I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to participate in the Inside Higher Ed 2019 Leadership Series workshop “The Future of Gen Ed 2019.” It was incredibly informative and at times downright inspiring. You can read Coleen Flaherty’s account of the event that inside Higher Ed published. What follows below is based on my own notes taken while in attendance.

The introductory session reminded us that Gen Ed is distinctive of US higher ed in comparison to others, especially the European model. For us, historically, being educated means more than just taking courses in one’s major. Originally universities were not inclusive institutions. Over time we have expanded access but held true to conviction that breadth as well as depth is important.

At the moment this tradition finds itself under attack. This is by no means the first time voices have suggested that we should narrow our focus to career preparation. Yet at the same time, there is substantial evidence that gen ed is valuable for the workplace.

Scott Jaschik of IHE said, “Gen Ed is not the same at every institution, and I think that’s a great thing.” He then proceeded to share the aggregated results from a survey of provosts. Here are some highlights:

- Less than one percent of provosts strongly disagree that gen ed is important. 93% agree or strongly agree.

- Responses to a question about whether students at their institution understand the purpose of gen ed cluster in the middle of the scale.

- There was a roughly even spread when asked if gen ed requirements have become too expansive.

- 22% of provosts strongly agree that faculty are enthusiastic to teach gen ed, that number dropping to 3% at public doctoral institutions. Faculty at R1 institutions may be inclined to think this is “important for somebody else to do.” Faculty pay attention to what is rewarded at their institutions.

The MLA recently had a session on reviving English major. One successful strategy was to make top professors teach in gen ed. Enrollments in major and all courses went up. Students notice these things. It matters who is teaching in the core. In one instance, a department chair assigned themselves an 8am teaching slot, which sent the message this is important.

There was a time when a chief academic officer would have been embarrassed to say they eliminated history or philosophy. The shame is gone. When Wheeling Jesuit eliminated every liberal arts major, the Jesuits called it out and said they can no longer call themselves a Jesuit institution. Wisconsin undid the cuts previously announced. There is some encouraging news. See for instance the IHE piece about Stevens Point. See too:

https://sententiaeantiquae.com/2019/04/15/reprioritizing-and-reallocating-tulsas-cuts-to-the-humanities/

More bullet point highlights:

- 29% of provosts say the number of majors in a given department is an appropriate way to determine which departments to cut.

- 90% believe that high quality undergraduate education requires healthy departments in fields such as English, history, and political science.

- 78% believe that colleges are prioritizing science, technology, and professional programs over those supporting general education.

By a show of hand, most of us present at this workshop I am writing about had not seen cuts impacting gen ed at our institutions, but it was acknowledged that we were a skewed sample. Nevertheless, it is heartening to know that so many exceptional colleges and universities are not at all headed in the same direction as those that have been making the news.

The next session was a panel: “General Education: Under Siege, but More Important Than Ever.” One panelist was Geoffrey Galt Harpham, the author of a book that was in our conference bags, What Do You Think Mr. Ramirez? It emerged from the story of a Cuban immigrant to the United States who got his GED, attended a community college that required a course on Shakespeare, and in it he was asked what he thought. It was the first time he had ever been asked that question. Harpham listened to the man’s story with interest when he met him, and took his business card without looking at it until later – at which point he discovered that the man in question was a professor emeritus of comparative literature! Harpham observed that there is no other country in the world in which this anecdote could have happened: no welcome for immigrants of the kind that the USA has at least aimed to offer historically, no high school equivalency, no community colleges, and no consideration of students’ opinions as pedagogically interesting.

Critics of higher education express concerns about high costs (Democrats), liberalism (Republicans), and not teaching 21st century skills (across the spectrum). The concerns should not be ignored, and one reason for some of the most common and widespread criticisms is a failure of universities and colleges, of faculty and administrators, to explain what we offer and why. The other panelist in this session, Lynn Pasquerella, told a story about her son who ended up working on the Jerry Springer Show. After having previously complained about gen ed requirements as a student, he called his mother to say that he finally understood why a course in small group communication had been deemed necessary. No one had told him, or at least no one had explained it to him clearly and persuasively – and if this was true for someone in a family in which the parents were a college president (Mt. Holyoake) and a professor, it is surely even more true for others.

