The title of this article may be misleading. A more accurate rendition would be “The seven last phrases (or sayings) of Christ.” Questions of semantics aside, the seven last words refer to the final statements of Christ leading up to His death.

As one would expect, the words spoken by Christ have been the subject of study and speculation for two thousand years, and “the seven last words” are no exception. In this article, I will review each of the sayings and seek to place them within a broader context in accordance with Catholic theology.

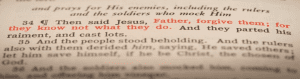

“Father, forgive them; they know not what they do.”

In commencing the Jubilee Year of Mercy, Pope Francis issued a Bull of Indiction titled Misericordiae Vultus (the face of mercy). In the document, Pope Francis wrote, “Jesus Christ is the face of the Father’s [i.e., God the Father] mercy.”

This truth is evidenced in Jesus’ words as they are recorded in Luke’s Gospel. “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” (Luke 23:34). The depth and magnitude of Christ’s mercy are underscored when one considers that He is asking God the Father to forgive those who were executing Him.

In a sense, Christ’s prayer for forgiveness can be extended to all humanity. Since all have sinned (Romans 3:23) and since the punishment for sin is death (Romans 6:23), and since Jesus took upon Himself our sins (2 Corinthians 5:21), it must be that all who have sinned share some responsibility for the death of Jesus.

Additionally, Jesus’ words ought to inspire how we treat one another. As God has pity on human misery and desires not to punish human beings for their sins severely, so human beings are to have mercy on their fellow humans.

“Amen, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

When this saying of Jesus is taken in isolation, it appears unequivocal and uncomplicated;

however, it is quite layered.

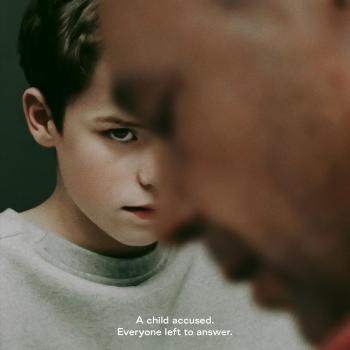

As anyone familiar with the Scriptural accounts of the Crucifixion knows, Jesus was crucified between two criminals. One of the criminals is unrepentant. The other man, however, admits his guilt and seeks pardon from Christ, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” (See Luke 23:39-43).

The saying of Jesus, directed to the “penitent thief,” has been used to attack the Catholic Church’s teaching that baptism is necessary for salvation. While Scripture is silent on the subject, it is thought that the “penitent thief” was not baptized. Yet, Jesus assures him that he will obtain entry into Heaven (“paradise”). How, then, was the “penitent thief” saved?

First, it must be pointed out that the necessity of baptism for salvation is not a Catholic Church creation. Rather, the Church follows Jesus’ teaching, “Amen, amen, I say to you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and Spirit.” (See John 3:5). The answer of how the “penitent thief” was saved is found by understanding the various forms that baptism may take.

The Catholic Church recognizes three types of baptism, one of which is called the baptism of desire. Contained within the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Church, baptism of desire is described as inclusive of “Those who through no fault of their own, do not know the Gospel of Christ or His Church, but who nevertheless seek God with a sincere heart, and, moved by grace, try in their actions to do His will as they know it through the dictate of their conscience – those too may achieve eternal salvation.”

In applying the standard provided by the Second Vatican Council to the “penitent thief,” one sees how his salvation was made possible.

“Woman, behold, your son.” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother.”

Jesus gifts humanity His flesh and blood as spiritual food. He gives His life for our salvation. And He gives His mother to be our mother, the mother of the Church.

If the Catholic Church is the mystical body of Christ and if Mary is the mother of Jesus, then it is no inferential leap to consider Mary as the mother of the Catholic Church.

“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Of the seven last statements of Christ, this one is perhaps the most complicated and misunderstood. After all, if Jesus is the Son of God and a sharer in the Divine essence, how is it possible that God has forsaken Him?

In a sense, Catholicism is built upon a Jewish foundation, and it is an error to deracinate Jesus from the messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. Therefore, Jesus’ question ought to be examined under two aspects.

First, it should be observed that Jesus is quoting from the first line of Psalm 22. In doing so, He is showing that He is the suffering servant that bore the sins of humanity. Taken in this context, we see Jesus’ words as the fulfillment of prophecy.

The second aspect to consider is the devasting effects of sin. As Saint Paul observed, Jesus became sin. That is to say, Jesus took upon Himself the sins committed by human beings and suffered the punishment for our sins. (See 2 Corinthians 5:21). Since sin separates us from God, so Jesus, in becoming sin, felt that separation in His human nature.

“I thirst.”

While composed of only two words, this saying of Jesus contains some ambiguity. As such, it is subject to several interpretations.

In one sense, one can read this statement in a perfunctory way, dismissing them as words spoken by a dying man. However, a theological reading of the text (John 19:28) suggests other possible interpretations.

One can read Jesus’ words in light of Matthew 26:29, “I tell you, I will not drink from this fruit of the vine from now on until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.” In this context, Jesus confirms that He is returning to the Father, thus making His words in Matthew 26:29 a prophecy.

Similarly, “I thirst” can be understood as the fulfillment of the messianic prophecy of Psalm 69:21. An interpretation that takes both verses (Psalm 69:21 and Matthew 26:29) together would add evidence to Jesus being the Messiah.

“It is finished.”

This saying suggests the completion of the work Jesus came to complete. Translated from Latin, the statement is indicative of a debt being paid in full. That debt, the cost incurred by humanity for our sins, has been satisfied through the work and death of Christ on the Cross.

“Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.”

With these words, we have the whole of the work of Christ and the purpose of life itself. The ultimate meaning of life is found when we place ourselves in the hands of God.

In giving Himself up for us, Jesus has reconciled man and God. It is through Jesus that we are conformed to the will of God.

Conclusion

Catholicism asserts that God became a human being in the person of Jesus. If that is true, then the words spoken by Jesus are of immense importance.

In this paper, I have sought to examine “The Seven Last Words” of Jesus and explain their significance.