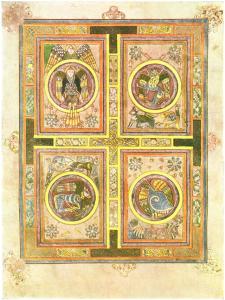

Symbols of the Four Evangelists, Book of Kells, (Wikimedia Commons)

This article will explore the state of the development of the Canon of the New Testament in the 4th century. In this context, the word “Canon” signifies “the catalogue of inspired writings known as the Old and New Testaments, identified as such by the Church.”[1] The Canon of the New Testament, defined by the Catholic Church at the Council of Trent (1545-1563), includes the 27 Books that all Christians contain in their Bibles. Many are aware that there is a variation in what books are accepted as the Old Testament Canon between Christians. Protestants accept 39, the Catholic Church recognizes 7 more (referred to as “Deuterocanonical”), while that of Orthodox Christians contain all of the 7 Deuterocanonical Books, and more (depending on the particular church.) What is less known, is that all the way into the 4th century there was some hesitation among various particular churches in accepting some of the 27 Books that all Christians now accept as the New Testament Canon.

Written in the early 4th century, Eusebius of Caesarea’s Ecclesiastical History covers the history of the Church from Jesus and the Apostles through A.D. 324, just prior to the Council of Nicaea. Since it is the first history of the Church, it earned this Bishop of Caesarea the moniker of “Father of Church History.” In Book III, chapter XXV of this work, he relays the state of the New Testament Canon ca. 325. After discussing the Books accepted by all (he gives some reservation about the Book of Revelation), he turns to those which are disputed:

“Among the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many, are extant the so-called epistle of James and that of Jude, also the second epistle of Peter, and those that are called the second and third of John, whether they belong to the evangelist or to another person of the same name.”

[2]

All of these Books, of course, are included in the 27 that all Christians now accept. He continues:

”Among the rejected writings must be reckoned also the Acts of Paul, and the so-called Shepherd, and the Apocalypse of Peter, and in addition to these the extant epistle of Barnabas, and the so-called Teachings of the Apostles; and besides, as I said, the Apocalypse of John, if it seem proper, which some, as I said, reject, but which others class with the accepted books.

And among these some have placed also the Gospel according to the Hebrews, with which those of the Hebrews that have accepted Christ are especially delighted. And all these may be reckoned among the disputed books.”

[3]

Besides listing some well-known works of the Apostolic Fathers, such as the Shepherd of Hermas, the Epistle of Barnabas, and the Didache, one can see that he includes the Book of Hebrews as well, and notes the reservation among some regarding the Book of Revelation (“Apocalypse of John”). What he notes about Revelation can be verified in St. Cyril of Jerusalem’s (d. 386) Catechetical Lectures (Lecture IV, XXXVI). The Bishop of Jerusalem writes to his catechumens:

“Then of the New Testament there are the four Gospels only, for the rest have false titles and are mischievous. The Manichæans also wrote a Gospel according to Thomas, which being tinctured with the fragrance of the evangelic title corrupts the souls of the simple sort. Receive also the Acts of the Twelve Apostles; and in addition to these the seven Catholic Epistles of James, Peter, John, and Jude; and as a seal upon them all, and the last work of the disciples, the fourteen Epistles of Paul. But let all the rest be put aside in a secondary rank. And whatever books are not read in Churches, these read not even by yourself, as you have heard me say. Thus much of these subjects.”

[4]

If one does the math, one counts 26 Books, and the Book of Revelation is omitted. Everything else besides the 26 listed, the Bishop tells his catechumens, are to “be put aside in a secondary rank”. As an Eastern Bishop, St. Cyril is reflective of the hesitancy among those in the East in accepting Revelation as canonical. This can also be seen in Canon 60 from the Council of Laodicea (A.D. inter 343/381.)[5] One notable exception is in Alexandria, where St. Athanasius (d. A.D. 373) lists it in his Epistle 39.[6] This objection to Revelation mostly died out among the Greeks by the beginning of the 5th century.[7]

In the West, a Roman Synod under Pope St. Damasus I in A.D. 382 lists the 27 Books all Christians now hold.[8] Although there was some hesitancy in accepting the Book of Hebrews in North Africa, the predominant view represented by St. Augustine of Hippo prevailed, with all 27 Books being catalogued in regional councils at Hippo and Carthage between the years A.D. 393 – 419.[9] These were later listed and approved at the reunion Council of Florence (1438), which attempted to heal the schism between the Greek and the Latin churches but was later repudiated by the former. Finally, they were all declared to be inspired Scripture at the Council of Trent, a little over a century later.

I hope you have enjoyed this post. Please consider subscribing to the e-mail list to be notified about recent posts.

[1] https://www.catholicculture.org/culture/library/dictionary/index.cfm?id=32293 (accessed 1/23/2019.)

[2] Translated by Arthur Cushman McGiffert. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. <http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/250103.htm>.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Translated by Arthur Cushman McGiffert. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. <http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/250103.htm>.

[5] William A. Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers (Vol. 1), (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1970), 318-319.

[6] Translated by R. Payne-Smith. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 4. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. <http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2806039.htm>.

[7] Reid, George. “Canon of the New Testament.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 24 Jan. 2019 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03274a.htm>.

[8]William A. Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers (Vol. 1), (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1970), 406. Jurgens includes a historiographical discussion on the “Decree of Damasus”, the second part of which contains the information on the New Testament Canon (pg. 404.) While acknowledging that a minority attribute it to the “Gelasian Decree”, he notes that: “It is now commonly held that the part of the Gelasian Decree dealing with the accepted canon of Scripture is an authentic work of the Council of Rome of 382 A.D., and that Gelasius edited it again at the end of the fifth century, adding to it the catalog of rejected books, the apocrypha [this does not refer to the 7 Books of the OT Catholic Bibles have that Protestants do not, which Catholics refer to as “Deuterocanonical”]. It is now almost universally accepted that these parts one and two of the Decree of Damasus are authentic parts of the Acts of the Council of Rome of 382 A.D.” Pg. 404.

[9] Reid, George. “Canon of the New Testament.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 24 Jan. 2019 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03274a.htm>.