Forgive us our sins

This petition in the Our Father comes in two halves. The first half deals with us. The second half deals with us dealing with others. Not unreasonably, I’ll dig into first half first.

We ask here “Forgive us our trespasses,” and there is language problem. Catholics use the word “trespasses,” as do many Protestant denominations. Some Protestants, largely Reformed, use “debts.” The Gospels Luke and Matthew dither between both words.

Trouble is both are legal phrases. For contemporary understanding, to my mind, they do not capture the sense of what we are asking. “Trespass” is going beyond one’s rights, like deliberately jumping a fence marking posted land and getting caught where you shouldn’t be. “Debt” doesn’t strike me as any better. It suggests something legal gone amiss.

“Sins” is the rendering in contemporary English, produced by the Consultation on English Texts, representing 22 Protestant denominations in the U.S. and Canada, plus the conferences of Catholic bishops in Canada and in the U.S.. But just because almost everyone agrees to “sins” doesn’t mean everybody actually uses it. “Trespasses” by far is favored most, except in those places where “debt” yet rules. It does get complicated.

But I like “sins.” There is no mistaking what that word means.

At its Hebrew root “sin” means “to miss the mark.” It evokes an archer aiming carefully at what should be an easy target. You take your best shot and, stupidly, somehow you missed. “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” as St. Paul has it. (Rm. 3:23)

If we were talking about bowling, missing a strike is watching your ball veer straight for the gutter. There it rumbles mocking all your careful preparation and everybody can see it. Nice, huh?

A little while before in the mass we were made to confess our sins “to God Almighty, before the whole company of heaven, and to you, my brothers and sisters.” As if we need any more gawkers, huh?

Thankfully, the language is formally ritualized. Otherwise it would be a downright red-faced embarrassment.

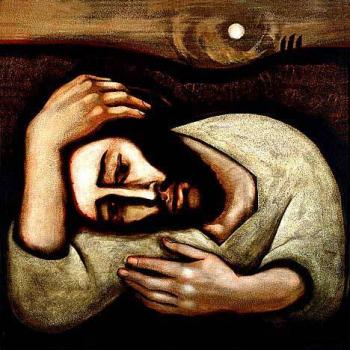

The fracture of sin is relational. Unlike the legalities of debt or trespass, sin fundamentally indicates a rupture of trust. The relationships that are most dearly betrayed are entangled and almost always they involve people we know best and should love most. A harsh word, a mistaken intent, a belittling, things do boil over. This is where sin cuts deepest: between you with God, between you with neighbor and God.

Equally and perhaps more personally devastating than any other sin, we may also talk of that betrayal of one’s self, that time when fear or shame or both drove you to abandon your own best principles.

To ask forgiveness under those conditions is to seek relief from guilt. There’s another thing. Guilt isn’t very popular. Pop therapists tell us guilt will unfavorably impact our sense of self, and we wouldn’t want that, now would we? We don’t like guilt any more than we like admitting the sin that produced it.

We could skip both, you know. People do. Since everybody knows that guilt lowers self-esteem, don’t you really need therapy more than forgiveness, therapy to overcome low self-esteem caused by guilt from sin? Detach the guilt from the act, or the act from the guilt, and you can get on with the business of living a guilt-free life. No guilt = no sin. See, all fixed.

If you are in that situation (and honest, who isn’t), denying the reality guilt due to sin, try this. Tune in any country “somebody-done-somebody-wrong” song. There you’ll find ample helpings of both for most of the year. If we had ways of turning all that anguish and angst into an energy source, we’d be done with fossil fuels by next weekend.

So sin is real, and so is guilt, but life in Christ is more than either.

There is a higher reality. The resurrection of Christ shows us a new world. We begin to look at ourselves ― our sin and our guilt ― in the light of the risen Christ.

An ancient prophetic promise stirs to life and we get a look at our new reality: “I will forgive their iniquity, and their sin I will remember no more.” (Jer. 31:34b) The Eucharistic remembrance (anamnesis) of Christ’s sacrifice for our sin becomes God’s forgetfulness (amnesia).

Christ is raised. Whatever the sin, however deep the guilt, we are embraced and from within that embrace Christ once more launches us as a New Creation. We turn once more and ever again to the life God desires for us. For a plain old fashioned word like sin, there’s nothing more refreshing than a plain old fashioned forgiveness. Repeat as necessary.

Russell E. Saltzman lives in Kansas City, Missouri. His latest book is Speaking of the Dead. http://alpb.org/books/speaking-of-the-dead/ He can be reached at [email protected] [email protected] and on Twitter @RESaltzman. https://twitter.com/RESaltzman