Note: I wrote this essay a number of years ago, but am mindful of its relevance as we consider the Antonin Scalia legacy in the aftermath of his death, a task that remains especially vital as more than three years Mitch McConnell and Donald Trump have reshaped the entire federal judiciary in his image (including, of course, the Supreme Court). Yesterday, Donald Trump also announced his intention to nominate Scalia’s son Eugene, also an attorney, to replace Alexander Acosta as Labor Secretary.

Legal conservatives lionize Scalia. However, his impact on American jurisprudence and American society has been toxic, perhaps irredeemably so. Scalia’s medieval religious views and equally hidebound perspective on Constitutional Law epitomize what one might call an ontological fundamentalism that quite suddenly runs rampant in American political thought these days.

Here’s the essay, with some updates.

_____

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia once remarked in a dissent that many dangers visit the Court in sheep’s clothing, “but this wolf comes as a wolf.” So too with Scalia.

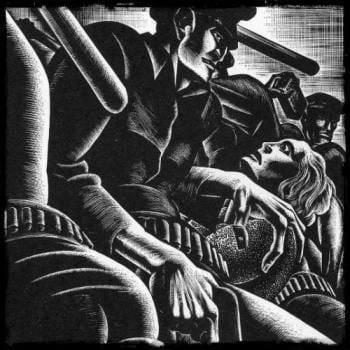

We can attribute much of the contemporary sclerosis in national government to the crouching wolf at the door, the successful arrival on the national stage of the legal conservative movement. In the last 30 years — lovingly midwifed by the Federalist Society and lavishly sustained by frankly astonishing levels of financial support from conservative foundations, think tanks, and business associations — legal conservatives have steadily assumed more power and influence in public life. All the while black-cloaking their political agenda behind allegedly non-political, purely intellectual commitments to the original meaning of foundation legal documents, particularly the Constitution. All the while bleating like sheep about their beleaguered position at law schools and on the bench.

But Scalia, their champion, cannot help himself. He opens his robe. Inside he is all wolf.

Court Jester

Scalia swaggers. He intimidates. He’s Nino! Colorful, quotable, and charismatic. Brilliant and hard-working. Voluble and entertaining. Irrepressible and fearless. He can do it all. He writes. He hunts. He sires nine children. His words are swords, ambuscades of righteous religiosity aimed at the nation’s legal and moral deviants, its corrupt parasitic entrails. He is a lawyer’s lawyer. He could argue either side of a case and win. The liberals love him. He’s so charming and amusing. He disarms them. They fear him. His withering diatribes and clever insults.

Scalia is the Court Jester. His influence, however, also illustrates how legal conservatives have seized the palisades of American constitutional theory. Conservatives of all stripes – libertarians, advocates of judicial restraint, federalists, Christian conservatives, law & economics partisans, executive power hawks – have set aside their differences to present a united front on the infallibility of the Constitution. Their methods – originalism and textualism – have become their madness. Scalia contains within himself and symbolizes their unity of vision and purpose. Nothing less than the full recalibration of American political life. A two-pronged strategy. Control the courts. Seize legislative majorities. Limit the scope of judicial activity to preserve the political primacy of state and national legislatures.

Jesuitical Casuistry

With six Roman Catholics on the Supreme Court, with five of them (Scalia, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, John Roberts and Anthony Kennedy) theologically and intellectually and politically conservative as only well-educated Catholics can be, it is not unfair to characterize the legal conservative movement led by these justices as medieval in its intentions and Jesuitical in its methods. Here is where Scalia the wolf can instruct us on the impact of the broader flock of sheep in this legal movement, who are neither so brave nor so honest as Scalia in their self-justifications.

Scalia frankly attests to his opinions. “I’m a law-and-order guy. I mean, I confess I’m a social conservative, but it does not affect my views on cases.“

Well, who knows if his opinions do or do not affect his legal judgments? It does not matter, because the brilliance of Constitutional originalism and textualist exegesis is that SCOTUS conservatives will generally achieve the political outcomes they want simply by punting tough policy issues back to the legislative bodies.

So yes, there is some Jesuitical casuistry at play here, and Scalia (who was first in class at his Jesuit high school and Jesuit college), Clarence Thomas (graduate of a Jesuit college), and other leading judicial conservatives are entirely mindful that their formal methods and substantive goals harmonize. Scalia frequently cites his commitment to the First Amendment as proof that he does not hew to a doctrinal line. He supports the free speech of flag burners! But this commitment is the exception that proves the rule, for Scalia also supports the free speech rights of abortion clinic protesters and corporate campaign contributors. The active component of his commitment may be less to the First Amendment itself as a principle, and more to the character of those whose interests advance under the protection of the First Amendment.

Not surprisingly, Scalia could not conceal his wolfishness when he declared at the inaugural meeting of the Federalist Society in 1982 that among the Founders he preferred Alexander Hamilton, the sexy bad boy of the Constitutional Convention, to its nerdy goody-goody, James Madison. Indeed, despite some disingenuous protestations to the contrary, legal conservatives generally love the vigorous, independent executive first envisioned by Hamilton, an executive that projects its power far and wide, and does not concern itself overly much with trivialities such as human rights, international law, legal transparency, and the more inconvenient amendments to the Constitution (we might appropriately consider SCOTUS conservatives to be the rightful inheritors of the philosophically conceived political realism originating with 13th-century Scottish philosopher Duns Scotus).