High impact practices make a difference, but we need to connect curriculum to career if we want people to see this and understand it. Doing this can be grounded in equity of access to high impact experiences, especially if we understand ourselves to be educating for participation in democracy. John Adams observed a more purely vocational emphasis at colleges other than Harvard, and viewed them with contempt, as keeping people dumb and thus unable to fully participate in democracy.

It is critically important to learn to speak across differences in our increasingly polarized world, to deal with unscripted problems of the future. We need to engage students in real-world application of skills we are teaching them. As Lynn Pasquarella put it, everyone deserves the opportunity to find their best and most authentic selves through gen ed. To be given the opportunity to cultivate their capacity to write, speak, and think with compassion, conviction, and clarity. To think creatively, and understand and practice integration of skills. We need to explain how arts and humanities, and STEM, can and need to inform one another, and not only in one direction. A recent report emphasizing this took its title from a quote from Einstein: “Branches from the Same Tree.”

It is critically important to learn to speak across differences in our increasingly polarized world, to deal with unscripted problems of the future. We need to engage students in real-world application of skills we are teaching them. As Lynn Pasquarella put it, everyone deserves the opportunity to find their best and most authentic selves through gen ed. To be given the opportunity to cultivate their capacity to write, speak, and think with compassion, conviction, and clarity. To think creatively, and understand and practice integration of skills. We need to explain how arts and humanities, and STEM, can and need to inform one another, and not only in one direction. A recent report emphasizing this took its title from a quote from Einstein: “Branches from the Same Tree.”

One topic of discussion was whether foreign language should be part of gen ed. The answer should probably differ depending on context, or at least be flexible. It doesn’t make sense to require two years of language if many students are native speakers of a language other than English. What is needed is not a rigid requirement, but advising, so as to encourage dabbling (if not more) in languages other than the standard ones of Spanish and other European ones, especially in the case of students who already know English and Spanish. “Monolingualism is the worst form of American exceptionalism.”

Education is not just about how to be focused (as research faculty often are) but how to be flexible and adaptable. For this reason it is important for faculty to not just teach their specialty. There was some discussion of the use of introductory courses in disciplines for gen ed purposes, as opposed to courses specifically designed for non-majors. Often full-fledged gen ed courses more exciting because of their interdisciplinarity and their connection of a discipline with concrete issues of our time. Remember that we teach people rather than a subject. One example that was offered was a “Narrative and Moral Crisis” course. It places students in the midst of an experience of moral confusion and invites them to think their way out of it. Often students are not invited to express their depths in classes.

Access to liberal education is a major component at many community colleges, but there is a need for more partnerships between 4-year institutions and community colleges to foster still further strides in this area. Experiential learning can help bridge the divide that often exists between these two types of institutions. We are also prone to forget that the current predominant focus on research and creation of knowledge has not been there throughout the history of higher education. It is a result of the creation of the National Institute of Health and other such institutions, which saw the potential for universities to become hubs of research. Today, universities need to emphasize that our mission is educational, to shift away from a culture in which it is only research and knowledge-production that lead to prestige. The difficulty of quantifying good teaching is of course also a factor. But we have clearly failed to truly value in the tenure and promotion process efforts of faculty to be public intellectuals beyond the confines of the academy. What we measure matters. What wins a president at a public university favor in the state capitol matters.

During the Q&A a professor from Scotland offered a Scottish perspective. There, no grades count towards graduation before the 3rd year. It was suggested that the American GPA approach (and obsession) creates pressure, which results in resistance to gen ed. But what would it look like to effectively eliminate grades from the core? A very interesting Inside Higher Ed article recently offered a way to still do graded research, and yet break it down into manageable chunks that will be experienced differently by students. But beyond that, we should take seriously the fact that employers are relying on portfolios more than transcripts today. Could we move away from focusing on a GPA in the first year or two of university, if not indeed beyond, and focus instead on narrative descriptions?

