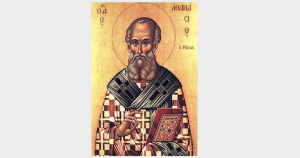

In the early 4th century, after imperial edicts ended official Roman persecution of Christians at last, theologians noticed something important. After 300 years of praying to and reflecting on the name of Jesus, the word “God” was changing. Athanasius, sometimes bishop and sometimes exile of Alexandria, made it his life’s work to pay attention to this change. In particular, he paid attention to what happened to the story of salvation, now that the story of God was shifting.

Is God Still One?

This shift came about as generations contemplated the story of the Incarnation. John 1 says that “with” God there is a Word who also “was” God. God created all things through Word. This Word became flesh and dwelt among us, apparently without ceasing to be God. For a faith committed to monotheism, this feels like a stretch. How to solve the pressure that this “with” and “was” puts on the doctrine of God? Is God less one than we’d thought? Or is Jesus, the incarnate Word, less God than we thought?

Arius, a priest of the same city a generation or so older than Athanasius, thought it must be the latter. God’s unity was of paramount importance for him, so the Son of God must be somehow “after” the Father, just as human children come after their parents. The controversy with Arius that would make Athanasius famous was about the identity of Christ. But I think it’s more helpful to see it as first of all a controversy about the identity of God. The question: how much room in God is there for difference? Arius’s answer was clear and sensible: none. God is one, so any distinct way of being must be outside that unity.

Athanasius saw that this theology would fail to support Christian prayers. The gospels teach that Jesus is a gift of the Father, sent to make us children like he is. They teach that the Spirit is a second gift, forming Jesus’ child-like life within and among us. Ancient liturgies addressed prayers to the Father, but also to these Gifts—the Son or Word and Spirit. Were those prayers idolatry? Yes, if there is no room in God for the differences they name. If, that is, prayers addressed to Jesus are praying to a creature.

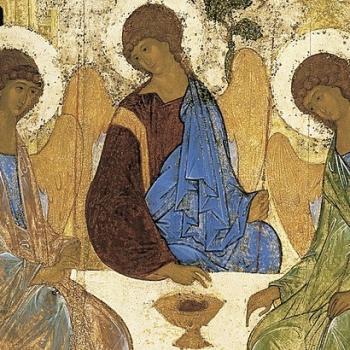

Intimacy within God

This is why Athanasius leans so heavily on the “with” and “was” of John’s first verses. There is a deep intimacy between God and Word. It’s an intimacy that doesn’t collapse the distinction, because the distinction is one of relation. God is not composed of a literal Father and Son, but parent-child language helps us see how a relationship can maintain distinction of characters even while showing a deep intimacy.

He wasn’t, though, just concerned to protect Christian prayers from charges of idolatry. He deeply believed in what those prayers hoped for. Namely, salvation as union with our Creator. This union is what we were created for, he says, and sin turned us toward a new story. In that new story, we saw ourselves as made for uncreated nothingness. Death beyond hope. The Word who was with and was God from the beginning undoes that new story through his death and resurrection. He then calls us back, through the movement of the Spirit in us, to the original story. We are new creations: re-made for union with God.

That original and final story only holds, though, if the Characters who are sent to save us are themselves in union with God. A creature, even a sublime one, can’t unite us to God. Only God can do that. So the Logos is, Athanasius says–and here he’s echoing and defending the original Creed of Nicaea–“of the same substance as the Father.” The story of the Incarnation is this: “God was humanized that we might be deified.” He’ll eventually press this case for the Spirit too, though that language takes another generation or two to get sorted.

The Analogy of Creation in Athanasius

So Athanasius says that within the unity of God there is room for difference. Maintaining that paradoxical language is as difficult as it sounds. Let’s look at one of the ways he makes this work.

Arius’s point was that if God is a Father, he is so in relation to creation. He is the Father of the world, and the Father of the Son who is the firstborn of all creation.

Athanasius responds by finding an analogy in the language. Creating is a father-like thing to do, but it’s not what makes one a parent. Creating, he says, is a temporal analogy for begetting. He’s thinking of John 3:16 here. God has only one begotten child, and in relation to that one, we are all like children. We are created in the image of the begotten one.

There is even a Greek pun that Athanasius uses to say this. “Created” is genetos. “Begotten” is gennetos, with two n’s. The Eternal Son is gennetos and agenetos, begotten but not created. Arius had said that God is entirely agenetos and agennetos, uncreated and unbegotten; he makes no distinction. Athanasius says that the Father only is both, but with the begetting of the Son there is now room for distinction in the unity of God. One who is of the same being as the Father can be different from the Father: Uncreated and Begotten.

The Intimacy We Were Made For

This is more than just clever word play. If we can describe the being of God in a way that sees a kind of generation or birthing within God, then we understand ourselves a little better. We are made in the image not just of a divine being, but of a divine birthing. Creation is not God’s eternal begotten Son, but it is like that. And if that eternal begetting means there is a deep intimacy between Father and Son, we can hope that we were created for something like that kind of intimacy.

This is the language that Athanasius fought for. An account of difference-within-unity in God that could support the Christian hope for theosis, a union with God that doesn’t end our distinctiveness as God’s creatures.