I was obviously aware of Jesus’ contrasts between himself and his disciples on the one hand, and various texts and persons of ancient Israel on the other. Yet somehow the words of Luke 9:55 never struck me quite as forcefully as they did in a recent conversation on this blog. The words have such significance that there were scribes who understandably felt the need to omit them.

A commenter here said that “Jesus never once denied God’s working as described in the Old Testament.”

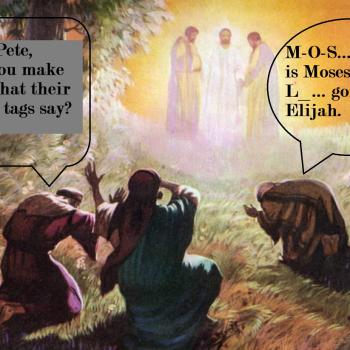

But what else can it mean if Jesus not only rebuked his disciples for wanting to do what Elijah had done, but said that they don’t know what manner of spirit is prompting and leading them if they are suggesting such a thing?

Some have suggested that, rather than searching for isolated sayings that are supposedly authentic, it is a better historical method – one that better reflects what we know about both human memory and the influence of historical figures – if we seek to triangulate from the various trajectories that emerge from an individual or movement. That would include those who further radicalized some aspects of what they said and did, and those who sought to domesticate those things that the others (over-)emphasized. In this case, trajectories that stretch out from Jesus include conservative law-observant Jewish Christianity, figures like Paul, and an embrace by Gnostics (or, in the view of some, the actual origins and development of Gnosticism). Perhaps sayings like this are crucial to our understanding of the historical figure of Jesus, and how he could have been claimed and the subject of controversy between such diverse groups as those who insisted that the God of Israel was the God and Father of Jesus and that God’s Law remained in effect for all his followers, and those who claimed that the Creator was an inferior or even malevolent figure whose Law and character were to be repudiated.

Of related interest, see Allan Bevere’s post on an important example from church history of affirming while denying the Jewish Scriptures/Old Testament, namely the decision of the Jerusalem Council to include Gentiles in the nascent Christian movement without requiring that they be circumcised. That’s a complicated issue, since the decision of the Jerusalem Council could be understood as according Gentile Christians the status of resident aliens, people who observe the laws of Noah that are for all righteous human beings, but who are not part of the covenant people. The very complexity of making sense of what Acts depicts having happened with respect to the Jerusalem Council, and of interpreting their decision, is broadly relevant to the topic we discussed here.