From Eboo Patel’s recent article in Inside Higher Education:

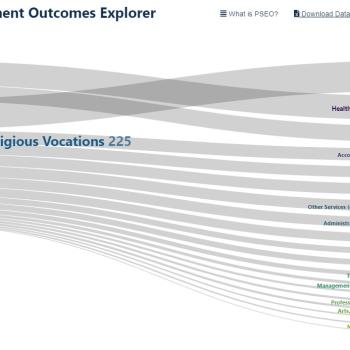

My larger point is this: in an era of higher ed where identity is king, diversity education often means unmooring some people from their identities while working hard to tether other people more deeply to theirs. The standard view appears to go like this: a white middle class Evangelical man ought to be unmoored from his identity, a working class black Muslim female ought to be more deeply anchored in hers.

But what of those values of liberal education that Tara Westover highlights? To see and experience more truths than one’s father told you – no matter what race or religion your father happens to be? To consider multiple perspectives – including ones that feel like they unmoor you? To construct one’s own mind and to self-create – apart from group identity?

Do we offer this pill to all or to some? Is it a privilege or a burden?

On the one hand, there is surely nothing inappropriate if an educational approach that aims at liberation of individuals and communities, the promotion of justice and combating oppression, has different impacts depending on a powerful majority than on the marginalized, on abusers of power than on their victims. But we often do not think specifically about how this relates to the religious and other cultural identities students bring with them. In one example Patel mentions, I would be equally happy whether a Mormon, an Evangelical, or a Rastafarian came to embrace modern medical treatment that they had been brought up to reject, especially if my doing so saved their life. I would be happy if each learned to appreciate the perspectives of others and insights from the critical study of the history and texts of their own religion, taking no particular delight in them either abandoning their tradition, remaining firmly in it in a conservative manner, or charting their own path along a tightrope seeking to balance tradition and new information.

I see my role as educator as providing students with resources and challenges that will serve them well as they make up their own minds about such matters. Believing that they should study their religious tradition and that of others using tools of academic scholarship, that they should question things they have been taught and assumptions they take for granted, are a value-laden stance. This is not something impartial and value-free. On the contrary, it is an application of the values underpinning liberal education to the subject of religion. I agree with Patel that religion is often neglected even at institutions that are profoundly interested in diversity and justice. I also agree that the result is often a profound inconsistency in academic cultures. However, I think that the challenges posed by our human intersectional identities are not insurmountable, as long as we make clear up front what values guide our educational endeavor. If we make clear that every student will have their assumptions challenged, and every student will be free to plot their own course personally while having to remain committed to respect and intellectual inquiry as part of the campus community, we will probably have fewer complaints when one student stops wearing a hijab and another starts. We may even feel less disappointment when only some students embrace mainstream science or renounce racism while in our classes, knowing that for some it will take longer for the full impact of what education offers to have its impact felt in their lives. We can allow them the autonomy to be who they are or become, while also insisting that, as part of the campus community, they will not express bigotry even if it remains rooted in their hearts and minds, and they will participate in learning mainstream science whatever opinions they may secretly hold.

It took me a while to recognize that I was doing a disservice to students if I claimed or tried to be “impartial.” In our era of “fake news” we need to be clear that not all claims to truth and knowledge are equal. But we must also be clear if we ultimately prioritize the freedom of students to be individuals and formulate their own views. We hope those views will be well-informed by mainstream expertise. We can certainly require that their education focus there. If we try to do more than that, to require assent to scholarly consensus as a creed, then however good and legitimate the tenets of that creed may be, I suspect that we will more likely produce hypocrites who pretend to “believe” what we insist they must, just as those who accept mainstream science must do at fundamentalist institutions of indoctrination. In the long term, we may have good reason to believe that students, and mainstream educational and academic work, are better served by an approach that balances providing information, explaining the reasons for the views we consider most worthy of credence, and respecting student autonomy and freedom with respect to crafting their own identity.

Of related interest, Inside Higher Education also highlighted a book about religion in American universities and colleges.