Double double toil and trouble/Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

Many people have heard this rhyming couplet from Macbeth, and may even recognize it as an incantation of the three Witches. We first meet these three oddities at the play’s famous opening. Entering boldly in a “desert place” featuring thunder and lightning, it’s one of Shakespeare’s most theatrical scenes in any of his plays. Later, Macbeth visits these three for some rather sketchy career advice, and it is then that these lines are recited, as they cook their magical potion.

But what are these lines about?

Actually they are about career advice. Macbeth has some rather wacky ideas about what he wants to do. He wants to be king, and honestly who doesn’t? His darling and dutiful wife is in full agreement. His visit with the witches is really about doing whatever is necessary to make happen whatever person wants.

Nowadays sociologists have developed a terminology for this yearning to “make it happen” at any cost: expressive individualism. Another word making the rounds these days is narcissism. All in all, what we’re talking about is this attitude: I want to do what I want to do. Period. And I’m going to make it happen, no matter what. Too bad the witches didn’t recite Psalm 127:1 to poor Macbeth: “Unless the LORD builds the house, its builders labor in vain.”

What to Think About on Labor Day

On this Labor Day of 2020, we should think about what we do for living—and wonder if we are “laboring in vain.” The holiday dates back to the end of the nineteenth-century, as a celebration of industrial workers. Typically, Labor Day is associated with blue-collar workers and labor unions. President Grover Cleveland signed it into law in June of 1894: this was during a time of serious unrest among American workers. We rarely think of Labor Day anymore as symbolic of workers’ rights and their inherent value, but there is a long and often bloody history of protest and justice hidden behind the symbolic “end of summer.”

Do Americans still value labor unions? I was once a member of the United Auto Workers Local # 933. I worked for General Motors, throwing steel back-and-forth at Detroit Diesel Allison in Indianapolis. Our products were transmissions and jet engines. I ran lathes, mills, drill presses, and other machinery involved in the production of engine and transmission parts. I worked in heat treat and plating departments, where vats of muriatic acid and copper cyanide solutions were used for certain kinds of treatments to the metal.

I’ve been around the block, as a blue-collar worker. And I’m proud to say it too. But I never felt called to the factory floor; I never felt like machinist was my vocation. According to CBS News, this is not so unusual: “Of the country’s approximately 100 million full-time employees, 51 percent aren’t engaged at work — meaning they feel no real connection to their jobs, and thus they tend to do the bare minimum. Another 16 percent are ‘actively disengaged.’” This means at least 2 out of 3 American workers are relatively unengaged: basically, they dislike their work. At General Motors, I was among them: I hated getting up and going to work, pretty much every single day. But the money was good for a guy my age, back in the mid-70s. So I kept showing up, and punching the clock. that is something we did back then, by the way: our time cards were punched by the clock!

Now I’m a bourgeois, effete professor in an English department, teaching undergraduate and graduate students, and doing a little writing on the side too. I’m living the dream, as they say. Still: parts of my job are sometime onerous: I dislike long meetings, I’m not very good at administrative paperwork, and I often tire easily of the warmed-over, unsurprisingly mediocre student writing that gets turned in. But generally I’ve felt like this was something I had been called to do, and as Robert Frost once famously put it, “that has made all the difference.”

Now back to those witches.

When I hear those famous words, “Double double toil and trouble,” I am reminded of all the blood, sweat, and tears that is involved in our labors. My hands still have scars dating back to my factory days. The word “labor” comes from the Latin for work, so this could just as easily be called “Work Day.” And when we work, we toil, and sometimes even find trouble. It’s hard, right? We sweat, sometimes strain, mentally and physically. Sweat, in fact, shows up in Genesis as one of the curses of our labor, due to human intransigence. Thorns and weeds, too. Oh yeah, one other small detail: the “labor” pains of childbirth (Genesis 3:16). The witches, in short, may remind us of the “curses” of work and ambition.

But today I prefer to focus on the blessings as well. As Gene Veith has written: birds do their work without anxiety. What if we can too? A spiritual approach to labor would be one capable of seeing both the blessings and the curses of work. I am a man, and as such I have never experienced labor pains or the act of giving birth. Based on my careful observation, it includes some pain and “toil and trouble,” as those witches pronounced it. However, after it’s all said and done, birth labor produces one of life’s great blessings: a child. I recall with delight the conclusion of all that howling misery. And yes, even the mothers usually end up believing all the toil was worth it.

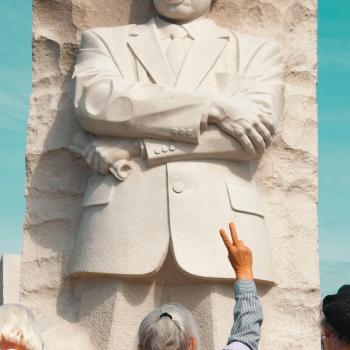

Is work and labor “worth it”? One of the best scripture verses became a common motto many years ago, and remains popular: we do not “labor in vain” (I Cor. 15:58). Abraham Lincoln gave this verse immemorial power in his greatest speech, at Gettysburg. He told us that the dead did not die in vain. A spiritual approach to labor is one that sees our work within a higher context. We labor not in vain, because ultimately there is a hope laid out before us.

Finally, one more scripture about labor. Romans 8, the apocalyptic triumph of God’s vision for all of creation, is symbolized here as a mother giving birth, groaning in labor. “We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time” (8:22). It would be hard to find a more all-encompassing passage of hope in the Bible— in this case, the metaphor is of a screaming woman giving birth. In the midst of the great lines about cosmic hope is and unforgettable comparison to labor pains and the groanings that accompany them..

Our hope, then, is that whatever our work is, we view it as somehow in concert with a Greater Work: the Labor of all of creation, groaning to become true to itself. All this is somehow attached to the building of a House; and “Unless the LORD builds the house, its builders labor in vain.” (Psalm 127:1) Thus, no need for witches, or incantations either.