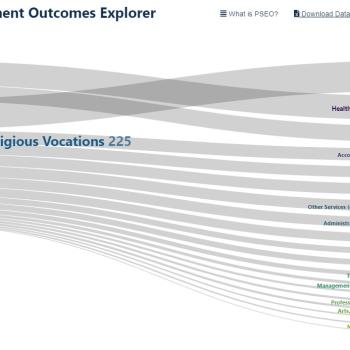

Most readers of this blog will know that in March I stepped into an administrative role as Faculty Director of the Core Curriculum at Butler University. Even before that time – but much more since – I have been giving a lot of thought to something that most faculty know, but many students seem not to. The core curriculum at institutions with a strong liberal arts focus is not something unrelated to one’s major and one’s reasons for being at university, but the heart of it. Many students attend Butler because the degree is prestigious, and yet never put two and two together so as to understand why it is held in such high esteem, and why our graduates fare so well when it comes to finding employment. It is precisely because we provide a combination of broadly applicable skills and broad education, and focused vocational skills. The core curriculum is where we put those things that are so important that we think all students need to study them, regardless of their major. You may never excel at them or prefer them to other things, but you should at least experience them. Treating them as a chore or as things to get out of the way reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what a university education offers.

At Butler University, we recently added a requirement to our core that will ensure that students engage with matters of social justice and diversity. (An article in the Indianapolis Business Journal recently highlighted efforts by IUPUI, another university here in Indianapolis, to ensure that teachers are prepared in relation to such topics). See too the winner of this year’s Liberal Arts Essay Competition at Butler University.

In a recent article about the value of education, Scotty Hendricks wrote:

Without a proper education in the humanities, where we learn how to understand people we may never meet, how to evaluate arguments and charged rhetoric, and imagine differing scenarios from those we see every day, we may be doomed to the fate of many a failed democracy before us.

Click through to read more from that article. Massimo Pigliucci also responded to claims that the humanities are indefensible. He writes:

I think that a defense of the humanities, right here and right now, is synonymous with a defense of the very idea of a liberal education. Which in turn is synonymous with a defense of the possibility and hope for a vibrant democracy. Or at least a democracy that doesn’t produce the sort of obscene politics and social policies that a number of Western countries, especially the US and UK, are currently producing. We can do better, we ought to do better, we will do better.

I’ve wondered about the need for greater integration of both information literacy and technological skills into university core curricula – on which see Matthew Lynch’s blog post on the need to train students to lead and not merely cope when it comes to digital literacies. See too the article about the need for balancing skepticism and trust so as to avoid falling into two possible pitfalls:

We need to teach how to trust as much as we need to teach fact-checking. We can’t simplify things by saying “it’s peer reviewed” or “it’s from a major national newspaper” or “it’s from a university press” or “that’s from a scholarly society, so it’s good.”

We also need to acknowledge that the skill of reading slowly and carefully has to be learned and practiced differently in an era of technologically-mediated skim reading as the norm.

A recent article proposes an intriguing combination of liberal arts education and guild-style apprenticeship in a vocation:

What I propose has the possibility of deflecting public criticism that a four-year liberal arts education is useless and has little to do with employment or practical application to the “real” world. Yes, you can talk extensively about the usefulness of a liberal arts education — admirably done yet again in the recently published book by Randall Stross, A Practical Education: Why Liberal Arts Majors Make Great Employees (Stanford University Press). Such arguments, however, have been presented to the public for centuries in America, and our pragmatic society seemingly will not accept, despite significant evidence to the contrary, that courses in philosophy, English, sociology and the like can help graduates obtain a first job out of college.

When economists and businesses say that liberal arts majors are “useless,” remember that they are thinking in terms of usefulness to themselves, i.e. their high turnover of low-paid expendable workers, and not the success and life satisfaction of the graduate.

Also on this topic see the AAC&U report on general education. One institution is seeking to trim its core in the hope that it will make them more attractive to students. Meanwhile, an op-ed recommends getting a liberal arts education, and then continuing to learn for the rest of one’s life (as Bill Gates and Warren Buffet do). Butler University’s Liz Freedman studies when and why students choose their majors (HT Kayla Arestivo). Other recent articles highlighted the disconnect between employer demands and student perceptions, especially when it comes to how well prepared students are. A survey of Google employees also had very important and interesting results:

Project Oxygen shocked everyone by concluding that, among the eight most important qualities of Google’s top employees, STEM expertise comes in dead last. The seven top characteristics of success at Google are all soft skills: being a good coach; communicating and listening well; possessing insights into others (including others different values and points of view); having empathy toward and being supportive of one’s colleagues; being a good critical thinker and problem solver; and being able to make connections across complex ideas.

Those traits sound more like what one gains as an English or theater major than as a programmer. Could it be that top Google employees were succeeding despite their technical training, not because of it? After bringing in anthropologists and ethnographers to dive even deeper into the data, the company enlarged its previous hiring practices to include humanities majors, artists, and even the MBAs that, initially, Brin and Page viewed with disdain.

When they have a chance to think through the best arguments from educators of the past, students buy into the idea of a liberal arts core more than we think they do…even to the point where half of them don’t think 15% is enough and are willing to go with greater than 50% to get more. And even to the point where half of the them would recommend an entirely required college curriculum over one where nothing was required.

All around the world (I discovered on a recent trip overseas) students complain about being asked to take courses outside of their major. We clearly have a lot of work to do in helping the general public and our present and future students understand that university education involves becoming broadly educated, well-rounded, and capable of being creative and making connections, with an aim to participating meaningfully in society in ways that are not limited to what one does at work.

Molly Worthen wrote in the New York Times recently:

Producing thoughtful, talented graduates is not a matter of focusing on market-ready skills. It’s about giving students an opportunity that most of them will never have again in their lives: the chance for serious exploration of complicated intellectual problems, the gift of time in an institution where curiosity and discovery are the source of meaning.

That’s how we produce the critical thinkers American employers want to hire. And there’s just no app for that.

Colleen Flaherty and Chad Wellmon wrote about core curriculum as a series of checkboxes (and how to get away from that). Research also suggests that education broadens students’ political perspectives, making it crucial to the functioning of a healthy democracy. And with that, having returned to a point made early in this post, I’ll end with a question. Did you study in an institution that emphasizes the importance of becoming broadly educated and not merely narrowly skilled? How has that benefited you since graduation, and what advice would you have for universities and their students in light of your own experience?