The question of whether or not humans have free will is one of those venerable old questions that never gets resolved. Here, I am not attempting to come to such a resolution, only offering a brief exploration of the phenomenon of making a choice.

The question of whether or not humans have free will is one of those venerable old questions that never gets resolved. Here, I am not attempting to come to such a resolution, only offering a brief exploration of the phenomenon of making a choice.

I am writing this piece after lunch. Before lunch I made a choice to eat out, and then I made a choice of which restaurant I would eat at. I’ll use this simple example to explore some basics of making a choice.

In making my choice of a restaurant, I started by running through my mind the various restaurants within a few miles of where I live. I considered about a dozen restaurants. I held each in mind for a while as I considered if it was what I wanted. It took several minutes, but at length I decided on a Vietnamese restaurant. Why that one? I’m not sure, but the memory of its egg rolls seemed to fit my preference of the moment. I went there and was satisfied with the meal.

In the common way we use language, in choosing this restaurant I made “a free choice.” I ran a set of options through my mind and chose the one that best met my preferences. I got what I wanted. What more could one ask from a choice?

Choice and Causality

But what about causality? Examining this simple choice under the aspect of causality, a few things are readily noted. One is that the options that I ran through my mind were present in my mind because of past experience, which is to say past causality. More interestingly, though, is the question of why I have the particular preferences that I have?

I make choices based on preferences, but I do not choose my preferences. Indeed, to do so I would need another set of preferences to use in choosing the first set. And so on.

Some food preferences I have had since early childhood. Some, like a love of sweets, I share with a lot of other people. Such preferences are probably the result of my genetic make up — something I didn’t choose. Some of my preferences, like a love of Vietnamese egg rolls, came much later in life. From these considerations, I don’t think it is too wild to jump to the conclusion that preferences are something that have causal origins in our biology and are shaped by our life experiences.

To say that I chose based on my preferences is to say that I chose based on something shaped by past causality. Both ingredients in my act of choice, the menu of options I bring to mind and the preference that one of these options elicits, are the result of such causality. Although it is not directly relevant to the issue here, I have to wonder what sense there is in my saying that “I have these preferences.” As I think about how these preferences enter my decision making, it seems more accurate to say that “I am these preferences.”

Morality

But there is another level to this notion of preference. In choosing what restaurant to eat at, I was basically going with my “gut feeling,” as they say, but there was also a kind of censure acting upon this gut feeling. This internal censor was particularly concerned with the healthiness of the food that I was planning to eat. Thus I eliminated a few options that my gut would have been happy with, because of health concerns.

This sense of being torn in decision making between what appeals to us in a physical, sensual way and what appeals to our more rational, principled self is a common feeling. The gut feeling, as its name suggest, probably comes from basic biological motivations, but the censure is likely something that we have learned.

My gut absolutely loves ice cream. I would eat it a big bowl of it every day. But my internal censure says that it is not a healthy option. And since I have already had quadruple bypass surgery for clogged arteries, I have a first hand understanding of the negative consequences of letting my gut have its way.

The point of this is that when we talk of preferences, we aren’t necessarily talking about a singular thing, but of a kind of conflict. Human morality, on the whole, is about developing a habit of making choices based on moral or rational principles rather than on the gut. (Though I personally think that if we lose all contact with the gut, if we become too rational in our choices, we also lose something of our humanness.) Some might argue that it is only the choice made from such rational principles that constitute free choice. A choice made simply on our inclinations, our preferences, is not free at all. But this too is questionable.

Moral Software

I have spent a lot of time in meditation observing within myself the conflict between sensual inclinations and rationality-based principles. It’s rather fascinating. It would seem that we have two quite different sets of motivations at play. The one, as mentioned earlier, likely has deep biological roots. Geneticists claim that some of our behavior related to eating and sexuality comes from a part of the brain that is formed by genes that go back to the time of the dinosaurs or earlier. These inclinations certainly feel rather deep and primitive.

What I have called “the censor,” has a very different feel to it. From a naturalistic point of view we must assume that it too is a part of the neural mechanism of the brain, and to that extent has a genetic origin. But clearly this part of the brain operates on information that we have learned or experienced.

Perhaps the neural mechanism involved in making moral decisions is like a computer: there is some neural “hardware” in the brain that has its origin in our genes, though it evolved rather late in our evolution; but it requires some “software,” some learning, in order to function effectively. And if this is so, I would further suggest that not only do we have to learn how to make these “moral” choices, but our skill in making such choices needs to be reinforced. In making such choices we develop the habit of making choices – we develop a habit of living intentionally. As a matter of speculation, I think it worth considering that the function of religion through the ages has been as a repository of, and to provide education on, such “moral software.”

Choices that include such learned behavior are certainly different from simple biological determinism, but are they free from a more complex forms of determinism? Learning is dependent on past experience, which is to say past causality, so causality is involved in learned behavior also.

Summary

As I stated at the beginning, my goal here is to explore what happens when we make a choice, not to settle the question about free will. The simple example provided, I think, suggests the following: to select from a set of options the one that best meets our immediate preferences gives a feeling of freedom. To select based on a learned set of principles gives a different sense of freedom. But if we push the context of our choices out far enough, we certainly cannot deny that such choices might be completely shaped by past casualty, though it is also the case that we can’t prove this.

In any event, to live intentionally requires that we have a clear image of how we want our life to unfold, that we have some end in mind; further, it requires that we make choices consistent with progress toward this envisioned life. To live intentionally it is only important that we make such choices; we don’t need to understanding how it is that we can make choices or what exactly the “I” that makes such choices actually is. My experience has repeatedly demonstrated to me that living intentionally in this way leads to a higher quality life. And I definitely prefer to live as high a quality life as I can.

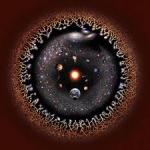

But I think it is also good to understand that there is not some little person inside us that is independently making these choices — to understand that even the simple choices we make are the result of webs of causality that likely can be traced back to the time of dinosaurs and earlier. Our being is contingent on these webs of causality. We are so connected with the rest of the Universe that we cannot make a simple decision about where to eat lunch without involving such ancient and far-flung causality.