Comments that the primate of the Russian Orthodox Church made earlier this week caused something of a stir on the internet. As the Associated Press reports, Patriarch Kirill gave a sermon this past Sunday wherein he assured his listeners that “If someone, driven by a sense of duty, the need to fulfill an oath, remains true to his calling and dies in the line of military duty, then he undoubtedly commits an act that is tantamount to a sacrifice”. “And therefore we believe,” he added, “that this sacrifice washes away all the sins that a person has committed.”[1] According to ABC News, Russian President Vladimir Putin gave a “fiery speech” from the Kremlin Palace on Friday wherein he took aim at the United States and the West. Among other things, Putin criticized American policies related to gender ideology as being “satanic”, arguing that “those poisonous fruit have become visible, not only to people in Russia, but also many in the West.” Thus it seems that there is a religious element to this war from the perspective of both Patriarch and President. Indeed, the Ukrainian Orthodox Priest Cyril Hovorun noted back in May, 2022 that “You cannot call it a religious war, but it has a religious dimension”.[2]

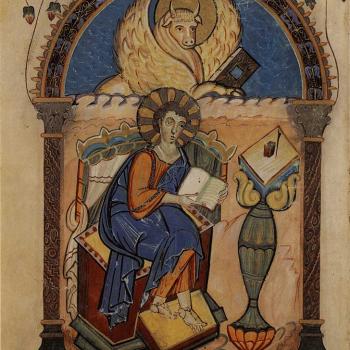

The intent of this article is not to make any moral judgments on the words of Patriarch Kirill, rather to use them as an entry point to discuss the idea that those Christians who die fighting in battle are counted as martyrs. To be clear, the Russian Patriarch did not make this connection himself. Nevertheless, the concept of the remission of sins for bearing arms, and that of the combatant as martyr were associated in crusading ideology, at least at the popular level. The latter concept took firm root in the Latin speaking West during the Middle Ages, and became rather widespread during the crusading movement[3], inaugurated by the preaching of Pope Urban II at a council in Clermont in A.D. 1096. Pope Urban of course was not speaking in a vacuum as he pulled together strands of thought already in existence in preaching what came to be known as a “crusade”.[4] But this term came to be utilized to describe a particularly Catholic (and Western) phenomenon; after all one of the key components of the crusade was the crusading indulgence, and indulgences are distinctly Catholic.[5]

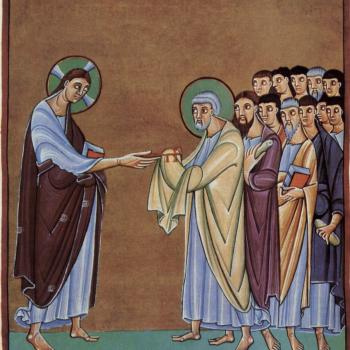

As H.E.J. Cowdrey notes, the idea that Christians who died fighting in battle were martyrs seems to have been expressed explicitly by Pope Leo IX while his armies were engaged in defending Italy from Norman invaders in 1054. He was followed by Gregory VII[6], who tried to incite western knights to come to the aid of the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I because the Seljuks were overrunning his Empire. The idea is found in the words of Bishop Bonizo of Sutri (d. 1090), when he remarked:

“As for those who had been struck down in battle when fighting for righteousness (pro justitia), God has shown by signs and miracles that they have been well pleasing to him, thus giving great confidence in fighting for righteousness to those who come after when [He] has deigned to reckon them in the number of the saints”.[7]

After the First Crusade examples can be multiplied. In his defense of the formation of the Knights Templar, St. Bernard of Clairvaux (A.D. 1090 – 1153) exclaimed in reference to these warrior-monks: “How gloriously victors return from battle! How blessedly martyrs die in battle!”[8] King James I of Aragon expressed the same idea when he was engaged in the conquest of Islamic Valencia. During the campaign, he commissioned his maternal uncle to hold the castle they had recently won at el Puig de Cebolla. When the latter expressed some concern, the king assured him that, “if God allows you to fulfil this service which we have ordered you to do, I will make you the most honoured man in my kingdom, and if you die in God’s service and ours, you shall certainly obtain paradise”.[9] No doubt James had absorbed the crusade preaching of the era. The idea that those who died under such circumstances were martyrs – provided they were in a state of grace – is clearly expressed in the preaching of James of Vitry, who wrote that, “those crusaders who prepare themselves for the service of God, truly confessed and contrite, are considered true martyrs while they are in the service of Christ….”[10]

When James’s uncle did ultimately fall in defense of el Puig, he assured the mourners that “his soul, as all good Christians must believe, will go to a good place”.[11] Though the ideology of crusades was eventually superseded by modern conceptions related to the use of force,[12] there were still bits and pieces to be found in the modern era, notably in the rhetoric of the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). But this has been to speak of the West and its crusading movement. What of the East?

