Review of Wrath of the Titans, Directed by Jonathan Liebesman

By ALEXIS NEAL

Demigod Perseus wants nothing more than to raise his young son in the idyllic quiet of his simple fishing village–just as he promised his late wife Io. An unexpected visit from his father Zeus reveals that the increased lack of belief among mortals has severely weakened the gods, and that the Titan Kronos (father of the gods) is on the verge of breaking out of Tartarus, the prison of the underworld where he’s been trapped since before the dawn of mankind. Perseus is at first reluctant to get involved, but when his village is attacked by a chimera, he decides to help Zeus restrain Kronos. In the meantime, however, Zeus himself has been captured by his brother Hades (who seeks revenge for being exiled to the underworld) and his son Ares (who resents Zeus for his preferential treatment of Perseus); they plan to hand Zeus over to Kronos so that Kronos can use what remains of Zeus’ power to fuel his escape (in return for which assistance, Hades and Ares hope to be granted continued immortality when Kronos takes over). Perseus—with an assist from former god (and divine weapon-smith) Hephaestus, fellow demi-god and mischief maker Agenor (son of Poseidon), and Andromeda, queen of Greece—must now journey to the underworld to save Zeus before Kronos drains Zeus of the last of his power, breaks free, and destroys all of humankind. Mythological shenanigans ensue.

Demigod Perseus wants nothing more than to raise his young son in the idyllic quiet of his simple fishing village–just as he promised his late wife Io. An unexpected visit from his father Zeus reveals that the increased lack of belief among mortals has severely weakened the gods, and that the Titan Kronos (father of the gods) is on the verge of breaking out of Tartarus, the prison of the underworld where he’s been trapped since before the dawn of mankind. Perseus is at first reluctant to get involved, but when his village is attacked by a chimera, he decides to help Zeus restrain Kronos. In the meantime, however, Zeus himself has been captured by his brother Hades (who seeks revenge for being exiled to the underworld) and his son Ares (who resents Zeus for his preferential treatment of Perseus); they plan to hand Zeus over to Kronos so that Kronos can use what remains of Zeus’ power to fuel his escape (in return for which assistance, Hades and Ares hope to be granted continued immortality when Kronos takes over). Perseus—with an assist from former god (and divine weapon-smith) Hephaestus, fellow demi-god and mischief maker Agenor (son of Poseidon), and Andromeda, queen of Greece—must now journey to the underworld to save Zeus before Kronos drains Zeus of the last of his power, breaks free, and destroys all of humankind. Mythological shenanigans ensue.

As you can see, there’s kind of a lot going on here. It’s a very busy film. And, I confess, it may have seemed more than usually busy to me on account of I watched it in IMAX 3-D, sitting in the front row. I freely admit that my viewing situation may have affected my ability to follow the plot, and may have made things seem more chaotic than they would otherwise be if viewed in a less overwhelming format.

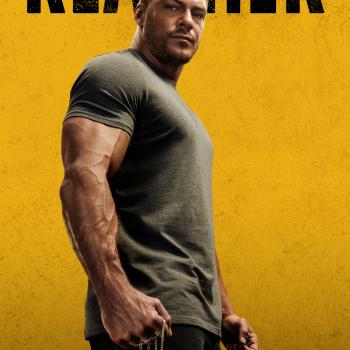

The acting here is merely middling, for the most part. Sam Worthington does what Sam Worthington does best: look earnest and serious while beating down the opposition (and taking several beatings himself). Rosamund Pike is lovely enough while still exuding the strength we expect from an ancient queen. Tony Kebbel, as Agenor, provides what limited comic relief is to be found in such a ‘serious’ action film, and he does it well (though Bill Nighy, as the slightly loony ex-god Hephaestus, has a few shining moments of his own). The real acting heavyweights here are, of course, Ralph Fiennes (as Hades) and Liam Neeson (as Zeus) who, when decked out in beards, robes, and long hair, look eerily alike. They are the real source of pathos in the film, though Perseus’ son Heleus does what he can to make us care about him. I found myself oddly invested in this divine family drama, as Zeus seeks reconciliation with his estranged brother, and Hades finds himself face to face with a costly opportunity for redemption. Ares, on the other hand, who was constantly on the verge of a temper tantrum, was not nearly as compelling.

