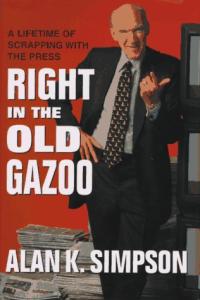

Every couple of years when teaching a class on Congress, I have to read a number of biographies about and books by US Senators. Sometimes this is tedious or infuriating (as when I’ve got to slog through Bernie‘s or Ted‘s tripe), and sometimes it’s delightful (Teddy Roosevelt wrote a biography of Thomas Hart Benton!). And sometimes it’s just melancholy, as with Al Simpson’s book about wrestling with the media as a politician, Right in the Old Gazoo: What I learned in a lifetime of scrapping with the Press. And in case you’re wondering what a “gazoo” is, it’s a horse’s rear. Which tells you something about what he thinks about the press–though Simpson isn’t big on politicians either:

“Know the difference between a horse race and a political race? In a horse race, the entire horse runs!” (230)”

This isn’t exactly a memoir, though there is plenty of personal narrative and reflection in it. Instead, Right in the Old Gazoo is exactly what the subtitle promises: a set of reflections on Simpson’s battles with the press and his attempts to get them to live up to their own (mostly unknown) code of ethics. Simpson is clear that he is not guiltless in these fights, and that at time his temper or his sense of humor or his occasionally abrasive personality got the best of him and he said or did things he shouldn’t have. But he is also clear that the press has become more concerned with getting big headlines than with reporting the truth, and that it is utterly unwilling to admit fault or submit itself to scrutiny.

Again, that’s not to say that politicians are innocent here:

“First, reporters and politicians must lower the volume on our rhetoric….As for politicians, we must stop engaging in raw partisanship solely for its own sake. These days any senator who reaches out to the other side is too often instantly labeled disloyal, untrustworthy, a patsy, a wimp, and a traitor. Those who can actually do good work on both sides of the aisle can often lead a harrowing existence in the Congress.” (256)

What makes this such a “melancholy” book is that it was written in 1997. Simpson was making these arguments twenty-five years ago–and the situation hasn’t improved. Consider what Simpson had to say about how Supreme Court confirmation hearings were affected by the Bork hearings:

“There was a time in American when a president could nominate someone for such an office with the expectation that the Senate would conduct a fair, reasonable discussion of the person’s qualifications, and then hold a fair, sensible vote for or against confirmation. This assumption usually held true even when a president chose someone whose political leanings were different from those in the majority party of the Senate. I had always respected that tradition. In my view, the president had a right to appoint to the Supreme Court any justice he wanted, so long as they were qualified to do the work. I vote that way. The tradition I speak of was extinguished with the sabotaging of Robert Bork. Thereafter, the confirmation process became a stage for petty partisan bickering. After Bork came Senator John Tower, Zoe E. Baird, Lani Guinier, and on and on. What a sad thing for our country.” (202)

There’s really nothing revolutionary here—this has been a common complaint about the Senate for years (to say nothing about the House!). But I think it’s worth reflecting at least for a moment about how we Evangelicals engaged this problem Specifically, we have done little to deescalate political rhetoric, to reach out and work with opponents on issues we can agree on, or make good-faith offers to compromise not our principles, but on practical policy. This is not to our credit. We are at a rough moment in our history, and polarization is a large part of that. And while it is not our job as Christians to fix the problems of the world (it’s our job to witness to the Gospel of Jesus Christ), we can at least strive not to make existing problems worse. If that means we scale back extreme rhetoric, try our best to speak the truth (and expect our public figures to do the same–regardless of their political party), and work with those with whom we politically disagree, then we should do so. This twenty-five year old book is a good model of someone who–no Evangelical himself–made political career of doing those things, and doing them well.

It’s also a heck of a lot of fun, so there’s that too : )

Dr. Coyle Neal is co-host of the City of Man Podcast an Amazon Associate (which is linked in this blog), and an Associate Professor of Political Science at Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, MO