Historians have hitherto pointed out that crusading is not part of the Eastern experience, and rightly so. Nevertheless, as Thomas Madden indicates, “the Christians of the eastern Roman empire…were willing enough to flirt with the idea of holy war during Emperor Heraclius’s (610-641) campaigns against the Persians. When the forces of Islam exploded onto Byzantine lands shortly thereafter, however, the idea did not resurface.”[13] After the Latins sacked Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, it made a reappearance. That city’s Patriarch suggested that the Byzantines launch a campaign to take back the capital, and he included spiritual rewards. However, as Michael Angold notes, this was not according to Byzantine tradition.[14] A similar appropriation of the crusading ethos occurred in twentieth-century Romania, while under fascist rule. In response to the Soviet occupation, the Romanian Orthodox Patriarch Nicodim remarked that, “God has shown to the leader of our country [Ion Antonescu] the path toward a sacred and redeeming alliance with the German nation and sent the united armies to the Divine Crusade against destructive Bolshevism….”[15]

In response to the Russian Patriarch’s words this week, Rev. Cyril Hovorun remarked that “What [Kirill] said is somewhat reminiscent of the statements of some religious leaders of radical Islam, who, for example, call on the faithful to sacrifice their lives, take the lives of others and promise them paradise for this.”[16] The debate on whether or not Christian conceptions of “holy war” were borrowed from the Islamic notion of jihad during the Middle Ages notwithstanding,[17] the Russian Patriarch could have just as easily drawn inspiration from somewhere else.

[1] I have yet to find the entirety of the sermon in an English translation online, but these words (and more) can be found in various anglophone news sources around the web.

[2] In Peter Smith, “Russian talking point: Blaming US for Ukraine church split”, March 23, 2022, accessed 10/1/2022. https://religionnews.com/2022/03/23/russian-talking-point-blaming-us-for-ukraine-church-split/

[3] Cf. Jonathan Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading (London: Athlone Press, 1986), 116.

[4] Cf. H.E.J. Cowdrey, “Christianity and the morality of warfare during the first century of

crusading.” In The Experience of Crusading (Vol. 1), ed. Marcus Bull and

Norman Housley, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 183-184; Thomas Madden, The Concise History of the Crusades, 9. The idea that crusaders were martyrs was not necessarily one of those ideas.

[5] Cf. Jonathan Riley-Smith, What Were the Crusades, (San Francisco, Ignatius Press), 4-5. There he lists four key ingredients: “To contemporaries…a crusade was an expedition authorized by the pope on Christ’s behalf, the leading participants in which took vows and consequently wore crosses and enjoyed privileges of protection at home and the indulgence, which, when the campaign was not destined for the East, was equated with that granted to crusaders to the Holy Land.”

[6] Cowdrey, “Christianity”, 178.

[7] In Cowdrey, “Christianity”, 178-179.

[8] Bernard of Clairvaux, In Praise of the New Knighthood”, trans. M. Conrad

Greenia. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2008, chapter 1, 34.

[9] James I of Aragon, The Book of Deeds of James I of Aragon: A Translation of the

Medieval Catalan Llibre dels Fets, trans. by Damian J. Smith and Helena

Buffery, (New York: Routledge, 2016), chapter 207, 188. Hereafter, signified by LF

[10] Sermon 2:17, in Christoph Maier, Crusade Propaganda and Ideology: Model Sermons for the

Preaching of the Cross (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 113.

[11] LF, chapter 232, 203.

[12] Cf. Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 297-298. There he traces the decline of crusading ideology from the sixteenth century onward.

[13] Madden, Concise History, 3.

[14] This anecdote comes from Michael Angold, The Fourth Crusade: Event and Context (Harlow: Pearson Education Limited,

2003), 200.

[15] Michael Burleigh, Sacred Causes: The Clash of Religion and Politics, From the Great War to the War on Terror, (New York: Harper Collins, 2007), 272. My emphasis.

[16] In Opinions, “’In fact, it’s religious terrorism’: Russian Orthodox Church, through Patriarch Cyril, confuses martyrdom with murdering Ukrainians”, September 30, 2022, accessed 10/1/2022. https://df.news/en/2022/09/30/in-fact-it-s-religious-terrorism-russian-orthodox-church-through-patriarch-cyril-confuses-martyrdom-with-murdering-ukrainians/

[17] Cf. Madden, Concise History, 3-4. “It would be too strong to say that it was the idea of jihad that led to Christianity’s own concept of holy war [he goes on to discuss the Emperor Heraclius d. A.D. 641]…. ”