In this first week of Advent, I’m contemplating Mary the Godbearer. All who celebrate Christmas in one way or another, from priest to grandmother to toddler, are contemplating her. We’re waiting for the birth. Packing nine months gestation into four Sundays. For the next 24 days, we’re all pregnant with Emmanuel. We’re all Mary, this month.

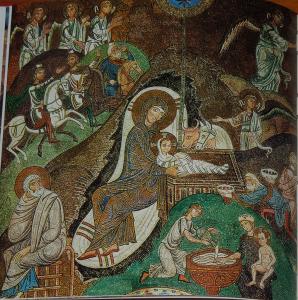

On my wall at home I’ve hung an Orthodox icon of the Nativity. It’s a wild piece of art, as icons go. All around the border are dramatic scenes of the birth narrative: shepherds wondering at angel song, Magi en route, Joseph contemplating divorce, the swaddled child. And in the center Mary reclines peacefully, outlined in bright red in my version. The icon wants me to notice the child. But first it wants me to find myself in Mary.

The Thrill of Mary the Godbearer

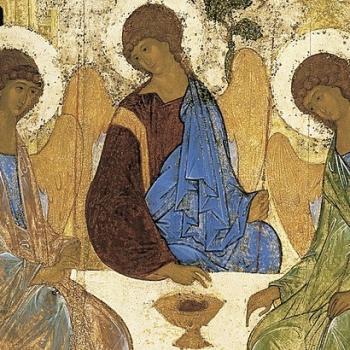

A Marian piety is a good thing to have, whether you’re Roman Catholic, Protestant, or Eastern Orthodox. Fr. Sergei Bulgakov of the Russian Orthodox Church writes that Mary is a focal point of the Christian faith, as the figure of a human who is “forever conceiving God, holding him in her womb, giving birth to him.”

That’s what I want to be. I want to conceive, gestate, and birth God into the world. I want to be like Mary.

That notion, that a human can be a Godbearer, was both thrilling and offensive in the first centuries of Christianity. It generated a view of Jesus, in fact, that was eventually declared heretical. That view says that Jesus had a human being and a divine being, but only the human part was born from Mary. She is human-bearer, not Godbearer. It could be that the idea of God passing through not just humanity, but the body of the woman, made this doubly offensive. A later version said that we can call Mary Christotokos, Christbearer, but not Theotokos, Godbearer.

The argument against the first version, that Mary was only a humanbearer, was that if Mary only conceived and bore the human, then God is not actually with us in Jesus. Jesus, in that case, would have been sometimes human, sometimes divine, but never the union of both in a a single Person.

The argument against the second version, that Mary was Christbearer but not Godbearer, was that the second version was avoiding the issue and so not really worth arguing with.

It was an offensive idea. But it was also a thrilling idea, one I’ve written about before. That two ways of being that seem mutually resistant by definition, divine and human, are in fact not. The thrill is how God does not push aside a young powerless girl from Nazareth, but instead waits on her response. Divine saving work comes mediated through human agency. In Mary, a human conceives, bears, and delivers God into the world.

Thrilling: the possibility that all humans can find our calling in Mary the Godbearer. That we can bring into the world the One God of Israel, shaped by our own bodies.

Bodies Mediating Grace

Luke’s Gospel shows the thrill of this human mediation. Mary introduces grace through her body right away, as her story intersects with her another’s. Mary and the priest Zechariah have nearly identical stories, but the order is essential:

- Gabriel visits Zechariah. When the angel tells him that he and Elizabeth will give birth, he asks, “How will I know?” After all, “my wife is getting on in years.”

- Gabriel visits Mary. When the angel tell her that she will give birth, she asks, “How can this be, since I am a virgin?”

But the angel renders Zechariah mute for his response, whereas Mary gets a second chance to say “Here I am.” What is the difference?

It is not, I think, in their doubt-filled initial reply. While I love the beauty of Catholic venerations of the Blessed Virgin—pilgrimages, iconography, the Ave Maria—I find the dogma of Mary’s sinlessness to be theologically and historically questionable. I can write about that another time if you like.

It’s not the difference between Mary and Zechariah, but what happens next, that is the key.

- Mary visits Elizabeth

- Elizabeth’s child leaps in the womb

- Zechariah’s lips are opened

Luke is showing the centrality of Mary’s body, and the body of the one she carries. The child conceived in Elizabeth will “make ready a people prepared for the Lord.” In the visitation scene, though, the one who “makes people ready” is now Mary’s child. Pre-natal John leaps in the womb at pre-natal Jesus’ presence. Then Elizabeth goes back home, insists on the name the angel told to Zechariah, and suddenly her husband’s throat is healed. Body’s have mediated grace: Mary’s son has made a way.

Becoming Godbearers

Luke’s carefully ordered story reveals that Mary’s child is the homecoming of Israel’s faith, the presence of God that brings healing and hope and song for priest and virgin alike. Mary can sing her Magnificat because salvation is growing inside her. Zechariah can sing his praises again because salvation came near him when John jumped and Elizabeth brought the saving jump home.

And all that healing presence comes through a human body. That’s what I’m contemplating this Advent season. A human body that shapes Isreal’s God within it. A presence that can call up a saving jump in others it encounters. I’m contemplating Mary, as the Godbearer that I’d like to become.