The effects were fairly well done, as well they should be, since they were, for the most part, the real stars of the show. Kronos–essentially a cross between a Balrog on steroids and the Chernabog from the “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence in Fantasia–is quite overwhelming; it is clear that the odds are not in humanity’s favor, no matter how many troops they marshal or how many aging gods are on their side. Other classic mythological beasts–Pegasus, the chimera, the Minotaur, etc.–are creatively and effectively handled. The action sequences are sometimes confusing and difficult to follow (though see above re: my particular viewing experience)–then again, they moved so quickly that there wasn’t much gore on screen, and what little there was passed by too quickly to really be absorbed. ‘Action violence’ at its finest. (Hence the PG-13 rating.)

The script is rather lackluster, to be sure, but no one goes to a movie like this for the witty dialogue. This is not “John McClane v. Kronos”–Perseus is far too serious to exchange quips with his opponents, and Kronos himself never really utters any intelligible sounds beyond the occasional angry roar of ‘Zeuuuuuus!” Still, for all its unimpressive writing, the movie itself was fairly enjoyable.

I was particularly struck by the underlying religious themes of the film–to the extent that such a movie can be said to have themes. The ‘theology’ of long-abandoned ancient gods is always fascinating–there is a sort of necessary past-ness to telling the tales of ancient gods; they are ‘dead’, and that reality must be dealt with (though of course, as man-made creations, they were just as dead even at the height of their popularity (Isaiah 44:9-20; Jeremiah 16:20; Habakkuk 2:18-19)). These gods are inevitably presented as relying upon the worship of mankind as the source of their power. (See also Neil Gaiman’s American Gods). They need worship in order to exist, in order to rule. Because no one worships them now, they no longer exist. As religious fervor declines, their powers wane–like Tinkerbell, they feed on the faith of men.

Of course, even at the zenith of their power, these gods are far from sovereign, and by the time this narrative takes place, prayer is seen as a joke. The gods are fighting for their very lives–how can they possibly help mankind in its fight against real problems? The conclusion of the film portrays a world post-deity, where men are the arbiters of their own destinies and no longer seek assistance from the gods. This does not appear to be seen as a bad thing, at least as far as Perseus and the others are concerned. And given the capricious cruelty and immorality of the Olympians, perhaps they are right. Humanity is better off without such gods. It is less clear whether the filmmakers wished to extend this cynicism to other religions–whether they feel all gods are similarly dependent on (or created by) mankind, and that mankind has moved past the need for God.

I must admit this moment of ‘freedom’–no more gods to victimize them or save them–rang hollow to me, even ominous. Though the Olympians are nothing like the God of the Bible, the thematic parallels were obvious. To me, the idea of living in a post-God universe (were such a thing even possible) is not liberating–it is chilling. I found myself thankful for the existence of an eternal, sovereign God whose power does not depend on my belief, who is never surprised, whose plans are never upset, and who intervenes on behalf of His people in response to prayer.

There are other, more positive religious themes here as well–selfish ‘love’ is contrasted with loyalty and self-sacrifice, and forgiveness plays a pivotal role in the fate of mankind. Grace begets grace, in a surprising (and likely unintended) reflection of the gospel.

But let’s be honest. This is not a message movie. Sure, on one level, every movie has a message—the very word ‘media’ implies content. But a theme perceived is not necessarily a theme intended, and as Christian viewers, we modify our judgments accordingly. In this case, to the extent any underlying ‘message’ was intended, I suspect it was more along the lines of ‘Oppose tyranny’ or ‘Neutrality is unsustainable in the face of true evil’ or something equally unobjectionable.

And anyway, at the end of the day, you don’t go see a movie like this because of the Important Life Lessons it imparts. I know I sure didn’t. You go see it because you want to see Perseus beat the living tar out of the mythological beasts of ancient Greece, while Liam Neeson and Ralph Fiennes lurk in the background wearing beards and robes. In that sense, the movie is a complete success. It delivers enough action and adventure (and effects) to choke Cerberus. If that’s your cup of tea, then drink up, because there’s plenty to be had.