Bruce Gerencser recently wrote a blog post about the place of belief in Evangelicalism. While I often appreciate what Bruce writes, I must object to his characterization of faith as by definition meaning believing without evidence, and more specifically believing what the Bible says about people and events even when we have no corroborating evidence. That is, to be sure, one possible meaning of “faith,” and one that is particularly widespread in our time, especially among conservative Evangelicals, which is what Bruce used to be. But within the Bible, faith does not mean believing the Bible, nor even (for the most part) believing that things happened or that certain dogmas are correct. Faith is trust in God for things that are not yet seen because they lie in the future. And as Hebrews 11 makes abundantly clear, the element of trust in God is the key part, since the individuals listed also had faith or hope about things that would happen and which did not!

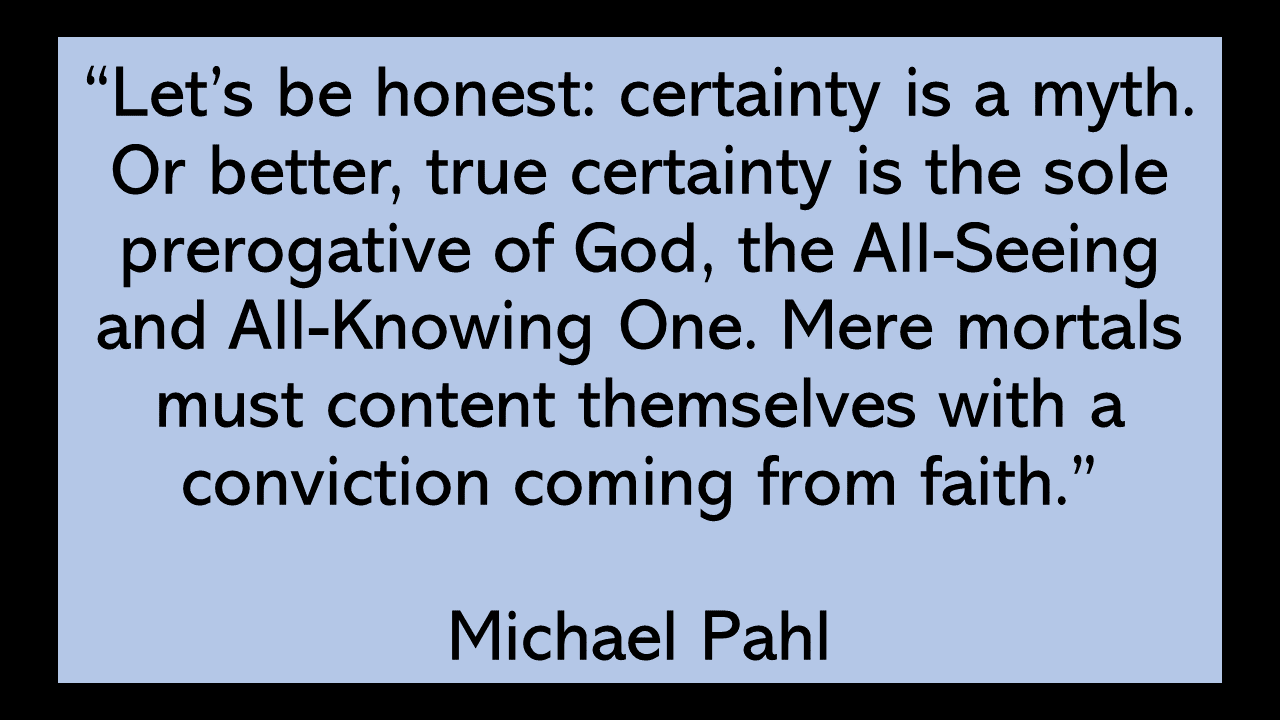

On this subject see also the recent post by Michael Pahl in which he wrote:

Let’s be honest: certainty is a myth. Or better, true certainty is the sole prerogative of God, the All-Seeing and All-Knowing One. Mere mortals must content themselves with a conviction coming from faith. While the fruits of human certainty and conviction can sometimes look the same, there is a subtle difference between the two, a subtle difference that makes a world of difference.

Certainty claims an unbroken connection with the divine perspective; it says, “I know because God knows.” Conviction acknowledges the fallibility and finiteness that mark our humanity; it says, “I know only in part, I see only through a dark glass.” Certainty says, “I have faith, which is as good as sight.” Conviction says, “I have faith, despite my lack of sight.” Certainty says, “There is no other way for anyone to explain the evidence.” Conviction says, “There is no other way for me to explain what I’ve experienced.” Certainty says, “I know and therefore everyone should act.” Conviction says, “I believe and therefore I act, and I act alongside others of similar conviction.” At its worst, certainty can lead to a knowledge that merely puffs itself up. At its best, conviction can lead to a love that builds others up.

It is this “conviction,” as I’ve called it, that characterizes authentic Christian faith—whether that of the “doubtless faithful” who seem to live free from difficult questions, or that of the “faithful doubters” haunted by these questions throughout their lives.

While the Church needs the “doubtless faithful,” it also needs its “faithful doubters.” They are the ones who are suspicious of well-worn human rituals and wary of the latest trends and fads; with guidance they can properly scrutinize these for adherence to genuinely Christian convictions. They are the ones who are unconvinced by simplistic answers to complex questions; with encouragement they may seek more nuanced solutions which are paradoxically both less and more satisfying. These “faithful doubters” may find themselves on the fringes of mainstream Christianity, at times even missing out on the full blessings of community life. But the Church needs people on the boundaries, engaging our culture with authentic questions and conversation while also calling the Church to an ever deeper and more authentic faith and life.