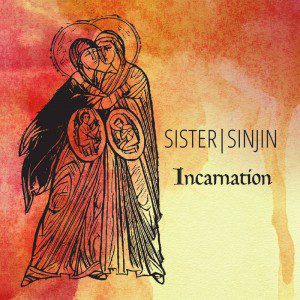

I’ve been listening to Sister Sinjin’s new album, Incarnation, as a daily Advent prayer, and I was so inspired by their dark-folk-Medieval vibe that I wrote this essay last week about women and suffering and art and faith instead of the album review that I’d set out to write.

I’ve been listening to Sister Sinjin’s new album, Incarnation, as a daily Advent prayer, and I was so inspired by their dark-folk-Medieval vibe that I wrote this essay last week about women and suffering and art and faith instead of the album review that I’d set out to write.

Sister Sinjin is Elise Erikson Barrett (vocals, keys), Elizabeth Duffy (vocals, cello, banjo, guitar), and Kaitlyn Ferry (vocals, violin, mandolin, keys). They’re three mothers who connected through various church events in their home state of Indiana, which makes them sound utterly conventional and yes, they’d agree, probably boring and maybe even irritating. “We don’t want to talk about how we’re moms in our minivans,” they told me in our interview. And yet we talked about it anyway, because they’re not ashamed of their motherhood or their Christianity or their minivans, but they know, as artists and Christians, the tendency of those in our milieu to dismiss and ignore or to rush to sanctify all that is mundane about motherhood and womanhood.

I assure you. None of this happens in these songs about what it means to be a woman, to have faith, to suffer and to create–to birth things that are sometimes lovely and sometimes broken. To wait on God so long you wonder if he’s forgotten you.

When I listen to these songs, I hear the percolating and redirected eros, the longing, suffering, loss, and pain that travels with any woman on her daily rounds. I once told an editor, after turning in an essay about cleaning out my refrigerator (no kidding), that I didn’t want to write about my stultifying domestic life ever again; I wanted to write an epic, a Greek tragedy. He told me I had an epic tragedy in my fridge. And he was right. There is everything mundane about a woman’s life. There is nothing mundane about a woman’s life.

Sister Sinjin was born when, after meeting both Duffy and Ferry, Barrett, who has two solo albums and a memoir under her belt, says she “just wanted to see what would happen musically if we all got in the same room. I thought, this could be amazing, or it could be awful. We’ll call it performance art—we’ll ask what will it look like if we just try to get together, three-year-olds and all, and do something raw and real and call the result Incarnation.”

Here are some highlights from my interview with Sister Sinjin.

Sick Pilgrim: The album is called Incarnation, but the album art is an image not of the Annunciation—the moment Mary learns that Christ will take on flesh in her womb—but of the Visitation—when teenaged Mary, already pregnant with Jesus, goes to see her much older cousin, Elizabeth, who is well pregnant with St. John the Baptist. Tell me about why this image was fitting for your project of three women artists coming together to create.

Sister Sinjin: The name is a reference to St. John the Baptist [Sinjin is an old British pronunciation of the name St. John, as fans of Jane Eyre will remember]. The three of us were looking at the ways that John the Baptist, as a prophet, was witness to the coming of Christ. His first prophecy was this leaping in his mother’s womb when Mary approached bearing Jesus. That leaping is what makes his mother, Elizabeth, recognize Mary as holy vessel. But St. John was also dependent on these two women coming together in order to recognize and declare the presence of Christ. So we were interested in how God works through women, specifically, to bring about his coming, but also in the broader discussion of how we all have the opportunity to be bearers of God’s life into the world. For us, it was by coming together as women and mothers to make music.

We wondered, too, why did Mary go to Elizabeth? Maybe it wasn’t only to serve her, maybe it was to be in the company of another woman who was experiencing the same crisis. That crisis of creation.

But Sinjin is also a reference to St. John of the Cross and his Dark Night of the Soul. Each of us had some kind of a devastating experience that broke us and then opened us, enabled us to know ourselves in ways we couldn’t have if it hadn’t happened. The stereotype is that women are emotional, even hysterical. The truth is we are trained to fear our emotions, to smash them, to suffocate them. But we all found that when we experienced devastation and heartbreak, those emotions broke open and cleared a space to love God more faithfully.

We were also inspired by the friendship between St. Theresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross. They experienced levitational ecstasy together. He burned all her letters because he was worried he was becoming too attached. They encountered God in their friendship, and it bore much fruit for the church, but at what personal cost? In these songs we wonder about costly obedience, and the fruits of honoring covenants. And also how covenant and obedience protect the creative process. If you can channel your desires, maybe they can be the seeds of creativity. Eros, a longing for consummation, is what drives the artist to create.