Jim Henderson, President at the University of Louisiana, was once told “I don’t need more college grads, I need people who can code.” Jim asked if the man who said this whether he needs them to be critical thinkers, and the man said that’s what he needs most! There is clearly a disconnect between the perception at least some people have of what college education offers, and these skills employers are looking for. The journalistic skill that led to the most significant moment in this exchange should be noticed: the importance of asking follow-up questions! Many hospitals and doctors offices are aware that those who have studied humanities, social sciences, different cultures, and communication will be better nurses. Recent stories highlighting successful dropouts may not convey that these were dropouts from liberal arts programs who were able to do so and thrive precisely because of the approach to education they embraced early on. Most employers and employees understand, or at least can understand, the need for more than just training in the job title and narrow skills. Perhaps getting students to engage in more self-reflective activity will also help. An illustration of these points came in the form of the story of a president at Wachovia Bank, who went to the bank straight out of the army needing quantitative skills for that entry-level position. But then to become a manager he needed an understanding of the local community. As president he found himself thinking about philosophy. Without the whole curriculum that career path would have been blocked! In addition, as we often say, the jobs of the future haven’t been invented yet. The best preparation will make you flexible. Colleges need to be student-ready as well as students being college-ready (Lynn Pasquarella).

Should we tell students to trust us, we know what we’re doing, we were 18 once? Do we need to do more to advocate for reform at the high school level. High school is a crucial place to focus attention, without which we cannot improve higher ed. But colleges and faculty need to get involved in shaping high schools and not only calling for improvements to them. Pasquarella shared that her parents told her to go get a job instead of pursuing a PhD . They saw her path as an insult to them, separating herself, thinking herself better than them. There is a price in social and cultural capital that some students pay, which takes courage. As the Q&A continued there was mention of philosophy being taught at West Point. Servicemen need obedience but achieving higher ranks requires thinking of a non-rigid kind. Harpham shared that he taught an intensive seminar to Air Force faculty on Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Military academies take gen ed seriously.

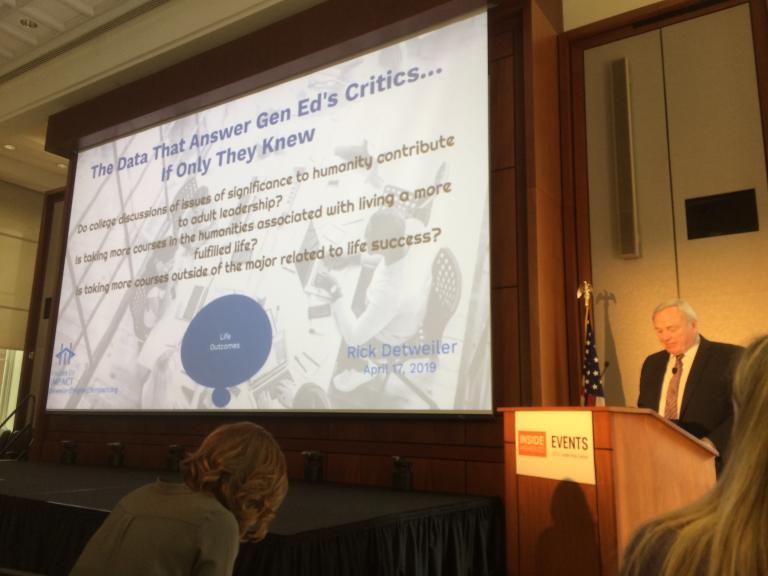

The session “The Data That Answer Gen Ed’s Critics… if Only They Knew” was presented by Richard “Rick” Detweiler. His main point was that there is quantifiable evidence that general education is good for you – not just your soul but also your bottom line. Economic and personal fulfillment measures confirm the value of gen ed. Detweiler acknowledged that parents and students are sometimes skeptical, and also acknowledged his role and that of other faculty in the overall situation: As a new faculty member in psychology, he understood his role and priority to be getting students to think like psychologists. He didn’t want gen ed to “get in the way of” the psychology curriculum. When his dean said he had to teach a freshman seminar, he was angry. This was at a liberal arts institution! With time, his views began to change. The world may need more psychologists, but it also needs people who think outside of narrow disciplinary frameworks. See the IHE article “My Limited Liberal Arts Education” for more on this topic. As Detweiler put it, “Study outside of one’s major leads to life success.”

