Many people, especially Christians, consider God strictly in terms of power. This is a mistake.

Not that God isn’t powerful (a topic I explored last year while reviewing one of the most insightful books I have ever read). But when we choose to approach our relationship with God primarily in terms of power and abilities, it can lead us to distort our understanding of who God is.

I mean, how good is your relationship with someone you don’t really understand?

For example, on a human level, I spend a considerable amount of time writing. Some could fairly call this activity a profession, however by no means does writing define my relationships with my family, or my roles as a spouse, father, or friend.

We are more than just the things we do, and so is God. Thankfully, God’s divine nature isn’t an unknowable mystery, but is revealed relationally and may be characterized scripturally by the term holy.

But for most people, holiness is a term that is vague and doesn’t mean much of anything.

This is true both inside and outside the church. I have many friends (even pastors and other church leaders) who have an extremely limited understanding of holiness and are actually suspicious of its role in ministry.

This is a problem I even wrote about several years ago. Then and now, the concept of holiness is far removed from its actual application in ministry.

But on the other hand, because holiness remains such an elusive mystery for so many, its intentional removal from strategic disciplemaking has resulted in confusion, bias, and outright exploitation by legalists and others within the church who seek to promote political social agendas.

Old Testament Considerations

The concept of holiness in the Old Testament is deeply rooted in the Israelites’ historical experiences and their covenant relationship with God.

One of the central events shaping this relationship is the Exodus from Egypt. When Moses led the Israelites out of slavery, their deliverance was understood as more than an isolated acts, but expressions of God’s faithfulness. God was committed to them not just because they were the descendants of Abraham but because of who God is—one who fulfills promises.

The giving of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai further expands Old Testament notions of holiness. In this pivotal moment, God established a covenant with the Israelites by providing a framework for them to live in a manner that reflects their mutual relationship. Rather than a moral code, the commandments were a promise of responsiveness between humanity and God—that God’s holiness would be manifested in every facet of existence, including worship, ethics, respect for living creatures, and the importance of maintaining healthy interpersonal relationships.

More precisely, Old Testament scripture also supports the idea that holiness includes consecration for divine purposes—a definition that extends to encompass objects, actions, motives, individuals, and even God. In Hebrew, the word qadash (קָדַשׁ) is a verb commonly translated to fit that specific scriptural interpretation. This presentation extends beyond mere moral conduct to encompass various dimensions of existence.

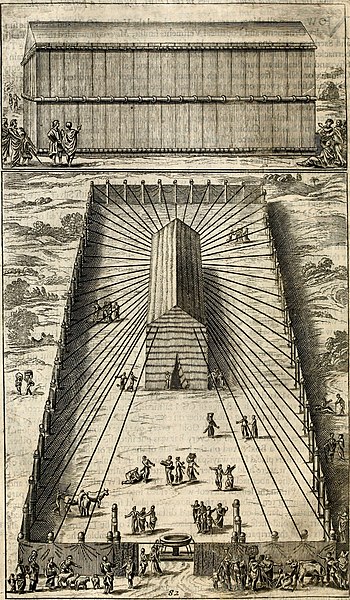

For example, the Ark of the Covenant, the tabernacle, and various utensils used in worship were sanctified to serve specific purposes. These consecrated objects were treated with reverence and represented the holiness of God’s presence among the people.

Additionally, rituals, sacrifices, and ceremonies prescribed in Old Testament law were not merely religious customs but acts of worship that distinguished the Israelites as holy people. Individuals were set apart to serve specific roles, such as prophets, priests, and kings. The consecration of these individuals involved not only external rituals but a commitment to live in relationship and accountability to God.

Even beyond outward actions, the consecration definition of holiness extends to human and divine motives. God is intrinsically holy, and this holiness was the standard for the Israelites to emulate in their personal and communal lives.

A heart that is holy is dedicated to God and filled with genuine love, devotion, and faithfulness.

All of these examples present anything that is holy as purposed to directly respond to God’s love in a way that is loving. If every motive God has is loving, then individuals who choose to respond in a way that serves God’s love become holy themselves.