Scalia’s Sheep

The Federalist Society is Scalia writ large and small. Writ large because the Federalist Society is the organizational expression of the legal conservative commitment, theologically conceived, to anchoring political life in the original, infallible meaning of the U.S. Constitution, which is their communion chalice, their Bible, their ark of the covenant. Writ small because the Federalist Society members, from founder Steven Calabresi to political philosophers such as Charles Kesler, all gripped with a perpetual sense of aggrievement, mewl incessantly about liberal elites and an activist judiciary, while shamelessly (wolfishly) advancing their own profoundly reactionary intellectual agenda.

The Federalist Society initially conceived itself as a political alternative within law schools to the activist National Lawyers Guild, a bête noir of conservatives since its establishment in the 1930s. Truly, the comparisons now ring hollow. In 2017, the Federalist Society, with more than 200 chapters at U.S. law schools and more than 70,000 practicing attorneys in 90 cities, reported revenues approaching $21 million and more than $28 million in net assets. Donors include libertarian industrialists, including the Koch brothers, Richard Mellon Scaife’s foundation and the Mercer family. By contrast, the National Lawyers Guild, with 5,000 members, and which has never benefited from the largesse of the wealthy and powerful, in 2016 reported only $712,000 in revenue, and merely $205,000 in net assets.

Progressive lawyers founded the American Constitution Society in 2001 following the disputed 2000 presidential election in which the Supreme Court, with dubious logic, handed the presidency to George W. Bush. The ACS claims to have 200 law school and practicing attorney chapters. In its most recent disclosures, for 2016, the ACS reported nearly $6 million in revenue and more than $5 million in net assets. A recent Politico article by Evan Mandery does a great job sussing out the differences between the Federalist Society and the ACS and explaining why legal conservatives have been so much more successful at building institutions that wraps around their ideas than legal progressives.

Leo Strauss and the Esoteric Method

Legal conservatism shelters under its umbrella a diverse set of intellectual approaches and philosophical commitments. Similarly, originalist and textualist methods derive from a range of intellectual traditions centered around a few key academic institutions: the University of Chicago, the Claremont Institute, and more indirectly Princeton University, Harvard University, the Hoover Institution, UCLA and George Mason University. Intellectual godfathers include political philosophers such as Leo Strauss, Allan Bloom, Harvey Mansfield, and Harry Jaffa, all of whom have employed a species of magical thinking about foundation political texts in the Western philosophical canon, beginning with Plato and extending to Nietzsche. These classically trained philosophers — often categorized as Straussians — have also branched their carefully constructed tree of canonical works of Western political philosophy to encompass both European and American political thought. Straussian students of political philosophy have done much to vitalize the thoughts and writings of the founding fathers of the United States and Abraham Lincoln.

The “esoteric” method pioneered by Leo Strauss borrows heavily from medieval Church philosophers such as Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus, and burrows deeply into the meaning of foundation philosophical texts, which because of the conviction that they contain timeless truths about human nature and human relationships, obviate any need for historical situation. Straussians privilege text over context and universal truth over the thread of history, largely because historical and narrative understandings can lead to moral relativism. Additionally, Leo Strauss’s efforts to elucidate the influence of Plato through the course of the Middle Ages led him to the conclusion that the most precious truths contained in the Western philosophical canon were secret and encoded, and could only reveal themselves to the initiated acolyte or the most subtle student.

Legal conservatives have to some degree reaped the rewards of the spade work done by this older generation of academic political philosophers. The precepts of Originalism and Textualism with regard to constitutional studies reinforce the Straussian focus on foundation texts, hidden or subtle meanings, an ahistorical valorization of frozen language possessing timeless universality, and a morally driven concern for the dissipation associated with values relativism.

The legal conservative method, of course, leads otherwise very bright people deep into the darkened logical caves associated with biblical fundamentalism, in which scriptural exegetes hyperscrutinize sacred texts to locate hidden meanings anchored to divinely authored truths. Legal conservatives will writhe around the unanswerable and possibly irrelevant question: What did this clause of the Constitution mean to the Founders? One might reasonably ask in return: Why not closely inspect entrails?

You Think There Ought To Be A Right To An Abortion? No Problem.

Well, actually, there is a problem. Justice Scalia asks and answers this question rhetorically by way of his capsule summation of Originalism and Textualism. Scalia’s answer being: “The Constitution says nothing about it. Create it the way most rights are created in a democratic society. Pass a law. And that law, unlike a Constitutional right to abortion created by a court, can compromise. A Constitution is not meant to facilitate change. It is meant to impede change, to make it difficult to change.“

The problem is this. Legal conservatives attach a meta-meaning to the Constitution (it is designed to impede change), along with particular interpretations of its clauses, that elevate the importance of old-fashioned politics for securing non-universal rights (versus judicial remedies). However, the meta-meaning conflicts with an unfortunate reality. The political organs established by the Constitution have ceased to function. Moreover, we have ample evidence that this stalemate is exactly the political result favored by legal conservatives.

We have seen this before. In 1860. In 1936. Actually, we even witnessed this happen in 1786. The stalemate is called a Constitutional crisis. Under these circumstances, the principles that support the rule of law in the United States — equality, fairness, justice, transparency — principles enshrined within the preamble to the Constitution itself, begin to crack and crumble. Legal conservatives therefore face a dilemma. Is the Constitution a means? Or is it an end? They will tell us the Constitution is an end — a Procrustean bed as it were. But legal conservatives employ the Constitution as a means. To reconstruct politics itself, a breathtakingly radical, and risky, dissimulation that wagers all in the service of a hidebound medieval vision.