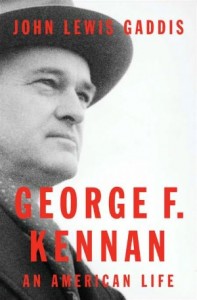

Review of George F. Kennan: An American Life, by John Lewis Gaddis

Magisterial, thousand-page, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographies are usually reserved for presidents, emperors, generals, and saints. With John Lewis Gaddis’ definitive George F. Kennan: An American Life, the epic treatment is given to a 20th Century American bureaucrat. Who was George Kennan, and why does he deserve an exhaustive work by a renowned historian?

Kennan was the intellectual father of “containment,” the strategy of applying “counterforce” to the Soviet Union’s attempts to expand its influence. Containment was a smashing success; indeed, it was instrumental not just in helping the United States win the Cold War, but in keeping it cold, not hot. That makes Kennan one of the few genuine grand strategists in American history and (almost) justifies the attention given him despite his relatively humble job titles.

George F. Kennan: A Life is a perfect match between subject and author. John Lewis Gaddis established himself as our foremost historian of the Cold War with books including The United States and the Origins of the Cold War (1972), Strategies of Containment (1982; revised 2005), and The Cold War: A New History (2006). Gaddis made plain his admiration for Kennan in his earlier work, yet showed an uncanny ability to place him in context and see at least some of his weaknesses.

Kennan selected Gaddis as his authorized biographer in the early 1980s. Their agreement was all an historian could ask for: Kennan gave Gaddis full and complete access to all his papers, including his personal diaries and correspondence, and asked almost nothing in return. Kennan did not review the book or exercise any control over its contents. The only condition was that Gaddis publish the biography after Kennan died, which Kennan, then nearing 80 years old, expected to be soon. He would live another twenty years. The book opens with Gaddis recounting some painfully funny portions of Kennan’s diary: Kennan burdened with guilt for having lived so long, lamenting that his long life was hampering Gaddis’ career. That was Kennan.

Kennan, a Foreign Service Officer in the United States Department of State for 27 years, became influential within the American government for writing the famous “long telegram” from his post in Moscow in 1946, and followed it up with the even more famous “X” article in Foreign Affairs in 1947. The two writings offered a penetrating analysis of the Soviet Union and a sharp set of recommendation for how the United States should respond. They were foundational documents for U.S. Cold War strategy. Foreign Service Officers and Ambassadors to this day aspire to write the next “long telegram” and win instant clout throughout the government, but they typically forget that Kennan was in his early 40s when he wrote his dispatch and had spent two decades in relative obscurity, laboring in humble jobs and accumulating hard-earned expertise on his chosen subject. He lived for nearly 17 years in eastern Europe and Russia, far longer than most diplomats and career Foreign Service Officers today, and spoke fluent German and Russian. Kennan was a specialist with deep subject-matter expertise long before he earned a seat at the table of grand strategy. He was also a vivid, strong writer.

The seat his fame earned him was as the first Director of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, from 1947 to 1949, a job created by the new Secretary of State, George C. Marshall. Even in this post, Kennan was just an upper-level bureaucrat, but his influence far exceeded his job title and became an ideal towards which all bureaucrats (fruitlessly) aspire. His first planning paper at the State Department became the template for the Marshall Plan. He almost single-handedly formulated U.S. policy towards Yugoslavia (when Tito dared show independence from Moscow) and China during the waning years of that country’s civil war. Many of his papers were approved with little to no revision as official statements of U.S. policy under the Truman administration.

Gaddis makes this seem to be a natural result of Kennan’s brilliance, but he leaves out an important part of the story. Kennan was able to exercise such influence partly because the United States’ foreign policy apparatus was in a state of flux and hadn’t yet taken on the complex and highly-institutionalized form it would later assume. The National Security Council had just been created in 1947 and was not yet in full operation. The NSC Planning Board of the Eisenhower years was still several years in the future. Kennan had the good fortune to be assigned a planning role several years before similar jobs were created elsewhere in the government. Kennan’s influence naturally grew to fill the void. As a result, he was functionally acting as Truman’s National Security Advisor before that job was created. Kennan played the hand he was dealt with savvy, but it was apparent early on that the State Department was not the right place for such a job.

Why wasn’t Kennan ever tapped for high positions in the American government? He had the sort of career trajectory that should have culminated with his nomination as Secretary of State. Part of the answer is bad timing: Eisenhower was elected in 1952 and Kennan had become too affiliated with the Truman administration. By the time Kennedy was elected a new generation of Democratic foreign policy professionals was ready to take the lead. But part of it was that Kennan wasn’t a very good diplomat. He was ejected from the Soviet Union for tactlessly (though accurately) comparing the Soviets to the Nazis, and he was equally inept at smoothing relations among his colleagues within the State Department. Bureaucrats with reputations for thin skin and a tendency to rock the boat don’t get picked for high office.