This predicated relationship is otherwise served by the concept of prevenient grace, because it establishes that God’s divine holy love precedes or “goes before” human inclinations to love.

In other words, we are holy because God is holy, and we love because God first loved us.

New Testament Considerations

Mother Teresa once wrote, “Love is a fruit in season at all times and within the reach of every hand. Anyone may gather it and no limit is set.”

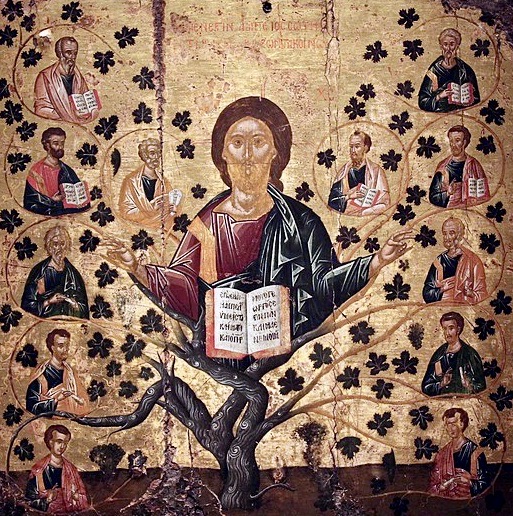

The gospel of John depicts Jesus presenting the same concept to his disciples on the night he was betrayed:

“I am the vine; you are the branches. Those who abide in me and I in them bear much fruit, because apart from me you can do nothing… My Father is glorified by this, that you bear much fruit and become my disciples. As the Father has loved me, so I have loved you; abide in my love. If you keep my commandments, you will abide in my love, just as I have kept my Father’s commandments and abide in his love. I have said these things to you so that my joy may be in you and that your joy may be complete. This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you.” (John 15:5, 8-12, NRSVue)

The analogy of the vine and the branches representing the holy relationship between Jesus and his disciples is not only apt, it applies to anyone who abides in Christlike love with Jesus.

There is a structure to this, as illustrated by the vine, branches, and fruit. This relational aspect of holy love is theologically founded by the incarnation itself: Jesus is the Word made flesh, and he exemplifies God’s holiness expressed immanently with humanity by love. Although the branch withers and dies if cut away from the vine, it grows and flourishes when its connection is healthy, and produces fruit in season.

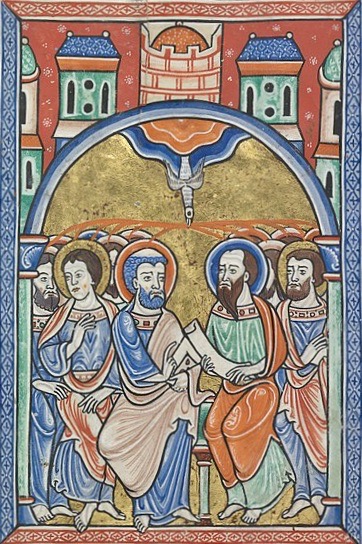

And as the vine and the branches and the fruit are all nourished by a common source, so our loving connection to others and to Christ is fueled by the Holy Spirit. Certainly, Jesus promised that we would remain connected to him and one another forever by the Spirit, telling his disciples, “You know him because he abides with you, and he will be in you” (John 14:17b, NRSVue).

The same real relationship Jesus had with God, their holy connection of love, is manifested by the presence of the Holy Spirit. Jesus prayed to the Father that the Holy Spirit would unite his disciples together with them: “The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me” (John 12:22-23, NRSVue).

The Spirit not only gives us the same righteous DNA of love as Jesus and the Father, this relational connection of the Spirit transforms us because holy, spirit-filled love does not function the same as worldly, non-loving relationships: “When he comes, he will prove the world wrong about sin and righteousness and judgment” (John 16:8, NRSVue).

Both Sides Now

So, love is the core of holiness.

But not just any derivative definition of love—a love that is reckless and sacrificial, that overcomes anything and forgives everything but never condemns. It’s the kind of love that would lead a father to sacrifice his only son for sinners, the sort of love that connects us to one another and the divine, that transforms us to accept others in love.

