At the very beginning of the Christian church, before it was ever called “Christian” or often called “church,” it was a large group of new believers in Jesus gathered in Jerusalem, figuring things out as they went along. They were learning how to be disciples of a Lord who, having ascended into heaven, could no longer be literally followed from place to dusty place. Jesus’ original disciples from the Galilee ministry were now the official apostles of the dangerous Jerusalem work. Having followed well, they could now lead. And the Holy Spirit was Lord and giver of life, moving through their preaching and testimony with effective power.

When they needed help with the administration of the community of believers, they commissioned deacons: “men of good repute, full of the Spirit and wisdom” (Acts 6:3). One of those deacons, the most outstanding one described in the book of Acts, was Stephen. No empty vessel, this Stephen: Luke tells us that he was also “full of faith and the Holy Spirit” (6:5) and “full of grace and power” (6:8). He did great wonders among the people and had a persuasive testimony.

We don’t have to guess what his sermons were like, because we have one of them in full: Acts chapter seven reports his final sermon, a great jeremiad that ranges across the whole field of God’s history with his people. Stephen had been hauled in on trumped-up charges of blaspheming the temple, and he apparently decided to give the people what they wanted: His speech climaxed in an assertion of the ineffectiveness of sacrifices and the fatuity of thinking of the temple as a place where God could be confined.

Duly provoked, the mob encircled him: “when they heard these things they were enraged, and they ground their teeth at him” (8:55). It is at this moment that Stephen had a vision unlike any other New Testament vision short of John’s Apocalypse. The narrator gives us precious little description and no details, but he reports what Stephen saw, and what he said:

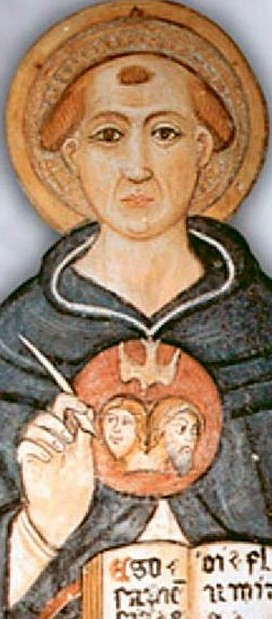

But he, full of the Holy Spirit, gazed into heaven and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God. And he said, “Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God.”

What did Stephen see? At this last moment of his life, he was given a clear sight of ultimate spiritual truth: Jesus Christ, recognizably himself and fully human, exalted to the position of power and glory at the side of God. What all believers know to be true, Stephen saw to be true.

As his sermon makes evident, Stephen knew the Scriptures well, and what he saw was a visual confirmation of several crucial prophecies from the Old Testament. Chief among these was Daniel 7, in which the prophet saw “one like the son of man” who came before the fiery throne of “the Ancient of Days” in heaven, and was given “dominion, and glory, and a kingdom.” The other great prophecy that Stephen saw fulfilled in this vision was the oracle of Psalm 110: “The LORD says to my Lord, ‘Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies your footstool.” When Stephen looked into the opened heaven and laid eyes on Jesus Christ beside the glory of God, he must have recognized that these (and many other) words had been fulfilled, and known that he was looking on the ultimate reality behind all the oracles. “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit,” he cried as they stoned him.

Every believer needs to be fully persuaded that Jesus Christ is at the right hand of the Father. Not many of us should expect to be given the kind of immediate spiritual vision that the first martyr saw in his moment of death. In the absence of such a vision, how can we know this stupendous thing to be true?

The main answer is that we can believe it on the authority of God’s promise. But the New Testament holds out something rather more than just the sterile affirmation that “God promised x, so x must be true.” Consider the book of Hebrews, and the way it parallels Stephen’s encounter.

Hebrews seems to be a kind of sermon based on Psalm 110, returning again and again to the imagery of that key passage, “the LORD says to my Lord, ‘Sit at my right hand'” (1:3, 1:13, 8:1, 10:12-13, 12:2). Hebrews also makes use of other images from Psalm 110, notably the oracle, “You are a priest forever, according to the order of Melchizedek.” And it quotes this Psalm, as it quotes so much of the Old Testament, in a unique way. The way Hebrews quotes the words of Scripture, it leads us into the experience of hearing God himself as the speaker of these words.

The opening sentence sets us up: “God…has spoken…to us.” Even as it grounds the claims of the Old Testament to be the oracles of God (“to the fathers through the prophets”), Hebrews asserts that God has spoken now, in these days, in Christ. It calls on us to pay attention to what is said, and cautions: “Today if you hear his voice, do not harden your hearts.” All these explicit markers of oral speech and cues for auditory attention are in place. And all along the way, Hebrews is doing something sneaky with its scripture citations. It is training us, verse by verse, to hear God speak.

Take, for example, the first major argument of the book: that the Son is superior to angels. If we imagine the author of Hebrews as a kind of attorney, he does not so much marshal a case for the Son’s superiority as he simply calls his first witness to the stand and then steps aside. The first witness, in this case, is God. Hebrews establishes the superiority of the Son by showing what kind of things God says to the Son, and contrasting that with the kind of things God says to angels. To the Son he says, appropriately, “you are my Son.” And about him he says things like “I will be to him a father… let all God’s angels worship him… your throne is forever and ever,” and “you laid the foundation of the earth in the beginning.” But about angels he says things like, “he makes his angels winds, and his ministers a flame of fire.”

For anyone with a high christology, it’s easy enough to prove the Son’s superiority over angels. Hebrews goes out of its way to make this its first major argument because it wants an excuse to get us listening to the words of the Old Testament as the words of God. Once we’re tuned in to that voice that sounds anew from the ancient oracles, we never stop hearing it. To read Hebrews in this spirit is to hear God speak, testify, promise, and take an oath, telling the Son “sit at my right hand… you are a priest forever.” We hear, in these words from God’s own mouth, what Stephen saw.

As the message continues, we also hear in Hebrews the voice of the Son himself, speaking from his place at the right hand of glory. He says to the Father, “I will tell of your name to my brothers,” “I have come to do your will… as it is written of me in the scroll of the book,” and he says to us, “I will put my trust in him.” And almost at the end of the book, he promises “I will never leave you nor forsake you,” so we can confidently reply, “the Lord is my helper, I will not fear.”

Stephen’s speech in Acts 7 is in many other ways a great introduction to some of the key themes of Hebrews. We were told in Acts 6:7 that “many priests believed” the gospel, and Stephen was preaching powerfully in that context, perhaps to that kind of audience. Faced with the real threat of persecution, he spoke boldly and fixed his eyes on Jesus, the author and finisher of his salvation. Some scholars have argued that Luke may in fact be the author of the letter to the Hebrews, partly on the basis of shared vocabulary but partly on the basis of similarities like this: the faithfulness of God, the obsolescence of the temple, the superiority of Christ, and the vision of Jesus exalted to the right hand of God. It’s an interesting hypothesis about this anonymous sermon-turned-letter.

But the crucial thing is the exaltation of the Son, Jesus, to the right hand of God. Stephen saw it. Most of us will not, no matter how earnest, or curious, or in danger we may be. But if we hear Hebrews rightly, we can all hear the same thing Stephen saw.