The moral resources needed to navigate the conflict between non-judgmental inclusion and social justice are things like community, confession, humility, truth-telling, forgiveness, reconciliation, patience, and peace-making. To name a few things. These are resources that help us pursue both non-judgmental inclusion and social justice at the same time. These are the moral resources that help hold the paradox together.

Christian progressives have access to these resources in a way secular progressives do not. For the most part, in my estimation, secular progressive morality, at least how it plays out on social media, lacks the moral imagination and resources required to navigate the contradiction at the heart of their vision of a moral world.

Secular progressives can be moral, no doubt about it. They just can’t be moral in a way that makes any sense.

I was all set to defend secular progressives, but I am not sure that Beck is wrong about this.

I do think it needs to be emphasized that the category of people who have the resources to navigate this tension is not “Christian progressives.” I say that because there are plenty of Christians who, at the very least, show that they have not availed themselves of such resources, engaging in mere party politics and tribalism. And I say it because there are humanists, agnostics, atheists, and others whose outlooks as well as actions show them to be “moral in a way that makes sense.”

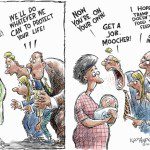

So in what sense, then, do I think Beck is right or at least has a point? My social media is filled with people whose progressivism looks like Trump-hatred and GOP-bashing rather than an effort to love and defend the victims of racist, sexist, and in other ways discriminatory individuals, whether they be elected officials and lawmakers or just ordinary citizens.

It takes a profoundly spiritual vision to value and defend the oppressed while never losing sight of the humanity of the oppressor, and never ceasing to make the aim their transformation and redemption rather than their destruction.

When I call it spiritual, I am using the term in a way that is entirely compatible with not only humanism but even atheism. “Spirit” has meant different things down the ages and means very different things to different people today. In an era when the idea that it is a separate substance from matter or flesh, connected to them via the pineal gland, language about spirit might simply be discarded. But we lose a lot if we do so. Spirit denotes those aspects of material existence that we value in a way that goes beyond the level of physical description or laboratory analysis. It is where personhood resides, even for a thoughtful materialist.

And it is the failure to cultivate those aspects of ourselves, and to recognize and value those aspects of our political, economic, and moral opponents, that is why I so often see secular progressives behaving in deeply disturbing ways on social media.

Particularly when I see fellow academics who are progressives engaging in expressions that appear to be mere enemy-hatred, I sometimes wonder if they shouldn’t know better. But I think Beck’s point suggests that the answer is no. The issue is not with what they know. It is with whom they value, and how, and why.

It is a spiritual act to value and love enemies. It is a difficult balancing act to actively side with and defend the victims of oppression while not losing sight of the humanity and value of their oppressors. Is Beck right that such an undertaking is by definition not the work of flesh and matter alone, but a work of spirit – however one might define that term?

Before concluding, let me quote a short bit of an article by Simran Jeet Singh, written in the wake of the mosque shooting in New Zealand:

Physical safety is something all parents think about, from rounding table corners when infants learn to walk to teaching young kids about stranger danger and looking both ways before crossing the street.

But how many of us truly think about how we want to protect our children from internalizing the disease of hate? What are we actually doing to preserve the loving innocence of our children so that they never fall prey to hateful ideologies?

Robert Talisse wrote on the subject of bipartisanship in politics:

The problem of polarization thus does not find its solution in measures by which we can enact better politics — the problem is politics itself. To be sure, the bipartisan civic ethos is an indispensable ingredient of a flourishing democracy. But it cannot be cultivated under conditions where everything we do is plausibly regarded an expression of our political loyalties. When politics is all we ever do together, our efforts to repair democracy by means of strategies for enacting better politics are doomed simply to backfire. What is required instead is the reclaiming of regions of social space for shared activities that are in no way political, occasions for cooperative endeavors in which the participants’ political affiliations are not merely suppressed or bracketed, but irrelevant and out of place. If you now find yourself wondering whether such collaborations could possibly exist, you have placed your finger firmly on the problem of polarization. For polarization has led not only to the colonization of our social environments by politics, it also has enabled politics to seize and confine our social imagination. That we must struggle to conceptualize avenues of social collaboration that are not structured around our political identities is the fullest manifestation of the problem of polarization. To frame the upshot somewhat paradoxically, if we want to repair our democracy, we need to focus our collective attention elsewhere.

Also related to this subject: Scot McKnight blogged twice about whether there can be a scientific basis for morality. And on the subject of not merely being divided along political divides, Red Letter Christians highlighted the importance of Howard Thurman in relation to this topic; the New York Times had an article on the subject as well; and there’s always more on Richard Beck’s blog.