Psycho and Guilt

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 masterpiece, Psycho, is another one of those films that you simply cannot have spoiled. Do yourself a favor and check it out (it’s on Netflix as of this publishing), and then come right back here.

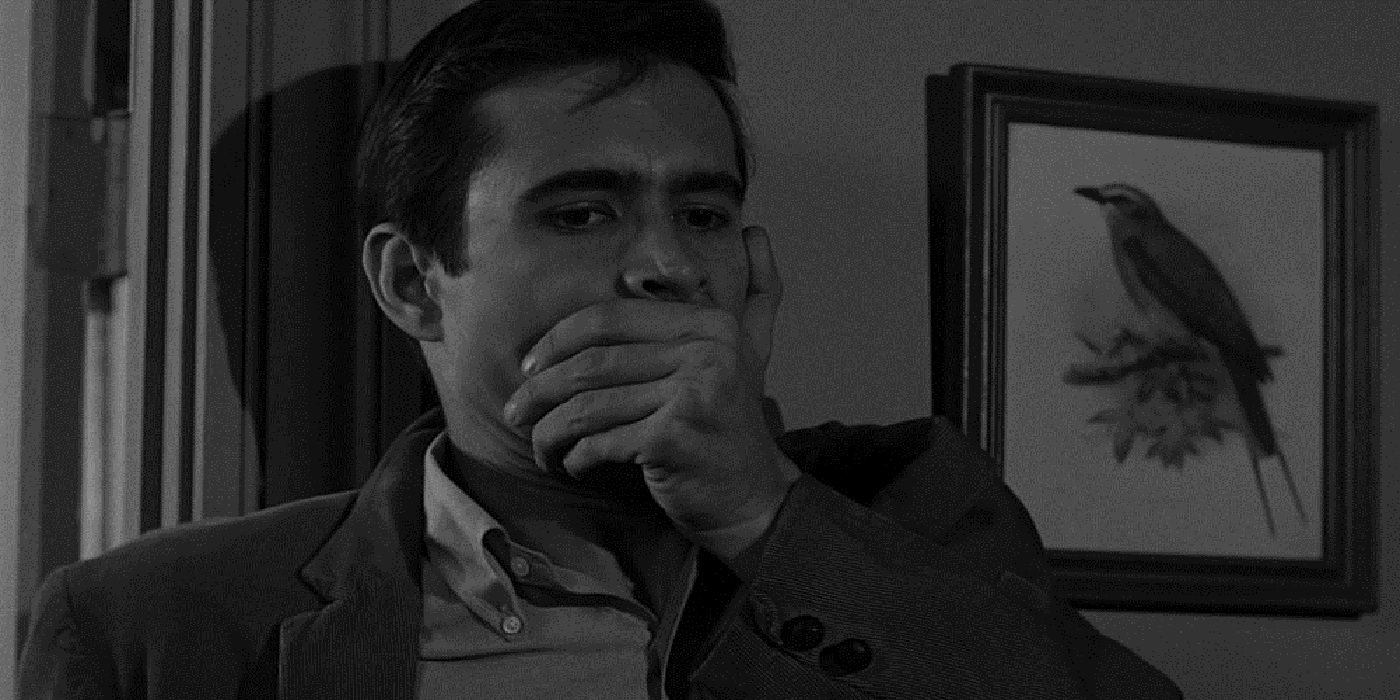

This twisted horror movie follows Marion Crane on the run after embezzling $40,000 from her boss. She does this hoping she can settle the debts of her boyfriend so they can finally get married, but she is quickly beset by her inescapable guilt over the matter. Marion allows herself to regroup at the Bates Motel in the company of Norman Bates, who maintains the motel with his invalid mother. But while showering, Marion is violently attacked by an unseen figure, whom we are led to believe is Mrs. Bates. Norman then plays the role of the good son and hides his mother’s crime by disposing of the body.

Days later, Marion’s sister, Lila works with Sam to try to find out what happened to her. They work with an investigator who tracks Marion to the Bates Motel before “Mother” takes him out. Lila and Sam take matters into their own hands and visit the motel themselves, determined to get some answers from this Mrs. Bates once and for all. What they find there, though … nah. I’ll let you find out.

The Commonplace Nature of Sin

Part of the tragedy of this whole thing is that there remains a bit of purity to Marion that makes us root for her, even as her breach spurs the film’s entire line of action. She is devoted to her relationship with Sam even though the connection is not easy to maintain. And she is able to feel a measure of sympathy for someone like Norman. And yet such a person is still capable of wrongdoing. We are with Marion step-by-step as she carries out her decision to abscond with $40,000. The film positions us to become invested in Marion getting away with this. This is where the film begins to expose us to the commonplace nature of sin.

But it’s not just “sin” that this movie tracks, but the shame that it engenders. Maybe we all can break the law, temporal or celestial, but none of us can evade the feelings of guilt that follow, and what arise in its wake can make a bad situation much worse. In Norman’s case, that path of sin very quickly ballooned into something nightmarish. He makes the connection about each of us being stuck in our own traps, to which Marion replies that she stepped into hers. We understand this as meaning she has built a cage for herself in choosing to break the law. Marion makes the choice to try atoning for her mistake, but she never gets the chance.

A Device for Voyeurism

There are further layers of twistedness to the infamous murder scene. It’s obviously disturbing for how physically vulnerable she is in the shower. But immediately before the murder, Marion reveals that she has decided to return back and pay the piper. In the context of Marion’s repentance process, Marion cleansing herself in the shower represents her washing away her transgression, making proper restitutions for her sin. And it is here in the middle of this purification that Marion is killed.

There are additional cinematic devices the film uses to force us to confront our own capacity for evil. Your Film 101 class, for example, probably mentioned the moment where we see Norman peeking at Marion as she’s undressing, and the film forces us to take his perspective, revealing the whole cinematic apparatus as a device for voyeurism. And didn’t most of us put this movie on because we were just in the mood to watch someone get some stabby-stabbies anyways?

As with Marion’s infraction, we are basically holding hands with Norman as he acts his 37-point plan to cover his sin. There is a protracted sequence in which we watch Norman clean up the scene of the murder, physically move Marion’s body, drive her car out to the swamp, and sink the whole thing in an effort to ensure his getaway. And yet, because we have already spent the last hour complicit in some wrongdoing, this pivot is all too natural. We have become very good at identifying with wickedness.

After grilling Marion for an hour over her transgression, the film basically turns the tables in the scene where “Mother” stabs her to death in the shower. We aren’t in a position to pass judgment on Marion anymore. Her actions have been answered with the ultimate penalty. What’s more, our whole meter for evil has suddenly blown up to new proportions. Maybe there are far worse acts of evil than embezzling from your (rich, arrogant, salacious) boss.

The matter of the missing $40,ooo dollars basically gets thrown out the window by the end–who cares by that point? By the time we’re done, we have witnessed not only just how deep and dark the abyss is, but our own proximity to its inescapable pull …

Anyways, happy trails, everyone.