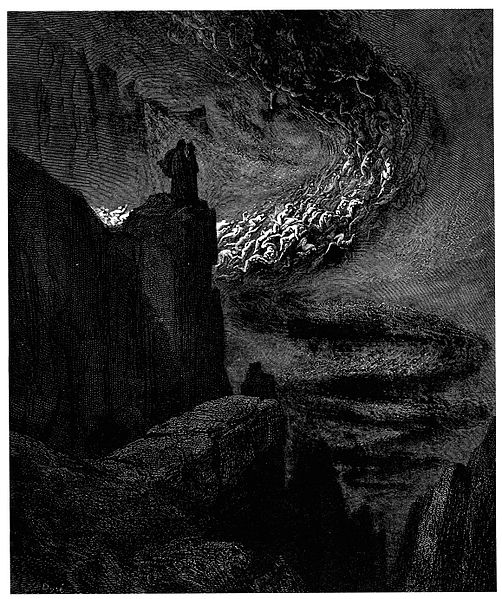

In Canto 3 of Dante’s Inferno, the pilgrim arrives at the brink of Hell, and encounters the shades of the lukewarm or indifferent: those who, in life, never chose a side, or took a stand, and now are condemned to rush round and round after a blank banner.

“So many, I had not thought death had undone so many,” the poet writes – and five hundred years later these words would be echoed by another poet, T.S. Eliot, describing London crowds in The Waste Land. Eliot’s darkest work is part of his early “infernal” phase in which the characters seem to move through dreamlike, foggy urban hellscapes, repeating endless and mindless patterns, on futile quests that have no goal.

In a poem just a little bit earlier, Eliot presented us with the memorable-for-being-unmemorable J. Alfred Prufrock, a damned soul who takes all the sexiness out of damnation. Prufrock wanders through the “muttering retreats” of that same London, with the evening spread out against the sky above him “like a patient etherized upon a table.” Paralysis, amnesia, and stagnation are themes in Prufrock. The protagonist sees himself as an insect pinned and wriggling, as one who might as well be dead already. He sees himself grown old, walking the beach, where the mermaids do not sing to him. Like one of the hollow men from another infernal Eliot poem, and like Dante’s damned, Prufrock is condemned to go round and round, to the same tea parties, hearing the same voices – but never the ones he wishes to hear. These characters drift through a dreary inferno in which the end of the world comes not with a bang but a whimper, where the cycles of history draw us through the same empty patterns.

Dante’s portrayal of the lukewarm and uncommitted is alluded to by another but very different Anglican writer of the same period: C.S. Lewis, at the end of The Last Battle, portrays one group of dwarves as refusing to take sides, but rather egging both the Narnians and their enemies on to destroy one another, even entering into the killing from time to time, to keep things even. “The Dwarves for the Dwarves.” The scene in which they shoot all the talking horses still makes me angry and sad, even if it didn’t really happen. Never kill a talking horse.

The dwarves who refuse to take sides find themselves in their own dim liminal inferno, too, trapped forever in their minds in a dark stable with no light or clean water or room to move, a physical space that images the spiritual space they occupy, a space without magnanimity or generosity or daring – even if, in reality, or if they were to shift their mental space, they would find themselves in a green and luxurious paradise.

I’ve been thinking of these stories and images a lot lately, because I keep encountering so many people who take pride in their refusal to take sides, in their commitment to the “pox on both their houses!” narrative. Like the dwarves, they seem content to sit on the sidelines, hoping that Left and Right will destroy one another. “Both sides are bad,” they say.

And for many years I was in that camp. I’m not a joiner. I distrust slogans, and loathe culture wars. I have been a registered independent for most of my voting years, and up until recently just sort of hoped the Democrats and Republicans would destroy one another. I still do think that loyalty to a political ideology or side can be dangerous, and that “taking sides” shouldn’t usually mean signing onto a political team.

Look what happened to the Republicans, after all. Two years ago, I thought that the prospect of Trump as a candidate would be a challenge to blind party loyalty – but, no. Many seemed to think they had to support anyone the party elected. And so they did. And contrary to their assertions, they did not proceed to correct and control Trump, but rather to defend his every word and deed, so that they quickly morphed into his toadies and bootlickers. So by now, whatever one may think of the Democrats, the Republicans have become the party one must stand against, if one cares about ethics and human decency.

It is no longer morally reasonable to say “both sides are equally bad,” when one side is stripping the land of its protection, cutting away safety nets, rejecting principles of human dignity, and now kidnapping infants and keeping them in cages. It’s not about Democrats vs. Republicans anymore, nor Left vs. Right. You might be a progressive liberal, or a radical leftist, or a paleo-conservative, or an anarchist, or eschew labels wholly. Whatever you are, this is one of those times in history in which refusing to take a stand gets one lumped in, not with an Aristotelian “golden mean,” but with Dante’s too-bland-even-for-hell-to-want.

I’ve been thinking of another character who didn’t want to take sides: Treebeard, from The Lord of The Rings, tells the Hobbits that he is not altogether on anyone’s side, because no one is altogether on his. I know how he feels…well, a little bit, since I’m not a tree-herd, exactly. But I know what it is to feel that no one in power has one’s well-being truly in mind. As a tree-herd, Treebeard sees that in the wars among elves, dwarves, orcs, and men, nature itself is often the most devastated victim. The “Brown Lands” have never recovered from the war in which Sauron was first defeated. The Entwives are gone forever. The “good guys” are not, after all, especially good. They just happen to be trying to stop the spread of annihilating evil.

Treebeard sees which powers are devoted to senseless destruction, and even if he doesn’t exactly join up with the armies allying against Sauron, he knows which side is is “altogether not on.” And he rises up against it, not because of a lust for destruction or love of violence or adulation of power, but simply to protect what he knows to be good.

T.S. Eliot’s diagnosis of the sickness of modernity had to do with an enervation, and emptiness, masked sometimes as bourgeois respectability. Just a few years after The Waste Land, this sickness would erupt into a widespread spiritual and ethical plague, as fascism began to rise in Europe – and the nice people did nothing about it. Who is Prufrock to struggle with a demon, after all? Even a shabby demon, like the one in Crime and Punishment? We’re post-modern, now, and not modern anymore, supposedly, but the sickness continues. Maybe it’s really a sickness of humanity, the moral sloth or apathy once termed “acedia” by the old moralists.

There are times when sitting on the sidelines and taking a middle ground are no longer virtuous options, and this is one of those times. Don’t be a nameless dead soul running around after a blank banner on the outskirts of hell. Don’t be Prufrock. Be Treebeard.

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gustave_Dor%C3%A9_-_Dante_Alighieri_-_Inferno_-_Plate_14_(Canto_V_-_The_hurricane_of_souls).jpg