The earth has thawed, and I am removing ground covers to reveal the loamy soil beneath, where tiny organisms have worked through the months going about their business of living, unaware that they are doing me the service of preparing my garden beds. In a good organic garden, one has occasion to interact with many interconnected eco-systems. Soil is not so much a substance as a civilization, or even a network of civilizations. Scientists suspect that we have identified only 1 % of the organisms that make up a healthy soil structure. In one cup of undisturbed soil may be found as many as 200 billion bacteria, 20 million protozoa, 100,000 nematodes.

Larger organisms, visible to the eye, such as earthworms, insects, and spiders, are also beneficial to the soil’s eco-systems. And so gardening means a constant encounter with beings we’ve been trained to regard as disgusting, things we don’t want to touch. Lift a cabbage leaf and find a spider; turn the compost and find giant earthworms pinkly clinging. It’s impossible to be too fastidious abut sharing space with creeping things, if one spends the day in the garden.

Our loathing of the disgustingness of most other living things leads us to make war on our environment simply for the sake of cleanliness and tidiness. Our concept of a “clean” environment ought to be of an environment uncontaminated by killing pollutants, but when we clean our homes we arm ourselves with an array of chemicals designed to destroy organisms. The American perfect lawn is only made possible by the strategic blasting to death of anything in it except grass.

But all of this is futile, since these organisms are sharing body space with us, already. The most recent scientific estimate is that the average human body contains approximately 40 trillion bacteria – nearly as many as the number of human cells making up our bodies. We are walking kingdoms of micro-organisms.

Our fastidiousness about tiny, disgusting, alien living things is a denial of our own bodily nature, of the slime and mess of matter. Deeply rooted in our philosophical tradition is a suspicion and loathing of this base matter, and this has repeated itself over the ages from the Platonic denigration of the body to the many heresies of spiritual purity to the contemporary obsession with cleanliness, not only in our houses but in our persons. Ideals of human beauty demand bodies pared to near-deathly thinness, bodies removed of hair, genitals bleached. Sex is often considered “dirty” – and, indeed, it is a messy, disgusting business. But the trite meaningless sex celebrated by popular culture is sanitized, clean, empty, unreal. Even celebrations of childbirth present clean white images, but the activity of childbirth is all about mess, blood, amniotic fluid. Sometimes there is piss, shit, and vomit. Sometimes the body is torn. It’s not clean. Eating isn’t clean; digestion isn’t clean. To be human is to be disgusting. And as we grow older, all efforts to imagine otherwise fail, as our skin wrinkles and grows blotchy, our teeth yellow and fall out, our flesh bulges and sags. Then eventually we die, and decompose.

To make peace with death is to make peace not with purity and emptiness, but with the disgusting. There are forms of piety that turn away from all things dirty or disgusting, emphasizing purity and emptiness, but these pieties are foreign to the Christian worship of Christ incarnate, Christ born of woman, Christ with a human body all organs and fluids, Christ bleeding on the cross. And thus, it is not permitted that we should turn away from another human because he is disgusting, or because she is dirty. Religious art of the middle ages, the grotesques on illuminations and the gargoyles on cathedrals teach us to find love amidst the lineaments of ugliness, not to seek only for the pure or perfect beauty. This is what happens in human love, as well, as we see in the blotches and deformities and imperfections of another body the unique being who is irreplaceable for us, and we don’t cease to love this body because it shits and farts and sweats and oozes and grows old and dies and is eaten. Is there in creation’s feeding on itself, in this constant dying and giving of life, a sacramental hint of the Eucharist? Christ consents again to become one of us, to go a progress through the intimate and disgusting recesses of our bodies. In death we are in life; the vile is the glorious.

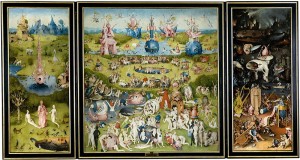

(image credit: Hieronymous Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500-1505. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:El_jard%C3%ADn_de_las_Delicias,_de_El_Bosco.jpg. Public domain in the United States)