Review of The Mummy, Directed by Karl Freund

By ALEXIS NEAL

You really should know better than to read aloud anything you find in an ancient tomb in Cairo.

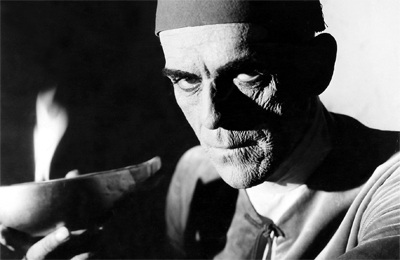

But when the long-lost Scroll of Thoth is discovered, a certain archaeologist’s assistant decides to do just that: read it aloud—and in the presence of the mummified remains of the priest Imhotep, no less. It is hardly surprising, then, when the archaeologist returns to find that his assistant, clearly already deeply stupid, is now completely mad with terror, while the surprisingly mobile Imhotep is nowhere to be found.

Ten years after Imhotep lumbered off into the night, the archaeologist’s son Frank is following in his father’s footsteps. One day, a rather imposing Egyptian by the name of Ardeth Bey conveniently turns up to direct him to the tomb of Princess Ankh-es-en-amon, who just so happened to have been Imhotep’s lover all those many, many years ago. It is the find of a lifetime, and the archaeological team is thrilled. But Ardeth Bey is an odd duck, to say the least, and he seems fixated on Frank’s main squeeze Helen Grosvenor, who is herself of (partial) Egyptian descent. Helen seems more and more distant with each passing day, and a rash of mysterious deaths point to a force more powerful than mere man. Just who is Ardeth Bey, and will Frank be able to save Helen from his nefarious plan?

If you enjoy classic cinema or are at all interested in the historical roots of the modern day monster-craze, I commend The Mummy (1932) to you as a must-see film. Boris Karloff, known to many in my generation solely for his voiceover work in How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1966), proves that he is more than just a scary face and creepy voice—he can really act. There is a pathos to his portrayal of Imhotep/Ardeth Bey—a deep exhaustion and pain that makes him almost sympathetic, even as he’s using his undead mojo to kill anyone who would keep him from his lady love. The makeup and effects here are impressive as well, particularly for such an early film. Freund makes good use of the power of suggestion, exciting the imaginations of his audience to do the work for him—The Mummy remains genuinely creepy more than 80 years after its original release. In this case, less really is more.

The narrative here, like that of many monster stories, is at its heart a romantic one: Once upon a time, Priest Imhotep loved Princess Ankh-es-en-amon. When death separated them, Imhotep was so desperate to be with her again that he acted in deliberate rebellion against the gods he previously served by stealing the Scroll of Thoth in order to bring Ankh-es-en-amon back to life so they could be together. He chose human love over faith.

Imhotep was caught in the act and, as punishment for his transgression, he was buried alive in complete mummy regalia. Now, having been accidentally resurrected by the nitwitted archaeologist’s assistant, Imhotep picks up where he left off, searching for his long lost love, whose soul apparently resides in her modern day ancestor, the young Helen Grosvenor. Along the way, Imhotep is perfectly willing to kill anyone who gets in his way. His ‘love’ for Ankh-es-en-amon results in disrespect—and violence—toward others.

Then, it turns out that the final step in his long-planned reunion with Ankh-es-en-amon is Helen’s death—only by killing the body where the soul of Ankh-es-en-amon dwells can she be freed to be with Imhotep forever. This plan doesn’t seem to go over too well with Helen (or, it is implied, Ankh-es-en-amon), but that doesn’t stop Imhotep. What she wants doesn’t matter. His ‘love’ for Ankh-es-en-amon overrides all other considerations. He ‘loves’ her so much that he is willing to kill her—against her will—to be with her.

We tend to think of ‘love’ as a good thing, a wonderful thing. Love is a many-splendored thing; love lifts us up where we belong; all you need is love. We read romance novels, watch romantic comedies (or dramas, if crying’s more your thing), and dream of our own grand romance. Heck, the bible extols the merits of love (I Corinthians 13)—how could it be anything other than good?

There are [] occasions on which a mother’s love for her children or a man’s love for his country have to be suppressed or they will lead to unfairness toward other people’s children or countries. (23-24)

Yet we see time and again that ‘love’—or something we call ‘love’, perhaps erroneously—can have catastrophic consequences. C.S. Lewis alludes to this reality in his masterful work Mere Christianity:

People do awful things in the name of love. Seemingly ‘loving’ parents raise spoiled children (or controlling parents become so determined to protect their children that they deprive them of valuable life experience). Stalkers insist that it is ‘love’ that drives them to monitor their beloved’s every move. Abuse is perpetrated (and endured) in the name of love. And in The Mummy, ‘love’ results in dishonoring God (well, his god, anyway, but we do the same thing), disrespecting others, and ultimately, despising the object of affection.

Why is this? What has gone wrong?

According to Scripture, the reason is simple: Love for our neighbor is not the end-all be-all of life. We were designed first and foremost to love God. (Exodus 20:2-3; Matthew 22:37-39)

If we get this wrong—if we love a person more than we love God—then our love is corrupted and twisted into something far from lovely. In fact, C.S. Lewis would argue that it is not really love at all:

You cannot love a fellow creature fully till you love God. […] There is but one good; that is God. Everything else is good when it looks to Him and bad when it turns from Him. (The Great Divorce 100, 106)

This corrupted—and incomplete—‘love’ controls us to the point where we, like Imhotep, are willing to throw over the God we claim to serve, willing to disobey Him whenever His commands interfere with our pursuit of our earthly love. We hate and despise and even attack those who would stand in our way. And ultimately, our ‘love’ can lead us to hurt the very person we claim to love most of all.

If we elevate our love for another person over all other considerations, destruction awaits.

However, when we love God first, our love for others remains pure. (Matthew 6:33) It is better and stronger than it ever could ever be on its own. (I John 4:21) He is the one who loved us first, sending His son to die in our place while we were yet sinners. (Romans 5:8) That love—the same love that enables us to love Him in return (albeit poorly)—enables us to love others made in His image. (I John 4:9-11)

When we remember our great sin against God, freely forgiven in Christ, we are able to forgive others. When we genuinely believe that our treasure is in heaven and our loving Father will care for our needs, we can give generously. When we are secure in the knowledge that God loved us enough to die for us, we are free to love even when those we love don’t love us back. We have an advocate who intercedes for us in heaven, so we intercede for others. We have been blessed, so we welcome the opportunity to bless others. We serve and sacrifice for others joyfully because of Christ’s sacrifice on our behalf.

We love because He first loved us. (I John 4:19)

_______________________________________________________________

Alexis Neal is an attorney in the Washington, D.C., area. She regularly reviews young adult literature at www.childrensbooksandreviews.com and everything else at quantum-meruit.blogspot.com.