It has been a while since my last entry in this series on Keith Ward’s book The Big Questions in Science and Religion. Chapter 8 looks at attempts to explain morality, and religious beliefs, in evolutionary terms. His short answer is that, unless one accepts a purely reductionistic approach, then we cannot. We may be able to explain certain instincts and inclinations in evolutionary terms, but as long as we have some notion of free will, then evolutionary biology will not be able to guide us as to what we should do (p.202). When Ward asks whether the usefulness of altruism for survival among our ancestors in the distant past is adequate justification for the practice of altruism in the present, he answers as follows: “It is not, any more than it is a reason for swimming now that our first ancestors were probably rather like tadpoles. It is always interesting to know how we evolved, what our imprinted behavior patterns are, and why they are the way they are. But if we can choose which inclinations to follow, we need some other reason for our choices” (p.203). As he puts it elsewhere, “we need to have reasons, not just causes, for our responsible actions” (p.205).

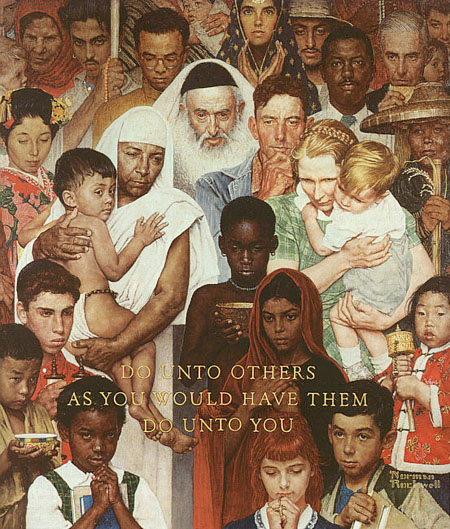

Here’s a great quote from this chapter: “Religion, like morality itself, can be used to bolster sets of values that are oppressive to many – the systematic subjugation of women throughout recorded history is often justified by appeal to “moral” values of family and sexual modesty. What is needed is not more morality but more of a sort of morality that takes the flourishing of all beings seriously and that opposes violence and oppression. Similarly, we do not need more religion but more of a sort of religion that reinforces compassion for all beings and nonviolence” (p.196).

Here’s a great quote from this chapter: “Religion, like morality itself, can be used to bolster sets of values that are oppressive to many – the systematic subjugation of women throughout recorded history is often justified by appeal to “moral” values of family and sexual modesty. What is needed is not more morality but more of a sort of morality that takes the flourishing of all beings seriously and that opposes violence and oppression. Similarly, we do not need more religion but more of a sort of religion that reinforces compassion for all beings and nonviolence” (p.196).

Ward also discusses religious experiences, and notes that about half of human beings have them in one form or another, placing before us the dilemma that both halves regularly regard the other half as deluded for claiming to have had, or failing to have had, such an experience (pp.211-213).

Ultimately, it doesn’t seem that biology, or even religion, can provide adequate justification for our morality. While Ward is willing to give a certain weight to the notion of a benevolent Creator as a source of morality, I’ve suggested before that even the existence of God cannot turn the morals of the deity from an “is” (the morals an eternal God simply happens to have) into an “ought”. And perhaps this is just as well. Nothing can turn the decision to consider others and value others into a mere evaluation of fact. Ultimately, it is a personal decision, not about whether we will discover the will of God, but about whether we will turn from self-centeredness to concern and compassion for others, if for no other reason than that we hope that others will do the same for us, who are “others” from their perspective.