SP: So as Sister Sinjin, you explore all these roles: vessel, prophet, lover, mother, friend—trading roles back and forth or even playing them all at once.

SS: Yes, but maybe we identify most with St. Elizabeth at this time in our lives—or maybe it’s just that more of us have the chance to be Elizabeth than Mary or St. John. But we can all hope to model Elizabeth, coming to fruition, even later in life, and recognizing God in the presence of others.

SP: How has collaboration made creative work more enjoyable or exciting?

We hadn’t collaborated with other women before. Often we’ve found it to be, or feared it would be, a negative experience, because you sometimes have to work through a natural inclination to compete or compare. That hasn’t happened in Sister Sinjin. Instead there’s been more encouragement of one other to create. Each of us wants to push the others’ talents forward. When we came together the ground felt fertile and timely and like there was fruit just waiting there to be cultivated and harvested. When we think about solo work we don’t currently have that same sense of fecundity.

But we’ve always needed female community—our culture limits that. It certainly doesn’t happen naturally in family units or neighborhoods. Especially when you have young children, you can find yourself desperately lonely and longing for fellow travelers. We found that when our babies were young we were just in survival mode. That was a different kind of need for companionship—you just want someone in the trenches with you. There wasn’t much energy for anything else. Now that we’re in a different season with older kids, there’s energy that can be spared for a different kind of creation–not just creating human life and sustaining it.

As for collaborative work, there’s just a different kind of freedom when you don’t have sole responsibility—whether as a parent or a pastor or as a solo artist. There’s a freedom to working on the periphery, and to having the humility and space to recognize what God is doing in others, and how the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It was refreshing to have this kind of fruitful relationship with women.

SP: I think one of the most haunting tracks on the album is the last track, “Magnificat.” The refrain, which I’ve heard endlessly as a Catholic woman: “God who is mighty/has done great things in me/Holy is his name,” in your rendering, makes my hair stand on end. This is not the victory march we usually hear in our heads when we think of Mary’s vocalizations in the Gospels. It’s more like a mantra she repeats stubbornly, sadly, desperately, but with hope of ultimate conviction.

SS: Yes, we called it the Terrified Cowgirl Magnificat.

We’ve always been drawn to Mary’s Magnificat—and felt distance from it. The language commutes to an anthem of certainty that God is gonna do all these great things and lift me up. It’s almost repulsive interpreted that way. We can’t see the teenaged mother of God experiencing it like that. She’s in the crisis moment of creation. She knows something is going to be born and something is also going to die.

But she’s also a religious child who knows her scriptures. So she’s going to lean into the covenant and tell herself again everything she knows about God. She’s a child who knows her religion and she’s just like, “God, you’re gonna have to catch me.”

Listen to “Magnificat” by Sister Sinjin here.

The Magnificat is what we hope we’re doing—imitating Mary’s fiat by saying, “yeah God, come into us and let us be fully yours, bear fruit in us. Please. And after saying yes to you maybe we’ll be so overcome by that kind of glorious world-flipping strength that we can say something like the Magnificat.”

SP: I love that. The Magnificat isn’t a triumphant anthem. It’s a leap into the breach. Talk a little more about Incarnation as Crisis. Because we’re not just talking about birthing babies here (even though that too is more fraught with crisis than we like to admit when talking about Mary); we’re also talking about making art.

SS: We really wanted to work against the curated, art-directed life, the Instagrammable life. This might be fun on social media, but it isn’t art—it’s jumping the gun. Karl Persson wrote beautifully about art, Catholic art, art in general, as wrestling with angels. If it’s art, it’s the fruit of struggle. The fruit of crisis. And the question is, what is pressed out of you at the end?

We’re called to be tenders and creators in the image of God. But when you’re doing creative work, working in eros with the desire for consummation, it can all go so terribly wrong. When you’re working in your deepest self, which is a place of union with God—there is nothing more erotic and powerful. But the closer you get to that fire, the stronger your covenant has to be to hold you.

So we think of Mary going to Elizabeth, we think of St. John of the Cross burning Teresa’s letters, and of Jacob wrestling with the angel. Struggling with God, demanding blessing, believing God honors promises. This is another way of reading the Magnificat. This is what life with God, what life as an artist, means. The artist’s fiat is to say yes to engagement with God through pain. What is created or born of that is not always lovely. But its worth is not connected to its loveliness.

***

Buy your copy of Incarnation at Band Camp.