When you pray, say “Father.”

The Our Father is an old familiar friend to us. It may have been the first full paragraph any of us ever memorized. This usually was by mimicking the grownups, our child voices trailing a beat behind, piping up on the last syllable. But that’s how we learned it.

I also know it may well be the last full paragraph to leave our consciousness. While tending the dying as a pastor, I have seen the lips of the comatose move silent cadence as the prayer was spoken.

So this prayer is an old, old familiar friend, in good times and bad. There’s the trouble. Old reliable friends are very familiar friends; we think we already know everything there is to know. But we shall shake it up in this series and see if something new falls out.

So we stop to ask: “What are we praying for when we pray the Our Father?”

The very first thing we learn is who it is to whom we are praying. The answer is astonishing. “When you pray, say ‘Father.'” (Lk. 11:2).

Jesus encourages us to speak to the Lord Most High God of Israel as Father from the intimacy of childhood. Jesus would have said Abba in Aramaic; in Greek, the language of the New Testament, it becomes Pater, and to English, Father. The name is warm, intimate, cozy, suggesting tenderness, affection, accessibility, strength.

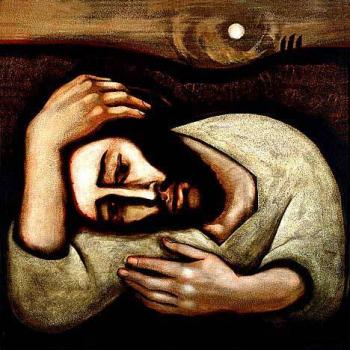

“When you pray, say Father” and then we know the Lord Most High God of Israel is our Father, with whom we may curl up in safety, whose arm is ever-ready for our strength, and chasing the monsters of life from under the bed.

As Pope Francis put it, “calling him ‘Father’ puts us in His confidence, like a child talking to his dad, knowing that he is loved and cared for by him.”

We learn next, this father’s name is a holy name. That’s troubling. “Holy” sometimes isn’t anything we really want, and we don’t like it much in anybody else either. Holy Joes never have any fun; neither do Holy Janes. Worse, “holy” can become self-righteousness, a brittle piousness, or sanctimoniousness, or moral superiority. “Holy” used this way are they of the tisk-tisk Tweet and the virtue signal on Facebook, with eyebrows hoisted looking down on the rest of us struggling with our wants and our problems and our temptations. “Holy” sometimes isn’t holiness at all.

Real holiness is intended to do something and do it perfectly. An engine finely tuned, woodwork turned to exacting specification ― these things do as they ought. They are at peak potential, exactly as intended, and with smooth, unfettered effectiveness they fulfill their purpose.

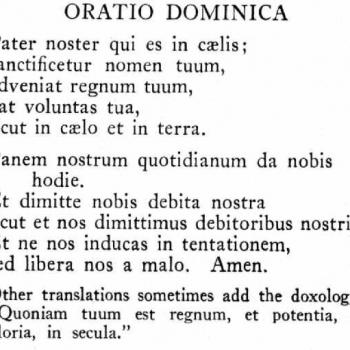

When we declare that Our Father’s name is holy, hallowed, we’re hardly telling God something he doesn’t already know. Instead, we are asking that God’s name will work among us as a holy name ought to work. The literal Greek reads “let it be-being holyized the name of you.” “Let it be always becoming holy.”

We ask for his name “holyized” among us; that it will do for us and in us what his holy name is supposed to do, that we may hear his voice in clarity and truth.

We want this hallowed name to clear away the noise and speak above clutter and debris in our lives, so that we will hear his Word when we use his name, that God’s name will do among us his hallowed purpose without hindrance, that we may know he is our Father.

God’s name, thus, is linked to God’s Word. This is important. It means that when we call God’s name, we are also asking for God’s Word.

We ask for an authentic Word in this world where we are daily assaulted by words that finally mean so little. We are asking God, by praying God’s name, for a Word, his Word, a clarion Word rising above above all the nattering clatter filling life.

What is God’s Word? God’s Word is a story. It is the story of Jesus. It is a true story.

My youngest son when little liked me to sing while driving. He’s 32 now doesn’t ask for that quite as frequently. His favorite, though, when he was 4, 5, or 6, was The Wreck of Old 97, that song about the brave engineer crossing the White Oak Mountain “doing ninety miles an hour.”

And he always asked, “Is that a true story?” Yes, as it happens. But he understood even then when he was little, a true story, it means something. It means we’ve heard something more than just a tale, more than a rumor, but something fundamental about the world, about the people in the story, and about ourselves.

We Christians assert that the truest story ever told is also the greatest story ever told. So when we pray God’s name, that’s the story we seek.

We pray, “Our Father in heaven, hallowed be thy name.” What we ask is: Father, let your name work in us as it should, as we ask it to; give us your Word, tell us a story, tell us a True story.

And the Lord Most High God of Israel scoops us up in his arms, dangles us on his lap as Father, and tells us a story that really has but one word: “Jesus.”

Russell E. Saltzman lives in Kansas City, Missouri. His latest book is Speaking of the Dead. He can be reached at [email protected], on Twitter @RESaltzman, and on Facebook as Russ Saltzman.