The church of St. Servatius in Siegburg, Germany has a treasure room full of medieval art and relics. Among the artifacts is a portable altar crafted around the year 1160 by the workshop of Eilbertus of Cologne.

Eilbertus was a master craftsman of Romanesque metalwork and enamel decoration, a sturdy artistic medium which withstands the centuries with minimal fading or decay. The colors remain brilliant after nearly a millennium. But Eilbertus was also a skillful iconographer, whose fluency with the symbolism of Christian art equipped him to construct dense and elaborate visual arguments.

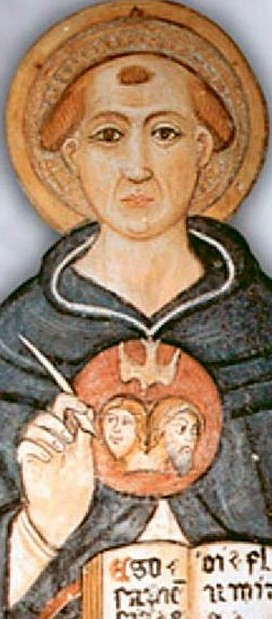

Consider the top of the altar-box (click through for a larger display of the image):

Ranged in bands along the top and bottom of it are the twelve apostles of the Lord, labeled “apostoli domini.” Running down the right border are three ways of depicting Christ’s victory over death: at the bottom is the post-resurrection appearance to Mary Magdalene in the garden, at the center is the empty tomb (“sepulchru domini”) with sleeping soldiers and the three women seeking the Lord among the dead where he is not to be found, and at the top is the ascension, “ascensio Christi.”

The event of the resurrection itself is not directly portrayed, of course, but Eilbertus juxtaposes three images of the resurrection’s consequences: the presence of the Lord to his people, the absence of the Lord from the tomb, and the ascension of the Lord by which he is now both present to us (spiritually) and absent from us (bodily) until his return.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, three pictures placed together in significant visual proximity are not increased simply by addition of ideas, but rather by a remarkable multiplication of meaning.

But it is the left border that showcases Eilbertus as the iconographic and doctrinal master that he is. In the middle is the crucifixion of Jesus, where the Son of God is flanked by his mother Mary and John the evangelist, as well as by the moon weeping and the sun hiding his face. At the foot of the cross, from the feet of the savior runs the blood of the crucified, and as it runs down the hill of the skull, it crosses a rectilinear panel border in which is inscribed “passio Christi,” the passion of Christ.

The blood runs out of its own frame and into an adjoining visual space, a space in which Adam (clearly labeled “Adam,” which is Latin for… Adam) is rising from a sepulcher. Adam’s arms are outstretched in a gesture of reception, but they also set up a powerful visual echo of the outstretched arms of Jesus. Adam’s tomb and its lid are arranged perpendicular to each other, so that Adam’s body is framed by an understated cruciform shape of the same blue and green colored rectangles as Christ’s.

Eilbertus is making another visual argument here: Where the two crosses cross, salvation takes place. Because the second Adam bends his head and looks down from his death, the first Adam raises his head and looks up from his. Eilbertus is offering an invitation here: above are the everlasting arms, outstretched but unbent, as linear and straight as panel borders or the beams of the cross, while below the salvation is received with appropriate passivity into the bent arms of the father of the race of humanity. Redemption is accomplished and applied, and at long last an answer is given to God’s first interrogative: “Adam, where are you?”

But even this is not the peak or extent of Eilbertus’ iconographic teaching. For that master stroke we have to look not below the cross but above it. In another pictorial space, framed by both a square and a circle, is God the Father flanked by angels. It doesn’t look much like God the Father. It looks instead exactly like Jesus, right down to the cross inscribed in the halo. Pity the iconographer who has to represent the first person of the Trinity visually.

As a general rule, the Father should not be portrayed: even in the churches that use icons in worship, stand-alone images of the Father are marginal, aberrant, non-canonical. Do you portray him as an elderly man with a flowing white beard, as if he were modeled on Moses or even perhaps Zeus? Eilbertus has taken the imperfect but safe route, and depicted the Father christomorphically: Since Christ told his disciples “If you have seen me, you have seen the Father,” it stands to reason that if an artist decides to show the Father he should show him looking like what we have seen in the face of Jesus. Well, this is a problem not even Eilbertus can solve, and even though other options might be worse, this christomorphic Father is nevertheless a rather regrettable solution.

But if you avert your eyes from that difficult figure, you will notice the dove of the Holy Spirit ascending from Christ on the cross. The dove imagery is of course not found at the end of the gospels ascending from Golgotha, but rather at the beginning of the gospels, descending at the Jordan, onto the scene of the baptism of Christ. Eilbertus has moved the symbol here to provide a visual cue for something like Hebrews 9:14, where we are told that “Christ through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God.” Just as the blood broke the bottom border, the dove breaks this upper border, crossing over from the Son to the Father. The dove also breaks the crucial word, the label that makes sense of it all: trinitas, Trinity.

It’s a little word, but it changes everything. Simply by juxtaposing the death of Christ with a visual evocation of God in heaven, Eilbertus indicates that what happened once upon a time in Jerusalem, a thousand years before Romanesque enamels and two thousand years before the internet, is not simply an occurrence in world history but an event that breaks in from above, or behind, or beyond it, an event in which God has made himself known and taken decisive divine action. But by adding the word Trinity, the artist has turned scribe, and has proclaimed that what we see at the cross is in some manner a revelation of who God is. Here God did not just cause salvation from afar, but caused himself to be known as the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. And here we cannot press Eilbertus any further, because the diction of enamel and the grammar of metalwork are not precise enough to say what we must go on to say. Eilbertus has reminded us of the essential movement that we must make, has set us on the path that faith seeking understanding must follow: from the history of salvation to the eternal life and unchanging character of God.

Trinitarian theology is all about coming to terms with the precise meaning of that movement, and for that task we need not images depicting the truth, but words: the form of sound doctrine given in the teaching of the apostles, the interpretive assistance of classical doctrines, and the conceptual redescription that characterizes constructive systematic theology in the present tense. The craft and wisdom of Eilbertus frame the discussion, but we need to have the discussion.

(This is part of the opening of the paper I gave at Southern Seminary’s Theology Conference on the Trinity, September 2013. The prezi from the talk, which allowed me to rove around the image a bit with the audience, is here.)