Kennan was the voice of realism within the American government, and he continues to be the patron saint of skeptical realists today. He saw earlier than anyone the Soviet Union’s cynical opportunism and untrustworthiness and formulated the idea of containment as a response. But the same realism led him to push for a recognition of the limits of the United States’ own capabilities. As the Cold War developed, he came to oppose most of what “containment” came to stand for. He constantly worried about overstretch and warned against undertaking idealistic initiatives abroad. He opposed the Truman Doctrine–that the United States will aid any democracy under threat of external attack or internal subversion–because of its idealistic, global, even utopian overtones.

Realism is in vogue amongst war-weary Americans hungover from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya and fixated on fiscal overstretch. Indeed, Kennan’s realism has much to commend it. First is Kennan’s own track record. He accurately saw, earlier than anyone else, the Soviet Union’s basic character as a totalitarian, untrustworthy regime. He formulated a coherent response to it, and he more or less accurately predicted the USSR’s internal collapse from its own weaknesses and contradictions (although it took longer than Kennas thought). Kennan was a prime mover in the initiation and design of the Marshall Plan, especially the condition that the Europeans cooperate to design their own recovery rather than having American bureaucrats dictate terms from Washington– a feature imitated far too rarely in later reconstruction and stabilization efforts. Kennan was also far readier than most to understand that communism was not a monolith, and that the United States could afford to approach different communist regimes differently–an insight more often overlooked than heeded. Later he came to oppose the Vietnam War and the nuclear arms race and he took up the standard of environmentalism. Kennan’s pragmatism, self-doubt, and caution would be useful appendages to the contemporary foreign policy establishment.

But other features of Kennan’s career should serve as a caution against the short-sightedness, cynicism, and amorality inherent in realism. Kennan was instrumental in cutting off aid to the Chinese nationalists because he thought they were a lost cause on whom the United States should waste no more money–but failed to see that by abdicating any role in China, the United States became a de facto abettor of the totalitarian Chinese communists’ seizure of power. Kennan opposed the diplomatic recognition of Israel for fear of offending the Arab states and thought the democratization of Japan was a waste of time, both excellent examples of how realist calculations based solely on the short-term national interest sometimes result in utterly stupid conclusions. He thought the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 a meaningless gesture, but later historians have argued that its articulation of human rights became a powerful tool for Soviet and Eastern European dissidents in the 1980s. Kennan was hesitant about the formation of NATO in 1949 and opposed its expansion in the 1990s, fearing that it might overstretch American capabilities, a rare instance in which Kennan’s foresight was wrong. Kennan was also a prime example of east-coast, academic snobbery: he loved Kennedy but despised Reagan less because of their foreign policies and more because the former was a cultured Bostonian who courted Kennan while the latter was a California simpleton who ignored him.

Gaddis, a realist himself, tends to highlight the best of Kennan’s judgment and often stays silent about the drawbacks of realism. That is a forgivable weakness: scholars spend decades studying subjects they admire, less often ones they think foolish. Gaddis’ biography is a rewarding work, especially for Cold War history buffs and students of American foreign policy process. It is also a model for how to write an authorized biography. Kennan’s humility and transparency in allowing such a biography are exemplary. Kennan’s quirks and sins are very much on display. He despised American culture, grew to know the world outside America’s borders better than that inside, had streaks of elitism and racism, and admitted (with not much repentance) to infidelity and a wandering eye. Gaddis, who spent hours and hours interviewing his subject, admits that Kennan could be “a little weird.”

It is proverbial that secular historians routinely ignore their subjects’ religious lives. We get almost nothing about Kennan’s beliefs except a perfunctory mention of a Presbyterian background, a Calvinist sense of pessimism, Kennan’s belief in the importance of religion for inculcating morality, and a confession of syncretic, heterodox faith late in life. There is nothing to suggest Kennan had anything more than the American establishment’s belief in civic religion, but Gaddis doesn’t explore the question deeply. We get surprisingly little detail on Kennan’s relationship with his children. And the biography drags a bit in its latter portions: Kennan lived so long that he actually spent a majority of his working life as a scholar and successful historian (he won two Pulitzer Prizes) after he left the foreign service–but a narrative of Kennan writing and expressing opinions on current events over which he had little influence becomes a little repetitive.

In addition to his Pulitzers, Kennan won the Albert Einstein Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and dozens of other awards and honorary degrees. After he testified to Congress about the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the Congressmen gave him a standing ovation (this is out of character for Congress). For a bureaucrat, he became remarkably well-known, influential, and honored–partly because he was always something more than just a bureaucrat. Kennan had the mind of a philosopher and the pen of a poet, but chose, out of a sense of duty, to apply both to the problem of America’s role in the world. Few bureaucrats can claim as much, and few countries can ask for much more.