Do you know the work of Alan Moore? If you’re a Pagan or an occultist, you should.

Moore doesn’t think of himself as a Pagan per se, but he’s a product of the same cultural and spiritual currents that have produced contemporary Paganism. A self-declared magician and worshipper of the “sock-puppet” snake god Glycon, Moore is deeply informed by the Western occult tradition. In particular, his graphic novel series Promethea (1999-2005) is written as a primer on the classical elements, the Tarot, the kabbalistic Tree of Life, and more—all explored within the structure of a Wonder Woman-inspired superhero narrative. With a loose group of colleagues who call themselves “The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theater of Marvels,” Moore has also recorded several CDs of ritual theater, some of which have been illustrated as graphic novels.

Lest this introduction make Moore sound like a writer who writes for a niche of a niche—comics fans deeply interested in the occult—I should also say that his mainstream appeal is well-established. Best known for Watchmen (1986), a grim and satirical take on the superhero genre, Moore has profoundly influenced the direction of mainstream comics while also working to advance comics as a literary and artistic form. Several of his graphic novels have also been made into big-budget Hollywood films. These have increased Moore’s fame even as he has distanced himself from the films, which he has come to view as crassly commercial. At Moore’s demand, the film version of Watchmen (2009) does not bear his name; Moore turned over his share of the profits to Watchmen’s original artist, Dave Gibbons.

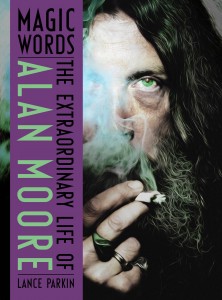

Although Moore has been frequently interviewed over the course of his career, he has been relatively circumspect about his personal life. I turned to Lance Parkin’s Magic Words: The Extraordinary Life of Alan Moore (2013) hoping for deeper glimpses of the man behind the work. In this I was somewhat disappointed, perhaps because, as Parkin portrays him, Moore’s work has largely been his life.

Although Moore has been frequently interviewed over the course of his career, he has been relatively circumspect about his personal life. I turned to Lance Parkin’s Magic Words: The Extraordinary Life of Alan Moore (2013) hoping for deeper glimpses of the man behind the work. In this I was somewhat disappointed, perhaps because, as Parkin portrays him, Moore’s work has largely been his life.

The book does spend time on Moore’s childhood and psychedelic adolescence in a working-class neighborhood of Northampton, a chapter I read with interest. In many places, however, the chapter becomes simply a history of Northampton rather than a history of Moore specifically—and this may be in keeping with Moore’s impression of himself. Moore is a lifelong resident of Northampton; his novel The Voice of the Fire is set entirely on the land on which Northampton is built, though its story begins in the Neolithic. Moore is profoundly interested in what Pagans might call “the spirituality of place,” as well as in psychogeography, a playful approach to urban geography that emphasizes the shifting relationships between people and environment. For the most part, however, Parkin covers Moore’s personal life in a handful of sentences scattered throughout the book, and usually only when it directly relates to his writing. For example, The Mirror of Love (2004), Moore’s poetic celebration of same-sex love, was originally written while Moore was part of a polyamorous marriage; he and his partners published the poem in 1988 as part of a protest against Britain’s anti-LGBT Section 28. About Moore’s daughters, the book says almost nothing except to note that Leah Moore is now a comics writer herself. Moore’s current marriage to Melinda Gebbie is mostly discussed in the context of their long-term artistic collaboration, most notably on the erotic trilogy Lost Girls (2006).

Magic Words is rich in detail, however, when it comes to Moore’s often troubled professional relationships. This level of detail may prove a barrier to the more casual reader; since I am not well-versed in the British comics industry of the late 1970s, I found my eyes glazing over a bit during the chapters that cover this phase of Moore’s career. I am much more familiar with the American comics industry, however, and I found myself engrossed in Parkin’s analysis of Moore’s loss of trust in and ultimate falling-out with his original American publisher, DC Comics.

Parkin also spends quite a bit of space on literary and cultural analysis. One chapter is dedicated entirely to Watchmen, which Parkin contextualizes within Moore’s earlier humorous and satirical work. Parkin’s argument is that critics have taken Watchmen far too seriously, producing readings that miss its irony and humor. Parkin also considers the adaptation of Moore’s novels into films, which he portrays as unsuccessful artistically, but nevertheless functioning to draw attention to the graphic novels on which they are based. Some, like the V for Vendetta film (2005), have had enduring cultural impact; Moore reported pleasure at hearing that the activist group Anonymous had adopted the Guy Fawkes masks used in the book and movie.