Holiness is a love that sets us apart from the rest of the world because it comes without any conditions. Nothing is held back—everyone is worthy of all the love we have to give.

Christ’s theology of holiness, along with Old Testament precepts rooted in the unique relationship between the Israelites and God, emphasizing consecration for divine purposes, finds further reinforcement in Paul’s perspective expressed by his letter to the Romans. Paul believed that holiness leads us not only to acceptance of others, but of ourselves, and ultimately worship:

“Family, considering the boundless mercies of God, I implore you to dedicate your bodies as a living sacrifice—a holy offering that God finds pleasing. This is your authentic and meaningful act of worship. Don’t let the world shape you into its mold. Instead, let your mind be renewed, bringing about a transformation that helps you recognize God’s perfect will—what is good, pleasing, and truly perfect.” (Romans 12:1-2, author’s translation)

Holiness is a transformative journey to Christlikeness, empowering and equipping us for service in God’s kingdom.

As disciples of Jesus, we are invited to “let your mind be renewed, bringing about a transformation that helps you recognize God’s perfect will—what is good, pleasing, and truly perfect” (Romans 12:2). More than just a mandate to evolve our understanding and acceptance of others, this spiritual transformation is nothing less than an alignment with God’s will, gifting us with the empathy, compassion, and inclusivity of our Savior and King.

Holiness calls us to stand against the judgment and stigma created by hatred, bigotry, and prejudice in our violent world. Rather than legalistic moral purity, accusations, threats, trials, dismissals, or shunning in any form, holiness seeks to love others, responding to their needs without control or coercion. If we allow the enemy to dictate fear and condemnation into our relationships, then we are not the church, and our actions and attitudes are anything but holy.

Legalists wrongly believe holiness is dependent upon some complicated definition or formula of what they think God finds holy, but this is scripturally myopic. God desires us when we offer our imperfect, flawed selves wholly and completely. We don’t have to be straight, male, white, or use binary pronouns to be acceptable to God. The Holy Spirit is who makes us holy—not any ritual, practice, deed, or lack thereof.

Any other “holiness” theology is legalistic idolatry, and no more holy than a golden calf molded from the jewlery of superstitious slaves.

“…You Just Have to Listen.”

My wife and I were watching TV the other day, and it occurred to me that holiness is hearing the voices of those who are unable to speak, giving love a voice that the rest of the world would not hear or listen to.

We were streaming the Netflix miniseries All the Light We Cannot See, based on the superb 2014 Pulitzer-Prize winning novel of the same name. In the story, the protagonist’s father tells her repeatedly, “Everything has a voice: you just have to listen.”

A couple of decades ago in my own neck of the theological woods, the small corner of Wesleyan thought that has historically been called the “Holiness Movement” was filled with whispers and clucking tongues when a respected church leader presented a paper that opined, “The Holiness Movement Is Dead.” The general idea was that churches stopped doing things the way they were done about a hundred years ago, and so the Holy Spirit somehow “stopped moving” among believers.

Of course, this is puerile and ridiculous, not unlike specious arguments such as “The Church is in Exile” that made the rounds in Christian universities and seminaries about 25 years ago, or the ridiculous fear-mongering “Make the Church Holy Again” ravings of some who claim “The glory of God has departed,” as if the Holy Spirit left the church in a snit without even announcing “Elvis has left the building.”

All of these ideas suffer the same poverty of insight that offers some magical formula the church must gulp down to revive itself, as if the church actually belongs to us to begin with, or that we must behave a certain way to enjoy the good graces of God.

To borrow a phrase from a writer of fiction, people who hold such ideas have quite literally given up good and evil for behaviorism. Instead of hearing the voice of our neighbors and loving them as we love God and ourselves, so many are inventing behaviors and practices intended to seduce a God who already loves us.

Holiness is loving those God loves, which is everybody without exception. It’s listening to voices that others don’t want to hear, even in the church. And it’s living God’s love through relationships that transform our world one life at a time.

Everyone is worthy of all the love we have to give. It’s time people who call themselves holy listen to the voices of even the least of these.