It is the day on which nothing, apparently, happens.

This nothingness, this emptiness, is sometimes worse than the passion of grief or the melancholy of mourning. It is a kind of erasure, all meaning lost, a blank beige wall looming up against the sky. God is dead. Perhaps there never was a God. Perhaps nothing ever happened, ever, and there has only been this deadness, this emptiness, the blank beige wall. Maybe four blank beige walls. Maybe you are trapped.

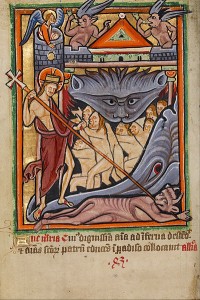

Jesus has descended to the dead. I imagine this in a kind of absence of philosophical sophistication, turning instead to the mythic and epic tradition of wayfaring heroes: Herakles, Orpheus, Odysseos, Aeneas. I imagine the thin skin of the earth falling away and the shadowy depths awaiting. The hero goes down alone. Up above, people go on living, but do they hear, from time to time, the wailing of the lost in the shadows below, or the rending of walls and prisons? Is there an uneasy clamor? Herakles managed to rescue and bring back Alkestis, but Orpheus failed to reclaim his lost Eurydike. So difficult it is, to wrest back from the shadows one who has passed. Odysseos traveled among the shades to hear the prophecies of Tiresias, Aeneas to get advice from his father. In all of these cases the central point of the descent to the underworld is that it is part of the hero’s journey. The purpose of the journey is that the hero may become a hero – he (and I do not use lightly this masculine pronoun, because the epic heroes have always enjoyed the privilege of the male, the privilege to enter and penetrate the dark spaces) must face his fears and discover his destiny, before he can emerge to find his path. Think of Luke Skywalker entering the cave on Dagobah.

Joseph Campbell says: “We’re not on our journey to save the world but to save ourselves. But in doing that you save the world.”

This suggests a hero who has both the power to save himself, and the need to be saved. I’m not sure such a hero ever existed. The great heroes of myth work always with the help of the gods, who deign to take an interest in them, because of their epic stature. It is true, however, that for the heroes of old the salvation of the self is central to the story: Odysseos needs to reclaim himself in order to win his homecoming; Aeneas needs to forsake his old identity and gain a new one, in order to found the destined Rome. In facing the darkness they come into their own as heroes. On the surface of the story, all is now well. But beneath the surface we find hints of trouble: can Odysseos ever truly go home again? Is Rome worth the violence enacted in its birth? The Death Star always is rebuilt. A new Dark Lord always rises. I think of the cyclical pattern in Stephen King’s Dark Tower series: does the hero make the same mistakes over and over and over, for infinity, losing all he loves in his insane quest to achieve his totem?

The Christian myth touches on this heroic motif of the journey and descent, but with a difference. Jesus has no need to save himself, or to become himself. The purpose of the descent of Jesus to the underworld is entirely for the sake of saving others – saving the world.

This is difficult to remember or even to believe on the day when nothing happens, the day of the four beige walls. But there is solace in knowing that Christ descended even to the dead to bring about the world’s salvation.

(image: The Harrowing of Hell, Anonymous – credit: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harrowing_of_Hell_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)