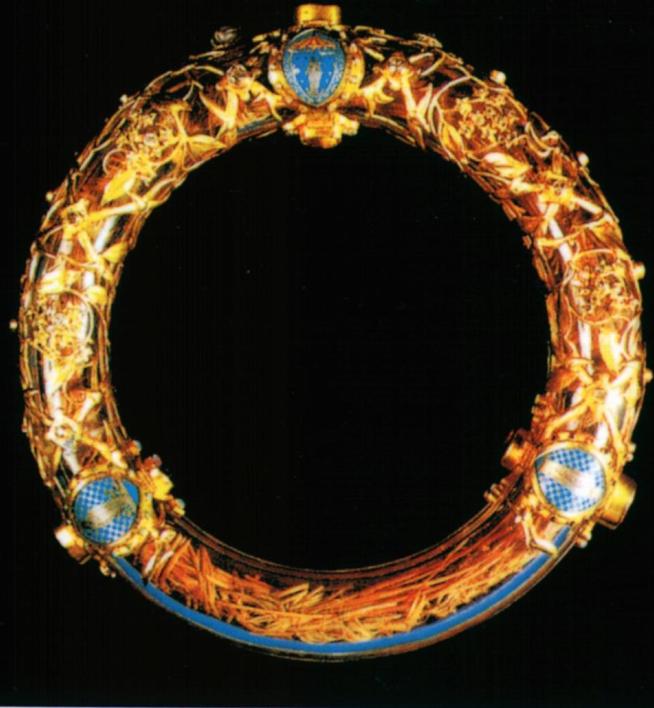

Français : La Couronne d’Épines dans le reliquaire circulaire en cristal de 1896. Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris.

Gavigan 2007 non_restricted GFDL 2007

THE QUESTIONS:

About the Crown of Thorns rescued from the Notre Dame Cathedral fire in Paris: Is this the actual crown that Jesus Christ wore at the Crucifixion? Does authenticity matter? What’s the role of such relics?

THE RELIGION GUY’S ANSWER:

Before Jesus Christ was crucified, the New Testament records, Roman soldiers “stripped him, and put a scarlet robe upon him, and plaiting a crown of thorns they put it on his head, and put a reed in his right hand. And kneeling before him they mocked him, saying, ‘Hail, King of the Jews!’” (Matthew 27:28-9, similarly in Mark 15:17 and John 19:2-3).

More than 19 centuries later, a relic believed to be that humiliating crown was rescued from the disastrous fire at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. It is the most revered item in the cathedral’s collection, which also contains what are identified as one of the nails that pinned Jesus to the cross, and a wooden fragment from the cross itself.

In today’s supposedly secularized France, only 41.6 percent of citizens are baptized Catholics and a mere 12 percent tell pollsters they regularly attend Mass, well below numbers elsewhere in Europe. Yet the damage and substantial survival of the venerable cathedral, and the valiant effort that saved its treasured relics, roused fervent sentiment nationwide.

Is the celebrated Crown of Thorns, which goes on public display each Good Friday, authentic? There’s no way to prove it is, nor do the Bible or early Christian annals say the artifact was preserved. Here’s what we do know, courtesy of British historian Emily Guerry, writing for theconversation.com.

The earliest record dates from four centuries after the Crucifixion, when St. Paulinus instructed Christians to venerate a “holy thorns” relic at the Mount Zion basilica in Jerusalem. In A.D. 591, Gregory of Tours wrote the first surviving description, saying the crown “appears as if it is alive,” with leaves said to wither and then turn green again.

Little is known between A.D. 637, when Muslim conquest limited Christians’ access to Jerusalem, and the mid-10th Century, when the crown somehow turned up in the Byzantine emperor’s collection in Constantinople (today’s Istanbul). France’s King Louis IX later gained ownership of the relic by helping pay off an imperial debt, and the Crown was welcomed to Paris with a grand street procession in 1239. The crown was eventually to survive France’s anti-religious revolution, relocations, two world wars, other tumult, and now a furious fire.

The veneration of relics from Jesus and the saints by today’s Catholic and Orthodox believers perpetuates a very early tradition. The first known example occurred in A.D. 156 when devotees acquired the bones of St. Polycarp after he was burned at the stake, and placed them in a shrine where his martyrdom date was commemorated. By the 4th Century, such devotions had become widespread, energized in part by the reported discovery of the True Cross by St. Helena, the mother of the Emperor Constantine. In A.D. 787 the second ecumenical council at Nicaea declared the presence of relics to be essential when a church was consecrated.

The Middle Ages brought a busy market in greatly valued relics, including several other purported Crowns of Thorns, Veronica’s Veil that was thought to wipe sweat from Jesus’ brow, the Holy Grail (the wine chalice Jesus used at the Last Supper), and even the umbilical cord from Jesus’ birth and the foreskin from his circumcision, along with a profusion of holy nails and True Cross fragments.

From early on, the Protestant Reformation rejected veneration of relics. The Martin Luther biography by Lyndal Roper of Oxford University recounts some remarkable history. The young university in Wittenberg where Luther taught Bible, and the town’s over-all economy, benefited from the pilgrims who visited one of Europe’s most spectacular relic collections to receive remission of time in Purgatory through church indulgences.

The region’s ruler, Frederick the Elector, had amassed – yes – a purported thorn from Jesus’ crown, 19,013 bone fragments from saints’ remains, and the complete corpse of a child Herod slaughtered in Bethlehem when Jesus was born. Frederick’s territory banned sale of the papal indulgences that competed with its own relic trade.

Luther bit the hand that was feeding him, scorning “relics like the nails and the wood of the cross – they are the greatest lies.” His contemporary, the Dutch philosopher Erasmus, remained Catholic but famously quipped regarding relics of the cross that “if all the fragments were collected together they would appear to form a fair cargo for a merchant ship.” Despite Luther’s scorn toward Frederick’s relics, the Elector protected the Reformer for many years against the Holy Roman Empire’s death sentence.

Official Catholic policy on the veneration of sacred relics, still in place, was thence defined by the Council of Trent (1545-1563), whose reforms responded to the Protestant rebellion. The Council reaffirmed veneration as an aid to religious devotion, condemned opponents of the practice, denounced the sale of relics and associated superstitions, and urged caution on attributing miracles to relic devotionals. The council’s catechism spelled out biblical and theological support for veneration.

Orthodox Archpriest Vasily Demidov explained in a 1950 book that saints and their relics are never to be rendered worship. Rather, the church worships the One God alone, while “believing that the holy relics are divinely-chosen instruments of the power of God.”

Catholicism has an elaborate and well-known procedure for proving miracles of healing from prayers to the saints. The situation is quite different with relics. According to the 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia, the church has never “pronounced that any particular relic” is actually authentic, but “approves of honor being paid to those relics which with reasonable probability are believed to be genuine.”

Today’s most celebrated relic is probably Italy’s mysterious Shroud of Turin, which is thought to be the Savior’s burial cloth. The Shroud story is too complex to treat here, but you’ll find detail on that authenticity debate in this 2017 Q & A article: www.patheos.com/blogs/religionqanda/2017/04/shroud-turin-jesus-actual-burial-cloth.