A few years go, I was having dinner with the editor of my first two books (3 Gates of the Dead and Dark Bride) and friend, Betsy Mitchell, in Columbus, Ohio, where she was speaking at conference. What I love about Betsy is that even though she’s edited some of the biggest names in the business (Michael Chabon, Dean Koontz, Octavia Butler and Terry Brooks), she is willing to hang for a few hours with a struggling writer like myself. Plus, she’s been a great mentor as I’ve started my second career as an editor.

Having lived in Columbus for a long time, I knew just where to go for dinner: Northstar Cafe, an upscale hipster restaurant in the northern part of the city. It was a warm night for October, so we sat outside to chat about books, writing and living in New York.

After awhile, the conversation turned to Weird Fiction, Christianity and some of the inspirations for my own books. Betsy looked thoughtful for a moment and said, “Have you ever heard of Charles Williams?”

She laughed as I fan boyed all over the dinner table. I babbled about how I loved his work and how much he influenced me. Not only as a writer, but as someone deeply interested in theology. I went on about how much he was overshadowed by Tolkien and Lewis, the better-known members of the Inklings. This despite the fact that Time magazine once described Williams as “one of the most gifted and intellectual Christian writers England has produced in [the twentieth] century.”

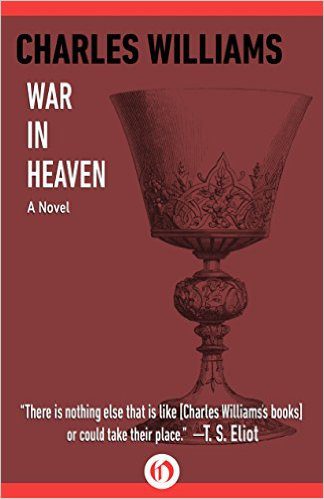

Finally, she stopped me and said, “You know, we (Open Road) just picked up the rights to republish his works. I’m editing them right now.”

I laughed and said, “Lucky.”

Pausing for a moment again, she said, “Would you like to write a foreword for one of the books?”

The words hung in the air and I’m quite sure my mouth was gaping open in shock. My brain tried to play catch up. She just asked me to write a foreword not only for my writing hero, but also for an Inkling. Me. Writing a foreword for a prominent member of one the greatest writers’ groups of all time. My brain exploded all over Northern Columbus.

Babbling my thanks, I said I’d have to think about which one I would do. She cautioned that she would have to get it approved by the Estate, but all I had to do was to write an exceptional foreword. So, no pressure, she said, smiling.

After dinner, I drove home. I don’t remember the first half of that drive very much. I was still in shock. But, as I focused, I started to grasp the magnitude of what I just agreed to do. I would be a part, (granted, a small part) of the Inklings legacy. That made me a little tense. Then, I remembered the last person to write a foreword for Charles Williams was T.S. Eliot.

Yes, THAT T.S. Eliot.

What, I wondered, did I just agree to do? How had I dared? Whatever I wrote would be awful in comparison to Eliot. Even if the estate did approve it (which I doubted), I would probably embarrass myself. For that reason, I almost backed out, but a question stopped me. How many other writers ever got this opportunity? I couldn’t pass it up. So, I emailed Betsy when I got home, telling her I would write the foreword for War in Heaven. It’s actually my second favorite Williams novel, but I wasn’t about to touch All Hallow’s Eve. That belonged to one of the greatest poets of the 20th century.

Anyway, I agonized over those 1200 words for a month. I fussed over every single word, every comma, and every phrase. Finally, I sent it to Betsy, who forwarded it to the Charles Williams Estate for approval.

A few days later, Betsy wrote me to tell me the Estate not only approved, but were excited about I wrote. After I exchanged emails with the Estate, it was a finalized deal. The book was republished a year ago, last February.

What did I learn from the whole experience? Well, I thought about Charles and the rest of the Inklings. I saw their struggles and how human they were in everything they did. Lewis never made enough money to buy proper clothes. Charles was always one step away from total bankruptcy. Tolkien wrote his stories on the back of old student exams because paper was scarce. The legends I so admired were not legends in their own time.

This point was driven home when, a few months ago, I was allowed into the Tolkien Archives at Marquette where I got to see the earliest versions of the Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. I was invited by the chief archivist to have a personal viewing of a very small section of Tolkien’s papers. It was the ultimate Tolkien geek moment. But, what really got to me, and reminded me of what I learned about Charles, was an old restaurant menu where Tolkien had scribbled a question, “Who is Trotter?” As every Tolkien geek knows, that was the original name of Strider or Aragorn, Son of Arathorn.

Tolkien didn’t know. He’d gotten stuck and had no idea who this character was. In other words, he was a human writer who shared the same struggles. So did Williams and Lewis. None of them were considered very important during their lifetime or even very highly regarded. In many circles, they were scorned.

My heroes were human. That didn’t disappoint me. On the contrary, it galvanized me and made me realize an important truth: I’d spent too much time glorifying the Inklings instead of learning from them. And, I realized, I wasn’t alone. Our obsession with the Inklings has prevented us from doing what they did, writing stories that transform people and make them think. They led a rebellion against the naturalistic worldview that smashed open the doors to people’s minds. The question is, have we, the second wave of writers, thinkers and dreamers followed them through the breach? With the exception of J.K. Rowling and Harry Potter (granted,that’s a HUGE exception), we think it’s impossible to achieve their heights, so we give up trying and settle into writing what amounts to Inkling fan fiction.

Oddly, we view the saints of the church in the same way. But, yet, we are called to be saints, to press to that kind of spiritual greatness. Whether we become famous or not misses the point entirely. We are called to “be like” the saints, not actually be them.

This, I think, is what I learned while writing a foreword for an Inkling. I learned that I should view them in the same way as I view the saints, guideposts and lamps to my own career as a writer. They are meant to guide all of us who dream of smashing the minds of materialism, gnosticism, and every other ism that infects people’s imaginations.

So, from now, on, I’m going to learn from them rather than mindlessly venerating them.

(War in Heaven, with my introduction is available from Open Road Media, today only, for 1.99)