Parkin devotes a chapter to Moore’s magical philosophy and practice. Moore sees magic as a type of language, the proper use of which gives one access to the nature of reality. The book’s treatment of Moore as a magician is a good summary of the many interviews Moore has given on the subject, and it retains Moore’s playfulness and self-deprecating humor. Parkin is a little reductionistic, however; he sees Moore’s magical practice primarily as Moore’s way of describing and codifying his creative process, not as a potentially freestanding system of spiritual exploration and development. Readers who are primarily looking for insight into Moore’s occult work will probably be better served by reading Moore’s many interviews or by watching the documentary The Mindscape of Alan Moore (2003).

Overall, I was most impressed by the way Parkin ultimately used his detailed accounts of Moore’s professional relationships to allow the reader to evaluate industry perceptions of the writer. In the last chapter of the book, Parkin presents two competing perceptions of Moore: that his stubborn nature and blind adherence to points of principle have cut him off from the rest of the industry, leading him to create work that is increasingly inaccessible; or that Moore has distanced himself from an overcommercialized and failing comics industry, which has allowed him to concentrate on experimental multimedia work while continuing to garner critical acclaim and financial success. Parkin’s meticulous history of Moore’s working life provides the context needed to potentially make a case for either side (although it is probably obvious on which one this reviewer comes down!).

Perhaps my only real quibble with the book is that it does not fully convey Moore’s warmth, which is frequently mentioned by interviewers, and which I experienced myself in Moore’s response to a fan letter I wrote to him in my early twenties. (After sending the letter, I was floored to receive a reply package containing a kind and funny note from Moore, as well as a book, an article, and CDs relating to his occult interests!) To balance that lack, I’d like to close by relating Moore’s thoughtful advice to new magicians, which was given in 2012 as part of a group videochat to raise money for a Harvey Pekar memorial.

Well, I would say, be careful, and try to remember to keep the four basic magickal weapons–and the properties that they symbolize, more importantly–with you at all times. What you need to do is work upon your discriminating intellect, and your compassion, and your basic drive–your will, if you like–and your material circumstances, and to realize that you need to have all of these things under control if you’re going to be a successful human being or a magician, because basically a magician is just a human being writ large. […] Above all, you need compassion, because even if you’ve got the other three and everything is succeeding perfectly, if you don’t have compassion, you’ll end up as a monster. If you’ve got those four basic things, then I would simply advise you to, yes, be careful, treat all this with respect, because it’s all real, at least inside your head, and that’s the only place it needs to be real. Then, progress adventurously. Don’t be afraid to think new or unorthodox things. Try to make sure that whatever magickal insights you’re receiving are applicable to ordinary, everyday life. If they are simply describing conditions in some imaginary universe that only exists to you, they’re probably not of a great deal of use. If they’re telling you things that you can actually use in your everyday interactions with other people, that you can actually use in your own creative life, then they’re probably useful and genuine. Good luck with it, good luck with it!

[If you’d like to hear the entire group chat, there’s an .avi version with a fair bit of garbling and several cut-outs here; or, leave me a comment with some contact info and I can provide a nice .mp3 of the audio only.]

For those with a general interest in religion and comics, I’d also like to note the recent publication of American Comics, Literary Theory, and Religion: The Superhero Afterlife by my friend and colleague A. David Lewis. The book deals with portrayals of the afterlife in superhero comics–which often contrast with the afterlives of traditional Western monotheisms–as well as the evolving models of the human self that these portrayals reflect. I was involved in the editing process of the book, and I can attest that it is smart, accessible, and compelling. Plus, there’s a whole chapter on Promethea! Check it out via a university library, interlibrary loan, or Amazon.

For those with a general interest in religion and comics, I’d also like to note the recent publication of American Comics, Literary Theory, and Religion: The Superhero Afterlife by my friend and colleague A. David Lewis. The book deals with portrayals of the afterlife in superhero comics–which often contrast with the afterlives of traditional Western monotheisms–as well as the evolving models of the human self that these portrayals reflect. I was involved in the editing process of the book, and I can attest that it is smart, accessible, and compelling. Plus, there’s a whole chapter on Promethea! Check it out via a university library, interlibrary loan, or Amazon.