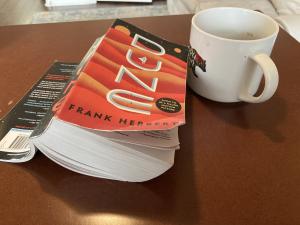

Is theology small-minded? Does it, I mean, depend on a limited perspective? That’s an assumption that shows up often in science fiction. Basically: the more we know, the less we believe. I’ve recently finished reading Frank Herbert’s Dune—yes, I’m one of those who finally read the book because the movie was coming out. I haven’t seen it yet, and won’t spoil anything from the story. But it’s got me thinking about theology and perspective again. What does a grand cosmic plot-scale mean for the religion of Dune?

Is theology small-minded? Does it, I mean, depend on a limited perspective? That’s an assumption that shows up often in science fiction. Basically: the more we know, the less we believe. I’ve recently finished reading Frank Herbert’s Dune—yes, I’m one of those who finally read the book because the movie was coming out. I haven’t seen it yet, and won’t spoil anything from the story. But it’s got me thinking about theology and perspective again. What does a grand cosmic plot-scale mean for the religion of Dune?

Herbert, an author of almost overwhelming imagination, invites us into a universe in which all local rituals and doctrines have come literally ungrounded. Space travel has changed commerce, language, and law. It has also changed what it means to believe and practice religion. The religious backstory is something like this.

The Religion of Dune

Humans begin to travel through space and discover new worlds. While this certainly decenters the human experience in the cosmos, it also brings them a new sense of community. So, for instance, when artificial intelligence threatens to destroy humanity, they go to war. This struggle, “The Butlerian Jihad,” puts in place a basic and apparently compelling regulative moral principle: humans are irreplaceable. Sacred, one might say. Some of the best mid-century science fiction wrestled with that question. Asimov, Dick. James Cameron much later.

Alongside the struggle for human irreplaceability is a struggle for religious reconciliation. An interfaith committee works for years, amidst new rebellions, to create a pan-human religion. As the name of the machine-war suggests, Islam’s vocabulary becomes more or less universally accepted. Herbert does not—in the little I’ve read anyway—explain how or why this happens. The vocabulary is Persian, the Fremen of Arrakis (the dune planet of the title) retain some Muslim customs. It seems that the committee’s work is to expand the Koran and the worship of Allah into interfaith propositions and ethics. They even produce a pan-religious text, the remarkably named Orange Catholic Bible.

Strangely Familiar Faiths

Herbert was quite intelligent, in fact, about the variety of rites and the complex history of Islam, especially its struggles with colonial powers. I see this as key to Paul’s internal dialogue (and not only Paul’s), which forms an important element of the slow-developing storyline. Jihad, which most recognize as a term for holy war, is also a word for self-discipline, or internal struggle. Some, in fact, consider this the primary jihad. It seems that this internal dialogue is missing from the film, and I’d say in that case a major element of the religion of Dune is also missing.

The opening scenes of the book make it clear that the “irreplaceable humanity” principle will be a major motivating engine of the plot. Paul, the hero/anti-hero, undergoes a painful test to prove that he is human. When he hears of the wild Fremen of Dune, he asks his father nervously if they’ve morphed into something no long human. Later, alongside them, he learns how retaining religion has become part of their resistance. “They denied us the Hajj!” they call out to one another in a ritual, referring to the Muslim pilgrimage.

The religion of Dune is strange, even as it familiar. Gurney Halleck, a wizened old warrior minstrel, is constantly quoting the O.C.B. Some passages could be Psalms, others are clearly revisions of Genesis. The Bene Gesserit, a Jedi-like (sorry purists, In couldn’t resist) order of women, quote Saint Augustine. We’re in a religious world we recognize. But just barely.

Religion and the Extremes of Difference

In the end, that strange familiarity is my favorite element of the religion of Dune. So much since fiction imagines that faith dissolves as horizons expand. Alien life marks childhood’s end, as Arthur C. Clarke put it. My friend Alan Gregory wrote about this, and in fact considered “Childhood’s End” as the title for his book, before worrying that it might get confused with Clarke’s novel. “The peculiar suggestiveness of science fiction for Christian faith lies not in its critique of divinity, which is largely misplaced . . . but in its imaginations of radical otherness. . .” The genre, he means, can show us places and beings right at the far reaches of our imagination. And then rather than call for a rejection of God, it can invite us to wonder what it might mean to go on believing in God in light of all that otherness.

Herbert doesn’t think space travel marks the end of faith. He thinks that expansion of lived horizons invite us to reach, as Gregory put it, “toward the extremes of difference.” I am not particularly compelled by the pan-religious committee’s work to unify all human faith. But then again, I don’t think Herbert was either. Religious unification is an imagined human project that goes badly, and to that extent it sounds not all that unlikely.

If you read the books, or watch the films, or both, I hope that you’ll enjoy a really good story. If you manage, in addition, to wrestle a bit with the religious elements, I think you may find a compelling idea at work in Herbert’s universe. Encounters with difference—wild, unimagined, categorical difference—change us. They change our customs, our language, and our beliefs. But rather than spelling the end of faith, these encounters can invite faith’s expansion and complexification.

Thanks to Will Sherman and Dan McClain for helping me see new things about the novel. And to my son Lev for challenging me to read it. I imagine he’ll roll his eyes when he reads what I’ve done with it here.