This is post number two in a series I’m working on about why we tend to blame victims in our society. My church has been covering this topic in it’s latest sermon series (which you can listen to online). Also, I’ve been taking a seminary class on the Psalms and Wisdom Literature, which contain some interesting, and often contradictory messages about victim blaming.

In my first post in this series, I discussed one possible reason for why we blame victims: We are afraid of a world outside of our control. Today, I’m going to discuss another possibility.

2. We Don’t Want to Face Our Responsibility and Privilege

This point is related to the first point, but I think expands on it a bit. I think we often blame victims either out of guilt, or out of fear of (or just unwillingness to) facing up to our own roles and responsibilities in a situation.

When I talk about facing up to our responsibility, I’m not just talking about perpetrators who blame their victims in order to escape punishment. Obviously, those people will not want to own up to their responsibilities. But when we think about how our society oppresses some people, while privileging others, things get more complicated.

For instance, why might a middle class person–who knows that just one lay-off, one trip to the hospital, one natural disaster could easily knock them out of the middle class–insist that they earned what they have, and that poor people just need to stop being so lazy?

Of course, part of this relates to the first reason–we are afraid of a world outside of our control that makes us vulnerable to victimization.

That world outside of our control is scary, though, not just because it means bad things could happen to us. It is also scary because a world outside of our control means that, when we are successful, we cannot always take full credit. We usually have to recognize the privileges that helped us get to where we are, and we have to recognize that we are not inherently better than those who do not share those privileges.

I think there is also guilt there, and maybe a feeling of helplessness. Those of us who have nice things, while others barely have enough to survive, usually know deep down that this isn’t right. We feel guilty or helpless. Often this guilt is counterproductive leading us to denial and victim blaming.

We don’t know how to change the world, so we squash those bad feelings by telling ourselves, “I earned this. Those people could have this too, if they’d just _____.”

For things to change, we must face those “bad feelings,” and move beyond guilt and beyond denial, and toward solidarity. There are ways to do this, and we should start practicing those ways.

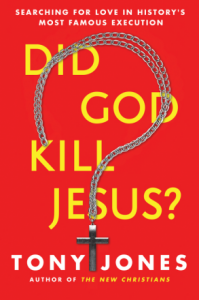

[Image is a James Baldwin quote reading: “I’m not interested in anybody’s guilt. Guilt is a luxury that we can no longer afford. I know you didn’t do it, and I didn’t do it either, but I am responsible for it because I am a man and a citizen of this country and you are responsible for it, too, for the very same reason”]

White people–who have a much easier time getting into college, or getting a job, then a person of color–might accuse a black person who can’t find a job of not trying hard enough in school.

Privileged men–who have been taught their whole lives that they are entitled to women’s bodies–might be unwilling to give up that sense of entitlement. They may even tell a rape victim that she was “asking for it,” rather than admit that they have treated women as objects in the past, contributing to a culture that convinces some men that they have a right to rape, and that they can get away with rape.

The world can be chaotic sometimes. It’s certainly not always just, and that can be scary. But sometimes there is order to the world, and sometimes that order is deliberately unjust–benefitting some at the expense of others. Sometimes we victim blame, because we do not want to own up to the ways in which we benefit from, and contribute to this unjust world.

Other times, we victim blame because, in order to hold up an unjust order, we need to control people. This will be the topic of my next post.

Until next time, what privileges do you have that others do not? How can you turn feelings of guilt into action (rather than victim blaming), and into solidarity with those who do not share your privilege? Are there any privileged mindsets that you need to let go of, and challenge others about?