The other night Rita and I were discussing a passage from the Bhagavad Gita on sacrifice. My wife was raised in the Roman Catholic faith, attended Catholic schools, and still attends their services on occasion. She was confused at first on hearing the passage, because the Vedic view of sacrifice differs so greatly from what she had been taught is sacrifice. For her, sacrifice is about depriving yourself of something you enjoy, or doing something extra like saying additional prayers, novenas, or attending additional masses, and the purpose of this kind of sacrifice is to make yourself worthy so that God will either forgive some past offense or grant a wish in the future . Sacrifice, for my Catholic wife, concerns sin and penance. Her explanation is as alien to my thoughts on sacrifice as the Vedic perspective was to her.

The Vedic view of sacrifice is about maintaining balance in the greater Universe, restoring the divine to the Primordial Creator Prajapati so that He may continuously create the World anew. Vishnu tells Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita

“When creating living beings and sacrifice, Prajapati, the primordial creator, said: ‘By sacrifice will you procreate! . . . Foster the Gods with this, and may They foster you; by enriching one another you will achieve a higher good. Enriched by sacrifice, the Gods will give you the delights you desire; he is a thief who enjoys Their gifts without giving to Them in return. Good men eating the remnants of sacrifices are free of guilt, but evil men who cook for themselves alone eat the food of sin. Creatures depend on food, food comes from rain, rain depends on sacrifice, and sacrifice comes from action. . . .the ever pervading infinite spirit is present in rites of sacrifice.”

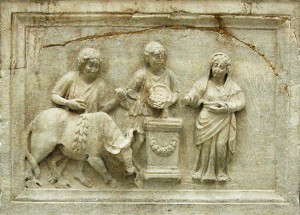

In Vedic tradition the performance of sacrifice takes on a cosmic imperative. It is vital to the continuation of the universe, since through the destruction of the material offering, body is returned to the material universe, the soul or genius of a thing is redeemed into the World Soul, and the spiritual essence is likewise returned to its spiritual origin. Through sacrifice the Primordial Creator Prajapat is regenerated so that He may constantly generate all things in the flow of the divine. In this way too, the cycle of life from birth to death into rebirth is maintained for all animate and inanimate things. In practice sacrifice was offered to a multitude of Gods, and Goddesses, demigods, and the semidivine creatures with whom we share our world. But as all these divinities derive from and participate in Prajapati, sacrifice assists the Gods in the destructive/creative process that binds the Universe as One. In this way sacrifice becomes an act of procreation.

In many ways we can see a parallel between the Vedic perspective and views of Western philosophy related to sacrifice in the Religio Romana. In Stoic physics, according to Diogenes Laertius (7.137), kosmos is used in three ways, the first of which is that it refers to the divine, “the peculiarly qualified individual consisting of all substance, who is indestructible and ingenerable, since He is the manufacturer of the world order, at set periods of time consuming all substance into Himself and reproducing it again from Himself.” In the same way Vedic Prajapati created the world out of Himself, consumes all back into Himself, and procreates once more in the never ending diastolic and systolic cycle of the divine that permeates the Universe. In Platonism the divine is an extension of the One. It emanates downward through different levels of being until finally, permeating all things, the divine brings cosmic order to chaotic matter. Likewise do all things return to its source, the components of matter in the body are recycled in physical universe, the soul redeemed into the World Soul of the Timaeus, the spirit, or pneuma, is carried further upward into the plethora where finally the mind, or nous, is reunited with the divine Nous. In Neoplatonism the Henadic Gods and all things emanate from the One That Is. Everything that can exist lies within “its cause, proceeds from it, and reverts upon it (Proclus Theol. Prop. 35).” These ideas from Greek and Roman philosophy are what lies behind the rational given by Sallustius for Roman sacrifices. “The happiness of every object is its own perfection, and perfection for each is communion with its own cause.”

Through sacrifice we return to the Gods the divine essence within an offering. Through our action something of our own divine being joins that of the offering on the altar, and both are met by the divine presence of a Goddess or a God who receives the offering. An accretion of divine essence, or numina, builds at a sacrifice, focused in the altar, strengthening the divine, feeding it as it were. One element of sacrifice is thus to feed the Gods or to stoke the flow of the divine as it cycles through us and all around us. Failing to act through sacrifice, we would no longer be connected with the divine in Nature and within ourselves. As Vishnu says in the Gita, the result would be disaster. “These worlds would collapse if I did not perform action; I would create disorder in society; living beings would be destroyed.” In drawing down a divine essence, as another element to our sacrifice, we are blessed ourselves since divine within us is further strengthened. And for the offering, properly released through ritual, it is blessed in that its divine essence may return in full communion with the Gods as it, too, is strengthened and recycled through the continuous flow of the divine. If there is any thought connected to Roman sacrifice that has to do with sin, it is only that ritual impurity would cut us off from sacrificial rituals, and that would thereby deprive ourselves of companionship with our ancestors and community, partnership with the Gods of Nature, and communion with the higher Gods. But then, as Varro said, “The superstitious man fears the Gods; the religious man reveres Them as he would his parents, for They are good, more apt to spare than to punish (frag. 47 Card.).”