THE RELIGION GUY’S ANSWER:

That seems highly unlikely at the moment, but it’s certainly intriguing to suppose that the faith might eventually deal with modern exigencies through dramatic change equivalent to, let’s say, Europe’s 16th Century Protestant Reformation.

The implications would be enormous, considering that this powerful faith has just reached a global total of 2 billion followers, compared with 2.6 billion for Christianity (by latest count from the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.)

Surprising possibilities are suggested by the newly published and essential “The Battle for the Soul of Islam: Defining the Muslim Faith in the 21st Century” (Palgrave Macmillan) by James M. Dorsey. This veteran journalist is an independent-minded specialist on the Islamic world at the international studies school of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, and “Turbulent World” columnist on Substack.

No alternative to religion

Dorsey asserts that “simply put, there is no alternative to religion as a moral and ethical yardstick for societies and systems of government,” much as modern secularists might yearn for some option.

The mind reels with this book’s vast (and alas poorly edited) array of current religious and political power-brokers, scholarly writings and speeches, international conferences and earnest declarations. Dorsey’s scenario runs as follows.

World Islam in this generation is greatly destabilized by feuds, wars, political upheavals, and terrorism claimed to be in the cause of and the name of God. Alongside the daily news diet, there’s sweeping and far less-noticed international competition to control and define Islam as a religious civilization. Since religion and politics are intertwined, rival nations have worked and spent lavishly to exert their “religious soft power.”

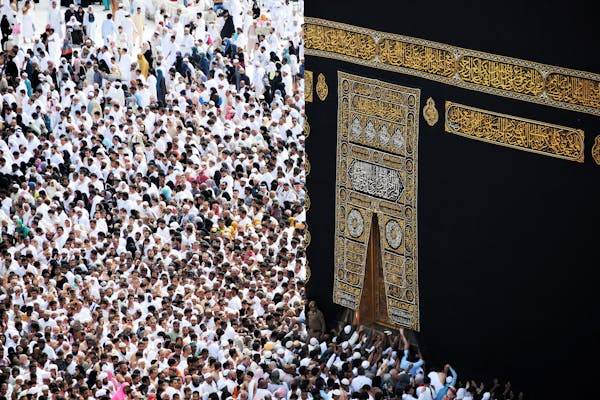

One major player, oil-rich Saudi Arabia, can claim unique stature as the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad, of his Quran, and thus of Islam. Saudi influence is further cemented by the mandate that if possible each Muslim must make at least one Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. The Saudis long spread Wahhabism, their rigidly austere form of the faith.

Omission with Saudi reforms

The de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (“MBS”) has lately instituted such reforms as allowing women to drive and to socialize without male guardians, curbing the religious police who monitor daily conduct, allowing public cinemas and musical concerts, and limiting global Wahhabi evangelism. But there’s also religious sanction for brutal dictatorship, and Jews and Christians are forbidden to erect buildings or hold public worship.

United Arab Emirates (UAE), a federation of oil-based fiefdoms formed in 1971, is ruled by President Mohamed bin Zayed. In contrast with its Saudi neighbors, UAE presents a noteworthy vision of toleration toward factions within Islam and non-Muslim religions. The policy was underscored in 2019 by hosting the first papal visit to the Arabian Peninsula as Pope Francis attended an historic interfaith conference. But such outreach is combined with Saudi-style authoritarian rule.

Turkey had an unusual role historically as the seat of the Caliphate, which nominally controlled most of the Muslim world for centuries but was abolished in Ataturk’s 1924 secularization. Since 2003, prime minister and then President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has gradually become less democratic and more insistently Islamic, and more ambitious in global religious networking.

One symbol: Ataturk made a museum out of Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia, a revered 6th Century Christian church that Muslims had turned into a mosque. Under Erdogan, in 2020 it became a mosque once again. Also, Turkey has shut the nation’s Orthodox Christian seminary for 53 years.

Iran as influential oddity

Iran is an Islamic oddity as the one major nation dominated by the minority Shi’a branch rather than the Sunni majority. Since its 1979 revolution, Iran has exemplified a system of rigid theocratic rule by clergy, with an expansionist version of Islam currently working out with international terrorism and fervent hatred toward Jews and Israel.

Other players include Egypt, with its huge population and 1,054-year-old Al-Azhar University, the most important of the campuses that are vying for influence within Islam. Qatar has been an important meeting ground for Islamic factions and outsiders, as right now with the Gaza conflict. And since 1996, Arabic and English broadcasting on its government-aided Al Jazeera TV has wielded sizable impact.

But Dorsey indicates that if there’s ever a reformation within Islam, Indonesia is the most likely place to begin. The nation’s importance is often neglected in the West but this huge democracy is the world’s largest Muslim nation, with 243 million believers according to the World Population Review. It’s also the world’s most devout population at 98% religious, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

Dorsey puts a bright spotlight on Nahdlatul Ulama (or NU, a name meaning “revival of the scholars”), by far the world’s largest Muslim civil society movement. He reports that its empire encompasses 90 million followers, a militia with 5 million troops, and then a massive body of Islamic scholars at its 27 universities and 18,000 seminaries.

And now, “humanitarian Islam”

This movement, increasingly assertive internationally, champions so-called “humanitarian Islam,” which insists that Islam is compatible with modern democracy, religious tolerance and pluralism, and the principles of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (The Saudi-backed Organization of the Islamic Cooperation, with 57 supporting nations, upholds the oft-violated 1990 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam.)

In the current ideological competition, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and their allied religious and political forces, style themselves as “moderate” foes of radical and violent political Islam. That contrasts with the Indonesians’ version of moderation, which promotes an ambitious reform of how Islamic religion is interpreted, embraces democracy and denies religious legitimacy to Mideast autocracies.

NU has its own political party and adherents have filled important government posts, including the presidency. But as a matter of history, Indonesia’s democracy is not deeply rooted. On April 24, the nation’s electoral commission rejected fraud complaints and declared Prabowo Subianto as the new president. Dorsey is wary because the new leader had “hardline Islamist supporters” in the past and holds “an at best illiberal view of democracy” that could clash with NU’s concept of religion, state, and society.

Unavoidable textual complexities

Dorsey does not delve into the complexities of what it will take to bring a religious reformation with modern understandings of righteousness in politics and human rights, including for women. In the Religion Guy’s view, any approach that seeks to undercut the authority of the Quran will fail.

However, faithful interpretation of Scripture is a different matter. Is a particular divine command given for all time or did it apply only in a particular ancient context? Did later revelations abrogate earlier ones, and which came first? The same questions arise with the Sunnah, traditions about the deeds and words of the Prophet in varied Hadith collections. The third layer of tradition is a massive fiqh (jurisprudence) body of rulings across centuries that applied those traditions but may not pertain to 21st Century circumstances.

If change is to occur, this textual scholarship is where the real work will be done, along lines of the experts cited in Dorsey’s copious footnotes.