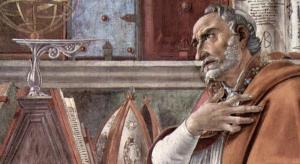

“But I am struggling to return from this far country by the road he has made in the humanity of the divinity of his only Son.” -Saint Augustine

Saint Augustine’s theology pulses with motion. From the relay of signals among created things, to the loving gift-exchange whom he calls God, everything moves. When I read his sermons and treatises, I find myself in a world flowing with God’s love. And I find myself challenged to let this love move me and move within me. This makes him a key mentor for my diagonal journey toward the heart of God.

Restless Hearts

Augustine’s memoir of the first half of his life begins and ends in movement. “Our hearts are restless,” is his famous beginning. The book ends with God opening a door to us, like a parent welcoming us home. Along the way, he moves from city to city, and from idea to idea. He tries out various philosophies along with a career in rhetoric, but finds himself urged on by a desire to stay in motion. The Platonists: I could see their beautiful city, but not how to get there. The Manichees: they helped me solve an intellectual puzzle, but left me with nowhere to go. “I could make no progress in it” becomes a kind of refrain as he describes his restless journey.

As one reads Augustine’s Confessions, it quickly becomes obvious that he has given us not only a life story, but also a parable. He interprets his life through the story of the Prodigal Son, as the first half of the quote atop today’s column shows. Read the rest of the quote: the parable also becomes the key to his understanding of the incarnation, as well as, eventually of God.

In and Out of Sin

Cursory readings of The Confessions focus on his obsession with sin and guilt. Many have gone so far as to blame him for bringing this obsession to the center of the western church. That’s not what I hear in his prayerful pages. I have been moved by desire all my life, I hear him saying. Only in retrospect am I able to see why. The very desire which nearly ruined me was your way of inviting me to walk toward you. Taking cues from the Prodigal, he calls “sin” any movement that takes him away from home and father. Holiness is simply the return home.

Peter Brown, in one of the great biographies of any Christian figure, notices that this desire to keep moving is what drives Augustine’s responses to other controversies later in his life. The Pelagians, for instance, were a monastic sect that saw grace as God’s response to our freely willed efforts toward God. Augustine’s critique: even our free will is God’s gift. We move because God invites, not because we decided to move. His own biography had taught him that any movement that comes from himself, without the aid of God, is not really movement at all. It’s a way of standing still.

God of Motion

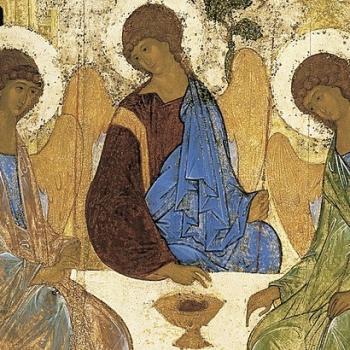

A God who can move within us is a God who is movement itself. The Holy Spirit, he says, is a Gift of love that circulates in God. That’s why he says that any true love a person encounters simply is God. “In loving love, he loves God.” God is the truth of that love, the movement of desire and celebration that does not even begin in time, but begins time. God is, from all eternity, that loving movement.

God moves without spatial migration, of course. So he says God’s eternal movement is something like a memory that a person desires to understand. My will “moves” out from this memory to the object it holds, and then returns to the memory with joy in all that it holds. God, he says, is something like that. The eternal cycling exchange of memory, understanding, and will.

The Way from Eternity to Time (and Back)

This motion within God becomes Augustine’s lens when he contemplates and preaches on the incarnation. God who is a motion of love also moves toward us. This is the piece that he found missing in his beloved Platonists. They could describe, often very beautifully, the home he was longing for. But they could not provide the path. He could make no progress there.

So the divine Understanding itself became a path. The irony of the gospel is that all our attempts to improve our state, whether through acquisition or through thinking higher thoughts, keep us off this path. “They do now know him as the Way whereby they can climb down from their lofty selves to him, and thus by him ascend to him.” In Christ we discover the humble character of our Creator. God’s love for the small, the poor, the forgotten, and the broken. And that Way toward us is also a way for us.

The Word of God comes humbly, and invites us not to separate ourselves out as an authentic church, as the Donatists did. Nor to celebrate our own self-initiated motion, as the Pelagians did. Instead, God provides a path into what is least worthy of celebration in us. Christ is my invitation to surrender “the itch to justify myself,” and simply walk in Christ’s humble humanity toward his justifying divinity.

Moving at Home

As we do, we may just find the love that is God moving within us. Augustine thinks we will, and he calls this movement “salvation.” We get to share in our own salvation, in our own getting right with God, Augustine says. Not as motivators, but as participants.

Here is where we find the promised rest, which is not at all like standing still. It is more like moving about our own familiar spaces. Dancing with our family in the kitchen, opening a door for friends. Or, as in the Prodigal story, bustling about to cook a meal for our household. In other words, all the ways we move when we find ourselves no longer restless, but finally at home.