Future: Telling the old old story ten thousand years from now

Science fiction sometimes depicts Christianity as it might become in the future, as well as futures in which there seems to be little or no place for it or memory of it. Such stories provide a helpful counterbalance to the tendency to treat our own time and perspective as normative. In every Christian denomination, someone at some point has drawn up a timeline of church history, typically reaching its zenith in their own denomination. If we imagine that the future from then on will simply preserve this purported perfection with no need for or experience of further change, we are clearly fooling ourselves. But we sometimes do indeed manage to fool ourselves, which is why it is a useful exercise to draw the timeline further, to imagine the future as it might be, whether in utopian, dystopian, or realist fashion.

The Expanse incorporated the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints into its story for a very pragmatic reason: the storytellers needed there to be a very large spaceship of a sort that could be used to take a sizeable population to another world. Asking who could realistically be expected to build such a thing, human governments with their focus on immediate problems and reelection quickly excluded themselves as serious contenders. The LDS Church, on the other hand, could be imagined in the future to have both the funds to undertake such an endeavor, and a theological framework that might lead them to actually do so. Sometimes a particular type of religious figure or theological concept is just what is needed to tell a particular story or accomplish a particular future. [click SLIDE]

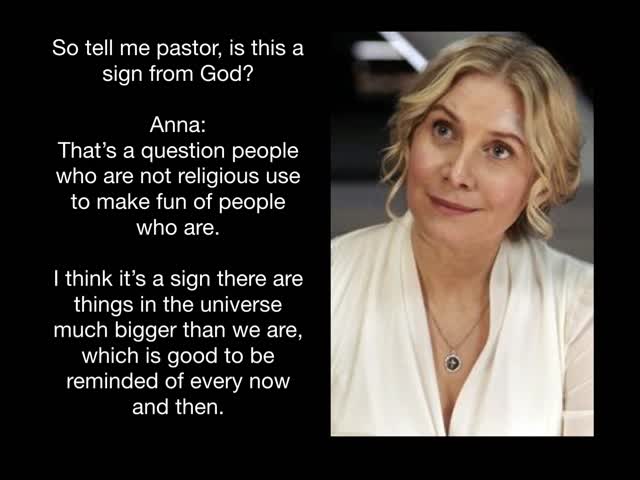

The Expanse also provides a good example of the depiction of a Christian clergyperson in a manner that is futuristic yet directly related to current trajectories. Rev. Anna Volovodov is both sympathetic and fallible. In other words, she is portrayed as genuinely and realistically human in a way that clergy in fiction aren’t always.

Anna is a Methodist, representing the Christian liberal mainline in her activism for matters of socioeconomic justice, her peacemaking concerns, and her marriage. Since there is no one Methodist church these characteristics are entirely plausible even today, never mind a few centuries from now. (I avoided saying “united Methodist” since capitalized that is the title of one of the many Methodist denominations). Anna offers good responses to those who mock her faith, and avoids offering pat answers to questions. Yet in one instance, in the very act of doing that, she fails to offer comfort to a fellow Methodist who is experiencing a crisis. She is human, well-rounded, and a fine counterexample to the notion that the future of Christianity is just something to be pessimistic about, or that clergy will be universally lined up to speak against anything groundbreaking whether ecclesiastical or in the realm of space exploration. She approaches the crossing of a new frontier with awe.

Star Trek’s Starfleet is often viewed as a depiction of a secular future, and it is that in the actual meaning of the term, but not necessarily in the pejorative sense in which it is sometimes misunderstood. We get the impression that crewmembers such as Lt. Uhura and Dr. McCoy have some personal religion of one sort or another, most likely Christian. The absence of a chaplain on the Enterprise is noteworthy but ultimately unsurprising. If we assume that Starfleet genuinely represents human diversity, and at least some non-human diversity, how many chaplains might be needed aboard the Enterprise to serve their needs? Chekhov might need a Russian Orthodox chaplain, Scotty one from the Church of Scotland (perhaps any Presbyterian might do), there are bound to be atheists and secular humanists on board, and on and on the list would go. If the lone Vulcan’s needs are not catered to is that discrimination? If you can get counseling via subspace and at some starbases is that adequate?

(Babylon 5 featured a famous scene in which, in order to introduce the representatives of various non-human religions and cultures to a representative of human religion and culture, a long line is formed with many people in it).

Faced with the impossibility of catering fairly to everyone’s needs on a starship, Starfleet would not need to be anti-religious to refrain from providing chaplains on board.

I spoke once at a seminary about this topic, discussing the absence of a chaplain on the Enterprise in the original series. We observed that there is a chaplain of sorts on the Enterprise-D in The Next Generation, in the form of Guinan. That the closest the ship has to a chaplain is at least formally the bartender is worth reflecting on.

