The Humiliation of the Son of God

“What kind of descent into humiliation is that?”

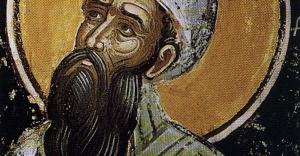

This question, from Cyril of Alexandria’s commentary on the Gospel of John, made me pause. It made me scrunch my eyebrows and scribble something illegible (sorry, Mrs. Wodock, I never learned penmanship) in the margin. The fifth century Church Father is wrestling here with the baptism scene in John. Specifically, the Spirit’s “descending like a dove” onto Jesus.

He’s also got Philippians 2 open in front of him. Intertextual readings like that are the rule rather than the exception in ancient commentaries. Paul says that when Jesus was “in the form of God,” he humbled himself and took on the nature of a slave. (That’s a harsh noun, but it’s the one Paul chose.)

So when Cyril reads the texts together, he makes an important discovery about the identity of Jesus. His self-emptying in heaven allows for his sanctification on earth. That’s a loaded line, so let’s slow down. A little background will help us see what Cyril is up to.

Cyril’s Worst Moments

Cyril, it should be said, tended not to be a fan of humility. Not his own, at any rate. He seems to have been much more comfortable with the humiliation of others. He became Archbishop of Alexandria in early 5th century. The city, once a rich inter-religious marketplace of ideas, had descended into ugliness. Jews and Christians attacked one another no longer just with words, but with torch-bearing mobs.

Cyril, relatively young when he became Archbishop, did not remain aloft from he violence. It’s impossible to know the degree of his involvement, but it seems that he at least stood by silently as Christian mobs attacked pagan and Jewish citizens. He eventually banished Jews from the city, forever impoverishing not just Alexandria, but Jewish-Christian relations generally.

I don’t want to ignore that ugly history. At the same time, I want to extend Cyril the grace I extend others, including myself. I try, that is, not to take a person’s worst moments as their defining moments. An anti-Judaism certainly marks Cyril’s writings. In this he is not unique. An elegant solution to a Christological difficulty also marks his writings, and this is why we remember him among the Fathers and even Doctors (on the Roman Catholic calendar) of the church.

The One Person that Jesus Is

That elegant solution is what he calls the “hypostatic union.” The great theological question of his era was the matter of Christ’s unity. The church had at this point reached consensus about his divinity. They’d also reached consensus about his humanity. Both were fully present in an uncompromised way in the one walking through Galilee in the Gospel stories. But how then is he one figure and not two? Full divinity can’t mix with full humanity, can it? Wouldn’t that blow a person up?

Cyril read deeply in the earlier writings of folks like Athanasius and Gregory of Nazianzus as he entered this debate. He also meditated, with his friend Pulchera, the Emperor’s big sister, on the role of Mary in God’s plan of Incarnation. This was key. But that’s a blog for another time. A biography tells this story really well.

He eventually comes up with the language that has become the traditional way of speaking of Jesus. He had two complete natures, and both natures were united in one Person (hypostasis in Greek). The divine person we called Son or Word was by nature fully God. The incarnation is the account of this divine person uniting to itself a human nature. Jesus’ story, from birth through ascension, is what it looks like for the Son, whose life is naturally divine, to live a fully human life as well.

So when you point at Jesus, you are pointing at God. Not because Jesus is the sum of the Godhead. The eternal God is not a Galileean Jew who got sleepy in a boat or whose feet got dusty and needed washing. But a person of the Trinity humbled itself and, without ceasing to be God, also became a sleepy Jew with dirty feet.

The Humiliation and Theosis of the Son of God

Young Cyril, writing the John Commentary, has not yet entered into the debate that will lead him to speak of this hypostatic, or personal, union. But in this passage we can see him stepping toward it.

It’s possible, he is noticing, to read the baptism story as an account of a man from Galilee who is sanctified in a special way by the descent of the Spirit. That’s an old (by Cyril’s time) heresy known as adoptionism. God adopts a man to become his Messiah.

Cyril challenges this reading not by saying, “that’s heresy, stop it.” Instead, he reminds us that humility is an essential part of the story, and even an essential character of God. If, when the Spirit descends like a dove, we are seeing a man becoming God, this is not the story of a God who humbles Godself. “What kind of descent into humiliation” would that be? It would rather be a divination of one who is properly—hypostatically—human.

But God shows us what true divinity looks like when the divine Son humbles himself and take on the nature of one who does, actually, need sanctification. That’s what the descending Spirit is up to, Cyril says: sanctifying Jesus’ humanity. Jesus, who personally is holy with God’s holiness, humbles himself and becomes one whose life can be a long human journey of theosis, holiness. And if his life can be that, so can ours.

The one whose union with God is immediate and eternal becomes one whose holiness is diagonal and temporal. This, for Cyril, is what the divine descent into humiliation looks like. That’s likely what I scribbled in the margin as well. But we’ll never really know.