The session “The Data That Answer Gen Ed’s Critics… if Only They Knew” was presented by Richard “Rick” Detweiler. His main point was that there is quantifiable evidence that general education is good for you – not just your soul but also your bottom line. Economic and personal fulfillment measures confirm the value of gen ed. Detweiler acknowledged that parents and students are sometimes skeptical, and also acknowledged his role and that of other faculty in the overall situation: As a new faculty member in psychology, he understood his role and priority to be getting students to think like psychologists. He didn’t want gen ed to “get in the way of” the psychology curriculum. When his dean said he had to teach a freshman seminar, he was angry. This was at a liberal arts institution! With time, his views began to change. The world may need more psychologists, but it also needs people who think outside of narrow disciplinary frameworks. See the IHE article “My Limited Liberal Arts Education” for more on this topic. As Detweiler put it, “Study outside of one’s major leads to life success.”

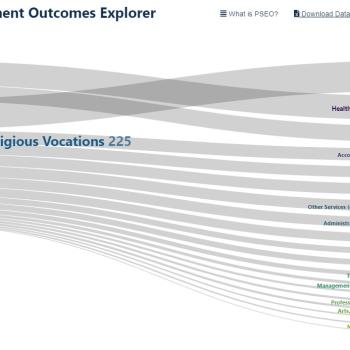

Assessment of the impact of a core curriculum/liberal education while students are still in school or recent graduates can certainly be useful. But we also need longer-term data, as well as more quantitative and concrete data to supplement the opinion surveys we tend to focus on. Detweiler did a study involving a national sample of 1000 college graduates from a range of different kinds of institutions. The interviews focused on those who graduated 10-40 years previously. The questions asked were not about opinions, “what do you think, how do you feel,” but were instead about their behavior while in college, and what they were doing now. How many courses did you take outside of your major? In adulthood, have you been named or elected to a leadership position in a community organization? Detweiler then understook statistical analysis to see if there is a demonstrable correlation.

There are, in specific life outcomes: continued learning, cultural involvement, life fulfillment, leadership, and personal success. These areas that Detweiler focused on are drawn from the mission statements of educational institutions. He asked questions about behaviors in the present such as: What do you read? How often do you visit art museums? Do you discuss things with other people? Do people come to you for advice about things outside your area of expertise? Do you mentor people? He also asked about their position at work and earnings (and was surprised people answered that!). He also asked questions related to general education: Did you take courses outside of your major? In the humanities? Did you have discussions with people of different values, culture, politics, and/or religion? Did you engage in discussion of philosophical/ethical/literary perspectives in most classes? Did you have your own views tested? Did you wrestle with questions to which no clear right answer? Did you write papers?

Among the things that I thought were particularly noteworthy was the fact that engaging with issues of justice and diversity, and broad education, both lead to higher income! Another was that, while the first job for those with a specialized professional degree often paid them a higher salary, that income disparity was not there 10 years out from graduation or more out, and sometimes had been inverted! People who are leaders and feel fulfilled were typically among the broadly educated, while there was no correlation between these experiences and any sort of technical or professional focus.

Not every general education component impacts everything, according to the data. That is an important results, since if everything seems to affect everything, nothing is clearly making a distinctive difference, and so the correlations are less informative and meaningful. This study is important if for no other reason than that it means the case for higher education can be made in ways that should be compelling to critics across the political spectrum.

The session also highlighted a need to shift away from a focus on what courses we require in gen ed. We should instead start back one step with educational practices, and then do research that documents and justifies the impact of what we do at our own institutions. It is not necessary to focus on all outcomes. Which ones fit our institution, its mission, and its students?

During the Q&A, someone from the Teagle Foundation asked how many students surveyed pursued this, and how many were required to do so and were perhaps surprised by the impact? In other words, can we also study whether required core makes a significant difference, or whether the largest benefits are reaped by those who are intellectually curious and pursue this kind of broad educational experience. But in some ways that question is less important, since making the case for the value of this kind of education should lead to more students pursuing this type of educational experience willingly, if not indeed eagerly. It is also important to note that not everyone in the study did all the things mentioned. The sample was constructed to vary the kinds of respondents, making for more interesting and robust data. But there are still broad statements that can be made which are quite powerful: Taking fewer humanities courses leads to a less fulfilled life. Taking fewer courses outside your major makes you less successful in the long term.

Since the audience was a group of faculty, there were obviously questions about the methods and their validity, and a desire to see the data supporting these claims. If I get hold of that, I will be sure to direct readers of the blog as to where to find it!

Given how long this recap is up until this point, I will continue with more about the event in a future post. Stay tuned!