced Monday. Tenured faculty positions are at stake, with possible layoffs occurring by 2020.” That (rather than comparable developments in Denmark) is presumably what motivated the article by Ryan Craig, suggesting that universities ought to kill, cull, and/or close “underperforming” academic programs. There is, needless to say, a great deal that is problematic in that article. But it also raises a point that I think really does require discussion at universities. To give an example that hits close to home, far fewer students come to university interested in taking courses on the Bible (to say nothing of biblical languages) at my university nowadays than was the case a few decades ago. On the one hand, that might indicate a need to require students to study something they need to know about, yet the need for which they do not appreciate. On the other hand, it might also indicate a change in student interests and demographics that universities need to adjust to. It used to be that the focus in academics and the business world alike was on European languages. The increased recognition of the need to offer more opportunities to study Hindi and Mandarin is surely a shift in a positive direction away from an approach that reflects a holdover from the colonial era. Universities should find ways to add the new and expand growing areas without simply eliminating the old – if you cannot study Classics or German at all at a university, that is hardly an improvement!

And so I think that there is a need for open and serious conversations about how universities should adapt to changing times, in ways that support and respond to positive global trends without simply jumping on bandwagons or pandering to student preferences in a way that treats them as customers to be satisfied even if what we provide to them – at their own request! – is not what they need.

The main thing that made me decide not to simply skim past this article without commenting is the parallel to changing economy and business. At what point does one recognize and embrace the fact that, while we still have use for coal and steel, the demand is not the same as it once was and will never again be as it used to, and embrace difficult but radical reinvention of ourselves?

It strikes me that the approach of a number of Republican politicians to higher education is exactly the opposite of their approach to dealing with such economic challenges. And so I want to make sure that the approach of those of us in higher ed who criticize these politicians does not inadvertently mirror the very stance that we oppose when we encounter it in a domain other than our own workplace.

However, let us also not forget that, even if we decide that we need more scientists and engineers as a society, we do not cease to need linguists, philosophers, and historians. Even if there is a place for adaptation in what universities offer, surely it is crucial that we safeguard the possibility for people to pursue less well-paid and less popular vocational paths that are nonetheless crucial to society!

I have emphasized before the data indicating that majoring in the liberal arts has in fact been demonstrated time and again, historically and in the present day, to serve graduates well whether they go to work for Google or become lawyers or do anything else. But merely emphasizing that again, in addition to being repetitive, also risks giving the impression that we don’t need to change, adapt, grow, and sometimes shrink in response to changing times.

What are your thoughts on how higher ed needs to adapt to changing times – and on when and how it needs to persist defiantly in the face of attacks and criticisms?