By Christian Hamaker

Joaquin Phoenix is no stranger to mainstream audiences. The actor made a name for himself in M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs and Ridley Scott’s Gladiator, and was later nominated for the Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of Johnny Cash in Walk the Line (a role for which he won a Golden Globe). He further honed his skills by working on smaller films from auteurs such as James Gray (The Yards, Two Lovers, The Immigrant), Paul Thomas Anderson (Inherent Vice) and Spike Jonze (Her). Next up, as anyone with an internet connection surely knows by now, is his portrayal of the grimly humorous Batman villain in The Joker, directed by Todd Phillips (The Hangover).

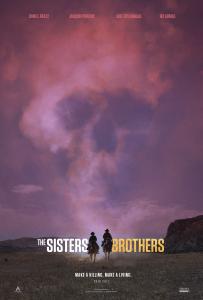

Those who can’t see Phoenix pulling off the mordant humor of the Joker are advised to see him in The Sisters Brothers, an oddball Western about siblings (the other is played by John C. Reilly) who in the 1850s make a living as hired killers. There’s Eli (O’Reilly), who’s looking forward to doing something else with his life besides murdering people, and Charlie (Phoenix), whose drinking and volatile temperament make him well suited to his chosen vocation.

Their boss, the Commodore (Rutger Hauer), has sent them to find John Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal, with one of his unidentifiable accents), who will lead the brothers to their target, Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Ahmed). For what reason the brothers aren’t sure, but it’s not their job to ask questions. They just carry out their assignments.

Traveling through Oregon and down to California, the brothers quarrel with each other and experience setbacks such as spider bites inside the mouth (a scene that made the preview audience gasp and moan), a horse with a badly infected eye and even—brace yourself—amputation of a human limb. And yet the script, skillfully adapted by director Jacque Audiard (Rust and Bone) and Thomas Bidegain from Patrick DeWitt’s book of the same name, puts across the novel’s humor often enough to keep the film—and viewers—from sinking into despair or wanting to walk out of the theater in disgust.

While Phoenix’s Charlie can be chillingly single-minded in carrying out the brothers’ assignments, O’Reilly’s Eli gives the movie whatever tenderness its story allows—whether through his quest for female companionship or his tenderness toward his wounded horse.

The story’s shifting perspective—from the Sisters brothers to Morris and Warm—help keep The Sisters Brothers moving when the film’s pace threatens to become too stately, as does the occasional gunfight. Lensed by Benoit Debie (Spring Breakers), the vistas are striking as the seasons change and the brothers continue their murderous mission, but the film’s most memorable visual moment may not be a scene of natural beauty but a more magical, almost mystical moment: When Warm, a chemist who promises his unique solvent can, when added to water, help make gold visible in a riverbed, finally puts his solution to the test in front of the brothers and Morris.

The Sisters Brothers doesn’t have profound lessons, but it does show the consequences of greed and the corrosive effects on the conscience that results from pursuit of a dark calling on behalf of merciless men. Set to an offbeat, unexpectedly percussive soundtrack from Alexandre Desplat, The Sisters Brothers isn’t life-changing, but it’s a strong platform for its two lead actors and a reminder that the ugliness of life, even among killers in the 1800s, can be touched by moments of transcendence, mercy and brotherly love.