Yes, you read that title correctly: God is not powerful.

I don’t write such words lightly. I realize that many will not actually read beyond the title, so for those of you still with me, thank you.

Of course, some might call it semantics, or perhaps perspective. I believe our expectations of “power” differ in ways both small and great from who God actually is, how God relates to us, and how we ourselves function in this universe. By the way, this theology is framed by scripture, not the other way around.

First, consider with me the following:

- What if in the process of expecting so much of God, we ourselves do less than we can or should to prevent bad things from happening within the reach of our arms?

- What if the world we live in is more a result of humanity’s collective lack of action rather than God’s power, or lack thereof?

- And what if a better understanding of God’s relationship with us resulted in you and me seeing new opportunities for a world that is less like how many of us live, and more like what God desires for us?

More Than Words

Classical Aristotelian thought categorically dictates that a power is something that is given and received. Powers may be possessed, but do not have an intrinsic provenance.

Contrasted against power is a quality. Qualities are intrinsic, meaning they belong essentially, as in part of an identity, not a gift that has been received.

Can these definitions be applied to a scripturally informed theology? Let’s try:

God is many things, but before all else, God is love.

It isn’t good enough to just say God is “loving,” because that limits love to motives and actions. God actually is love, homoousios (ὁμοούσιος) meaning “of the same substance,” in the same way the Nicene Creed establishes Christ and the Holy Spirit as one with the Father, made of the same stuff. That “stuff” is love…it is the DNA of God.

I don’t mean to suggest that the nature of God is as simplistic as just love…but then again, perhaps it is that simple.

Everything God is—creator, savior, comforter, even holy—may be ultimately defined by love. There is no other way to reconcile God’s immanence and transcendence.

How many times have we heard about the “power” of love? Just off the top of my head, Huey Lewis and the News in Back to the Future, Celine Dion covering Jennifer Rush and Air Supply, and that Hillsong worship song, along with probably millions of other examples.

But is love really a power?

In terms of a biblical understanding, the word most used in the New Testament for power is dunamis (δύναμις), which is strongly connected to the English concept of “dynamic,” meaning to have the force, power, ability, or capacity. But most of the times the word is used in the NT, it is contextually indicated to refer to “inherent power, power residing in a thing by virtue of its nature, or which a person or thing exerts and puts forth.”

Or in other words, it is used to describe what we would more closely define as a quality. Obviously, I’m sticking to my guns here. In its New Testament usage, power is qualified as inherent or intrinsic, which if it must be qualified in those terms, is a quality—that’s the very definition of qualification.

Okay, fine, so I untied the knot: love is a quality, God is love, so God’s uncomposed uncreated nature could be better defined as a quality rather than power, ergo God isn’t powerful…

And I’m still not totally satisfied, and you shouldn’t be either.

Is Love Power?

Since 1947, The European Society of Analytic Philosophy has published a quarterly journal called “Dialectica” that regularly features academic papers about this sort of thing in a philosophical rather than theological context.

Cherry-picking issues here and there, I have discovered that there is actually a very spirited debate among philosophers whether natural properties are qualities or powers or both, and for twenty years it has been considered one of the greatest arguments in the metaphysics of properties. A couple of authors have famously characterized powers as both intrinsic and relational.

That last word, relational, of course sparks my interest, because how can something be both intrinsic and relational?

That theory is properly termed dispositional essentialism, and challenges both categoricalism (powers are powers and qualities are qualities) and dispositionalism (everything is an essential quality, and power is antiquated, inferior—an obsolete concept). Adherents to dispositional essentialism possess the nuanced view that powers and qualities are not mutually exclusive properties, that a quality can also be considered a power and vice-versa.

What is tempting about this theory when applied to theology is that love is both a quality (God is love) and a power (humanity has the power to love one another), and that it may be proven by its relationality three ways: 1) we love because God first loved us, 2) the greatest commandment of loving God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength, and in the same way loving our neighbor as ourselves, and 3) Christ’s command to love one another as God has loved us.

But okay, that really doesn’t prove anything. The relationality of love is obvious and undeniable. It still doesn’t make love a power.

There are other inane theories that attempt to postulate another alternative middle ground, the most prevalent called Quidditism. Following that view, the essence of a property such as love is constituted by its internal or self-contained nature (called quiddity) and contingencies affect how it is related. Applied theologically, it could imply that the nature of love changes somehow between God and humanity, or is conditional—which is patently false.

Love isn’t love unless it is unconditional.

So, does power even exist?

Does God Consider Himself Powerful?

Maybe this is a better question: according to scripture, does God ever actually say he has power?

The answer is a surprising no.

Jesus foretold his disciples that they will “receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on [them].” It is an odd word choice, almost as if Jesus went out of his way to connect power with the arrival of the Spirit without specifically attributing the Spirit with power.

Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase The Message actually eliminates any reference to power in that passage: “What you’ll get is the Holy Spirit. And when the Holy Spirit comes on you, you will be able to be my witnesses…”

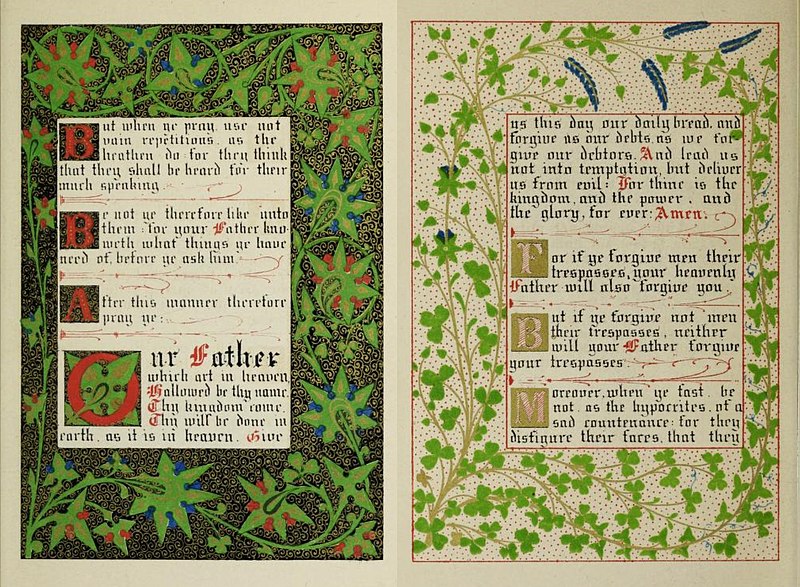

And consider the more infamous doxology to the Lord’s Prayer:

“For thine is the kingdom,

and the power,

and the glory,

for ever and ever.

Amen.”

Those words are not present in most modern translations because the earliest manuscripts do not include it at all. It is a later addition, thought to be appended in a congregational worship setting, probably an interpolation of 1 Chronicles 29:11, a prayer of David, who is not God.

So just because David said God had powers, and because worshipers added those approximate words to the end of the Lord’s Prayer four hundred years after Jesus lived, died, and was resurrected (Chrysostom was the first to refer to the presence of the doxology “in some copies”) doesn’t mean Jesus ever said any such thing.

According to the gospel of John, Jesus did speak of God’s glory, and asked for God’s glory in return; he prayed that his disciples would have the full measure of his joy within them, but he didn’t say a word about power.

In the book of Revelation, the twenty-four elders cast their crowns at the throne of God, and said he was worthy to receive power—but that is not the same thing as God himself saying that he has power.

So, the Old Testament, then. There is the Hebrew word toqeph (תֹּקֶף), meaning “power, strength, force, or energy,” and scripture does not record God using that word ever to refer to himself or his nature or his actions. It is closely related to taqeph (תָּקַף) which is a verb rather than a noun, and means “to prevail over, overpower.” Not once does scripture state God ever used such a word to refer to or describe any of his actions.

If God never called himself powerful or said he had power in any way, why should we?

Let’s Try This Again

Earlier, I asked a question I didn’t answer: is love really a power? Then I compounded it when I was describing dispositional essentialism and wrote that humanity has the power to love one another.

So, again, perhaps God isn’t powerful, but God is undeniably love. And the same love that God embodies has been given to us in a reckless sacrificial act. If one ascribes to traditional categorical philosophical analysis, then love is both the essential quality/identity of God and a power to us.

This is more than just semantics: This is about who God is, and who we are.

Then I saw before me the solution, simple but profound, and grasped the laces I had unknotted and tied them in a bow:

“Dear friends, let us love one another, for love comes from God. Everyone who loves has been born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love. This is how God showed his love among us: He sent his one and only Son into the world that we might live through him. This is love: not that we loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sins. Dear friends, since God so loved us, we also ought to love one another. No one has ever seen God; but if we love one another, God lives in us and his love is made complete in us. This is how we know that we live in him and he in us: He has given us of his Spirit. And we have seen and testify that the Father has sent his Son to be the Savior of the world. If anyone acknowledges that Jesus is the Son of God, God lives in them and they in God. And so we know and rely on the love God has for us. God is love. Whoever lives in love lives in God, and God in them. This is how love is made complete among us so that we will have confidence on the day of judgment: In this world we are like Jesus.” (1 John 4:7-17 NIV)

Love is not transformed between God and humanity—rather it transforms us…so that in this world, we are like Jesus.

That we may love others as we have been loved.

We are born human, original sin as our essential quality, opposed to God who is in nature the pure essential quality of love. When we experience the love of Christ, God’s love is made complete in us, we are transformed into a new creation, born again in love, the incarnation of Christ within us as simple as our heart becoming his Bethlehem.

When we are transformed by God’s love and in turn love others, is this love a power or a quality?

To those we love, they are experiencing a power—something that is relational. We experience the power of holy love as Christ’s disciples in the presence of the Holy Spirit, bearing witness of this fact.

Maybe it can be said that God isn’t powerful…but by doing so, it must be added that when God’s love is completed in us, there is nothing more powerful than loving others.