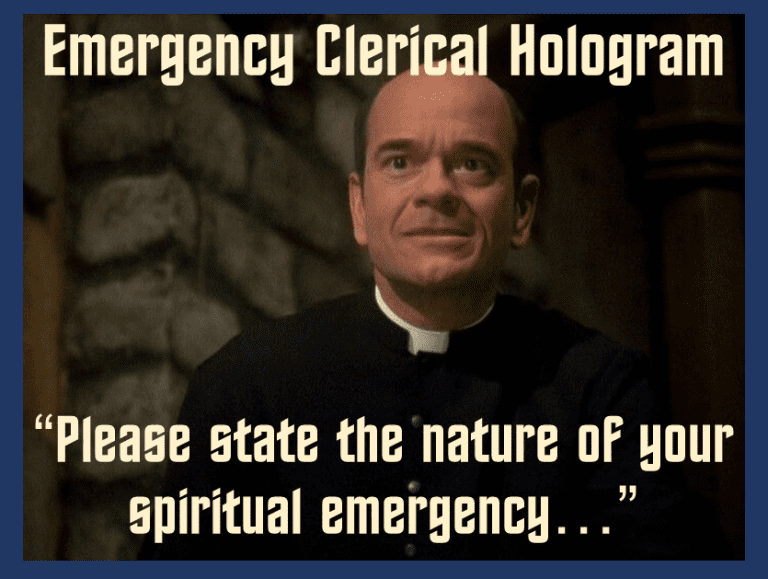

Voyager provided a technology that could potentially address this issue, and which might be useful in hospitals and other contexts on Earth if it could ever be developed. The Emergency Medical Hologram that provides medical advice and treatment in the absence of a qualified organic life form raises the question of whether we could envisage an Emergency Clerical Hologram. The program could provide an AI human-like interface that was made to look appropriate to the religious tradition of the individual seeking assistance. Presumably when it appeared it would ask, much as the medical hologram did, “Please state the nature of your spiritual emergency.”

It is absolutely appropriate to ask about the usefulness of technology of this sort in the near and not merely the distant future. It will never be the case that every hospital, school, or for that matter town will have a resident member of every type of clergyperson that individuals in that community might desire to speak to in moments of hardship and difficulty. Even if we agree that an AI hologram is not ideal as a source of comfort and support for the human soul, is it better than nothing? Conjuring one up with a few taps on a screen certainly would be convenient, whatever the shortcomings of the service provided.

Frank Herbert’s Dune novels imagine the future of Bibles as well as religion(s). Herbert imagined a distant future in which a number of traditions had consolidated both their identity and their scriptures. Even so, some had preserved ancient traditions in secret, although we do not learn just how faithfully or accurately they managed to do so. Dan Simmons’ Hyperion Cantos envisages a church transformed by the discovery of a cross-shaped organism, called the cruciform, that reconstitutes the person if they die, rendering them practically immortal. Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow and Children of God, and more recently Michel Faber’s The Book of Strange New Things, envisage a future in which clergy are involved in spacefaring, contact with intelligent living things on other planets, and in the process wrestle with the terrestrial faith they had beforehand and what it means in relation to such experiences. But even for humanity without direct contact with intelligent life elsewhere, what will it be like if people try to keep singing “O Little Town of Bethlehem” not merely on the other side of the planet but the other side of the galaxy? Can we envisage people singing “on a hill far away, stood an old rugged cross,” when the distance represented by “far away” is measured not in miles but in light years?

Christianity has been entangled with empire both officially and unofficially over the history of what we call Christendom. There are similarities between religions and empires or civilizations even when considered separately. Thus things that we learn about empires are relevant to our consideration of Christianity in science fiction. As has already been mentioned, Star Trek imagined a Roman Empire that never fell. There has as yet never been an empire that has persisted on Earth for so many millennia. The scenario makes for a useful thought experiment, however implausible. The real lack of imagination, however, is in the fact that the Roman Empire was depicted as so similar to its ancient precursor despite the massive changes in technology. If it is difficult to imagine a civilization enduring for so long, it is even more difficult to envisage it achieving the kind of equilibrium that would allow its major cultural components to remain unchanged. The same is true of religion in general and Christianity in particular. The idea that the people of New New York (in fact, the 15th New York) in the year 5 billion 29 will still be singing the hymn Abide With Me makes for a very moving scene, but it defies any hint of plausibility—not that Doctor Who tends to worry about that, of course. The inclusion of hymns in the Doctor Who episode “Gridlock” was intended to critique faith, as something that led people to accept things as they were and not question. Yet when the people sing in response to the end of the multi-year traffic jam that serves as a major focus in the episode, it moves the Doctor to share things about himself that he hadn’t before. Russell T. Davies was focused on the critique of faith as fostering complacency. He ended up depicting it as also providing an outlet for rejoicing in community. It can of course at times be both, and at times neither.

There are countless other examples of Christianity in Doctor Who episodes set in the past, the present, and the distant future. We get to see the Massacre of St. Bartholemew Square in the past, a minister who is vulnerable to haemovores (i.e. sci-fi vampires) because he has lost his faith in human goodness (in “The Curse of Fenric”), and Anglican Marines which are a military body very different from what we see in the present day (in “A Good Man Goes to War”). We have already seen that Doctor Who is just one currently popular and ongoing franchise that itself represents but a small sliver of what sci-fi can bring to bear in expressing Christian faith or critiquing it. One can time travel to the past to see Jesus or become him. One can imagine an unspecified time in the future—it could be later today—in which Jesus returns, having been gone for so long because after he levitated into the sky, he encountered an alien ship which carried him away, delaying things considerably. In case you think I’m kidding or speaking hypothetically, that’s the delightful and genuinely interesting scenario featured in the story “Jesus Christ, Reanimator” by Ken MacLeod.

Some of the questions these kinds of stories raise may seem far-fetched. They remain hypothetical at least for the time being. It is not, however, a given that that will always be the case, and if we do encounter extraterrestrial intelligent life at some point in the future, we will probably do so in better and more constructive ways if we have thought seriously about them in advance. Vatican astronomer Br. Guy Consolmagno has written a book that provides his answer to questions such as Would You Baptize and Extraterrestrial?

If aliens arrive tomorrow, only those who have already been thinking about the matter will be well poised to offer a substantive serious suggestion for how to respond. That is true not just of theologians but of the military and the world’s political leaders. The point of hypothetical scenarios and thought experiments is to help us prepare for when the unimaginable happens, as well as for more mundane happenings.

The conclusion of the public lecture will follow next time…

The Past, Present, and Future of Christianity in Science Fiction Part Two: Present