(Wikimedia Commons).

In wrapping up his First Epistle, the Apostle Peter makes a cryptic reference to his location, stating that, “The church that is in Babylon, elected together with you, saluteth you: and so doth my son Mark.”[1] The “Mark” referenced here is the author of one of the four Gospels, and whom according to tradition, was a companion of the Apostle.[2] It is the same Mark that tradition claims was sent to Alexandria by Peter, becoming the first Bishop of that city.[3] But what about the reference to “Babylon”?

According the first historian of the Church, Eusebius of Caesarea (d. ca. A.D. 340), Peter was actually writing from Rome.[4] Eusebius bases his statement on the authority of Clement of Alexandria (d. ca. A.D. 215), and Papias, Bishop of Hierapolis (d. ca. A.D. 130).[5] This was also the view of Jerome (d. A.D. 420), who stated in the eighth chapter of his De Viris Illustribus that: ‘St. Peter also mentions this Mark in his First Epistle, while referring figuratively to Rome under the title of Babylon’.[6] As The Catholic Encyclopedia notes, “[this view] may be said to have been questioned for the first time by Erasmus [d. 1536], whom a number of Protestant writers then followed, that they might the more readily deny the Roman connection of St. Peter”.[7]

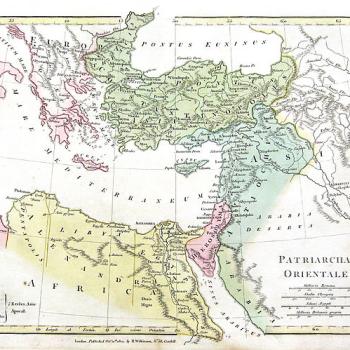

In his 2004 work, The Early Coptic Papacy: The Egyptian Church and its Leadership in Late Antiquity, Stephen J. Davis provides a more recent historiography with respect to 1 Peter 5:13. In it, he enumerates three possibilities for the reference to “Babylon” in that text: 1). Babylon in Mesopotamia; 2). the name of an ancient Roman military fort in Egypt; and 3). Rome, the Eternal City.[8] The first he dismisses because of a lack of any Christian tradition.[9] The second he rejects due to the absence of written evidence demonstrating that Peter ever traveled to that fort, or that it even existed at that time.[10] Moreover, he notes that there is archaeological evidence suggesting that it was not built until the third century.[11] With respect to the third option, he remarks that:

“Most now opt to interpret ‘Babylon’ metaphorically as a reference to the city of Rome. By the end of the first century, ancient Jewish and Christian apocalyptic writers both began using ‘Babylon’ as a symbolic name for the imperial city. In the early church, this symbolic usage is typified by the writer of Revelation (14:8; 16:19; 17:5; 18:2, 10, 21), who envisions the fall of Babylon (Rome) as the result of God’s judgment. In ancient Jewish and Christian interpretation, Babylon was often remembered as a place of exile; thus, in the context of 1 Peter, the writer may be evoking Babylon at the conclusion of his letter to convey to his readers his sense of solidarity with them as ‘exiles of the Dispersion’ (cf. his opening greeting in 1:1).”[12]

Thus, contemporary scholarship favors the view of the aforementioned ancient authors, namely, that “Babylon” is speaking figuratively of Rome.[13] What is more, the question does not appear to necessarily be split along Catholic and Protestant confessional lines as may have once been the case.[14] For example, the entry for 1 Peter 5:13 in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: New Testament authored by the faculty at Dallas Theological Seminary adopts the historical view, while also noting that others argue that “Babylon” refers to the Mesopotamian city-state rather than Rome.[15] In light of the entirety of the evidence presented above, the latter view is a difficult one to maintain.

Thanks for reading! Please consider leaving a comment, subscribing, or sharing via your favorite social media platform.

[1] 1 Peter 5:13. Drbo.org. Accessed 8/7/20.

[2] Cf. Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, I. Translated by John Patrick. From Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 9. Edited by Allan Menzies. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1896.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/101601.htm . Also, Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 2:15.

[3] Cf. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 2:15-16.

[4] Ibid, ch. 15.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Cited in, MacRory, Joseph. “St. Mark.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 7 Aug. 2020 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09672c.htm .

[7] MacRory, Joseph. “St. Mark.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 7 Aug. 2020 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09672c.htm .

[8] Stephen J. Davis. The Early Coptic Papacy: The Egyptian Church and its Leadership in Late Antiquity. (New York: AUC Press, 2017), 4-5.

[9] Ibid, 5.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Cf. A. Edward Siecienski. The Papacy and the Orthodox: Sources and History of a Debate. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 44. See footnote #156.

[14] See the above discussion on Erasmus of Rotterdam. Cf. Rev. George Leo Haydock’s transcribed notes for 1 Peter 5:13 in the Catholic Family Bible and Commentary.(New York: Edward Dunigan and Brother, 1859). https://www.ecatholic2000.com/haydock/title.shtml

[15] Roger M. Raymer. 2004. 1 Peter. Bible Knowledge Series, edited by John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck. Colorado Springs: Cook Communications Ministries, 857.