Somewhere along the way, Christianity stopped being a faith and became a franchise.

You know the type—big budget, high stakes, clear villains, and a last-minute redemption arc. Every sermon has to feel like a movie trailer. Every testimony must build tension. And if your faith story doesn’t include a dramatic conversion and a soundtrack by Hillsong, are you even saved?

Modern American Christianity doesn’t just tell stories—it’s trapped in one. And spoiler alert: it’s not the story Jesus was telling.

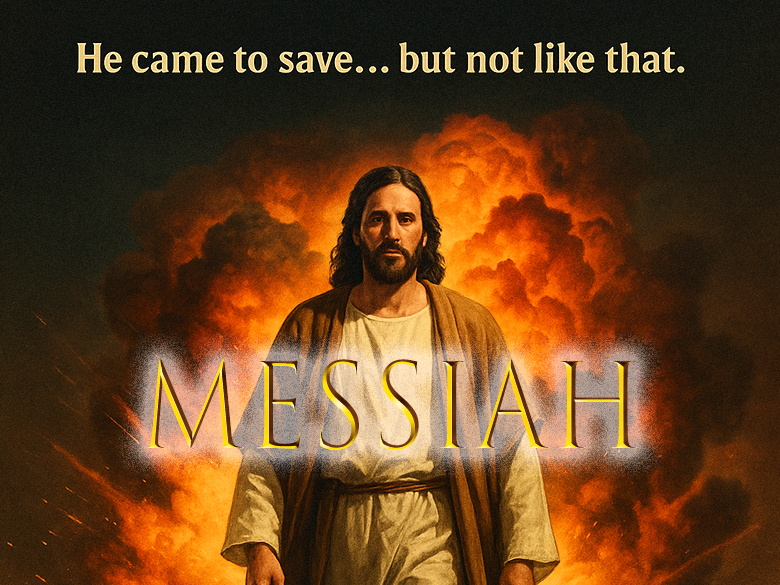

Act I: Jesus, Now With More Explosions

Let’s talk story structure. Specifically, the Western kind—the one Hollywood mainlined into our collective bloodstream. The kind where conflict is king, the protagonist must change or die, and everything builds toward a clean, satisfying resolution.

Western storytelling follows a predictable arc:

Conflict → Crisis → Climax → Resolution

It’s why every Christian conference feels like a Marvel movie with more crying and fewer capes.

This isn’t just narrative preference—it’s cultural dogma. We’ve learned to see everything through the lens of dramatic tension. You’re the main character. Sin is the villain. Jesus is the magical sidekick who dies so you can have your big moment.

That’s why testimonies are structured like elevator pitches:

- “I was broken.”

- “Then I met Jesus.”

- “Now everything is perfect (please ignore the depression and credit card debt).”

We crave narrative payoff. Resolution. Victory.

But Jesus wasn’t into tidy endings. He was into tension. Confusion. Reframing.

That’s not good storytelling… at least by our standards.

Act II: Other Stories Are Available (But Don’t Preach as Well)

Let’s step outside the Western mind for a moment. Because not every culture structures reality like a movie script.

In East Asian narratives like Kishōtenketsu, conflict isn’t even necessary. The structure goes:

Introduction → Development → Twist → Reconciliation.

No battles. No heroes. Just a shift in perspective. The point is not to conquer but to see differently.

Sound familiar? It should—Jesus used this method all the time.

“The kingdom of God is like a mustard seed…”

(Cue weird twist. Birds. Branches. No clear takeaway.)

End scene.

You’re not supposed to “win” the parable. You’re supposed to sit with it.

Other traditions, like Indigenous storytelling, African oral narratives, and ancient Hebrew cycles, all share this resistance to resolution. They focus on communal memory, balance, and the sacredness of mystery. Some don’t even end the story—they just hand it off to the next listener.

In rabbinic tradition, you don’t find answers—you find questions worthy of arguing over for generations. (Jesus was raised in this world, by the way.)

Contrast that with American Christianity, where the only acceptable form of spiritual growth is a clean three-point sermon and a fog machine.

| Narrative Tradition | Structure/Shape | Core Focus | Faith Framing | American Christianity Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western (Greco-Roman / Freytag / Hero’s Journey) | Conflict → Climax → Resolution | Triumph through personal change | Jesus as hero; sin as enemy; altar call as climax | Default setting. Testimonies become mini-movies. Everything must resolve. |

| East Asian (Kishōtenketsu) | Intro → Development → Twist → Reconciliation (no conflict required) | Reframing, perspective shift | Parables disorient to teach; truth through surprise | Often ignored or misunderstood. No villain = no traction. |

| Hebrew (Cyclical / Exile & Return) | Creation → Fall → Exile → Return → Repeat | Communal identity and memory | God’s faithfulness over human failure; rhythm over resolution | Cherry-picked. Often repackaged as personal journeys. |

| Indigenous / First Nations | Circular, seasonal, sacred storytelling | Harmony, balance, non-linear time | Wisdom from land, ancestors, and mystery | Flattened into metaphor or ignored. Doesn’t preach well in three points. |

| African Oral Traditions | Call-and-response, layered, moral balancing | Community, performance, evolving truth | Faith as shared story, not personal conquest | Appropriated in style (Black church energy) but not in substance. |

| Rabbinic / Midrashic (Jewish) | Story within story, dialogical, interpretive | Sacred tension, ongoing conversation | Scripture as invitation, not conclusion | Too messy. American faith prefers answers, not arguments. |

Different cultures tell different stories. American Christianity chose the one where it always gets to be the hero.

Act III: Why We Love Conflict (Even When It Kills Faith)

Here’s the thing: Western Christianity didn’t adopt the conflict-driven story arc by accident. It mirrors American values:

- Be the main character.

- Fight the good fight.

- Win at all costs.

- And above all else, resolve the tension.

That’s why the church has become addicted to enemies.

If there isn’t a villain—whether it’s sin, culture, the gays, the libs, or the deep state—how do you create dramatic tension?

If there’s no conflict, how do you keep people emotionally hooked and tithing?

It’s not enough to love Jesus—you need a threat level to keep the plot moving.

And if you run out of real ones? Make one up.

That’s how you end up with sermon series like “Spiritual Warfare 4: This Time, It’s Personal.”

Epilogue: The Gospel According to Jesus (Now with 90% Less Climax—Make of That What You Will)

Faith isn’t a blockbuster. It’s not a linear arc. It’s not a TED Talk with a baptism at the end.

Sometimes faith is a weird parable.

Or a cycle of exile and return.

Or a story with no ending.

Or a long, messy conversation that gets handed down like sacred gossip.

And maybe that’s the point.

Because somewhere in our craving for conflict, we lost something.

We traded mystery for certainty.

Nuance for slogans.

Communal identity for individual hero arcs.

We forgot that not knowing is sometimes the holiest place to be.

Maybe Jesus didn’t come to resolve the conflict.

Maybe he came to invite us into a different kind of story—one where we’re not the hero, not the villain, and not the audience.

Just a character, still figuring it out.

For more Snarky Faith, check out the podcast and more:

- Snarky Faith website

- Snarky Faith on Instagram: @stuartdelony

- Snarky Faith on YouTube: @snarkyfaith

- Snarky Faith on Bluesky: @snarkyfaith.bsky.social

- Snarky Faith Group on Facebook: www.facebook.com/snarkyfaith

- Snarky Faith t-shirts and mugs available here.