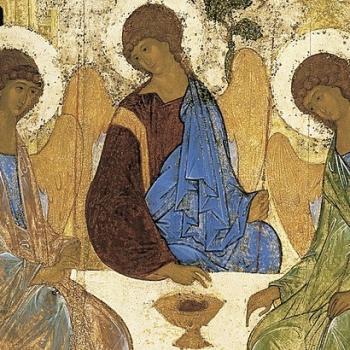

At wikicommons.org

It’s Ash Wednesday. What is that again?

Today, Christians in the Western traditions begin the liturgical season known as Lent. We actually combine two parts of the gospels in the “back story” of Lent. First, we recall and repeat the temptation of Christ in the wilderness for 40 days. Secondly, we recall his approach to Jerusalem, and the events leading up to his crucifixion.

So Catholic and Protestant Christians today will receive on their foreheads ashes from last Palm Sunday’s leaves. And we will hear priests and pastors remind us that we were made from dust, and will one day return to that state.

Lent is not an annual opportunity for self-improvement. Neither, though, is it a time to withdraw from worldly affairs into a navel-gazing spirituality. Instead, it is a Christian season of courage and honesty. Courage to discover who we humans are, actually, in the world, and honesty enough to name what we discover.

I am reposting from a year ago my discoveries and attempts at honesty, contemplating Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The war has now entered its second year. Putin is threatening to withdraw from the last major nuclear nonproliferation treaty. What sort of Lenten courage and honesty does the war-making in Ukraine invite us to?

Witnesses of Various Sorts

Tanks roll into cities. Putin threatens the NATO allies with his nuclear arsenal. Meanwhile, Ukrainians reach in desperation for their grandfather’s hunting rifles while others collect their children’s Coke bottles for Molotov cocktails.

While all this goes on, the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church is embarrassing itself. Orthodoxy, especially in Eastern Europe, is politically complex. The churches suffer from a particular heresy often called, albeit anachronistically, “Erastianism.” The word comes from the Protestant Reformation, but has come to be used for any political structure in which the church is compromised by its subservience to the state. It is painful to hear Patriarch Kirill say whatever Mr. Putin wants him to say.

Still, the courageous act of 176 clerics of the Russian Church, calling for the war’s end, looks to me like a light in the darkness. So do the protests on the streets of Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

On this Ash Wednesday, I find myself reflecting on the world’s surprise at the aggression of a major player in the geopolitical theater. Why does this surprise us? Do we imagine that only “failed states” in Africa or the Middle East engage in such behavior? Or did we assume that the civilized world had, at last, moved past such unenlightened behavior?

Whatever the cause of our surprise, we ought to know by now that history is not progress. The philosophers, theologians, and economists of the 19th century preached progressive enlightenment. Until, that is, the trenches of the First World War brought that optimism up short. The madness of the 30s and 40s showed us what terrors science could add to modern war-making.

The Meaning of History

History, for Christian theology, is not progress. That’s not to say it isn’t meaningful. Rather, technology and statecraft and banking aren’t the namers of that meaning. God is the judge of the meaningful. What’s more, I believe that God’s judgment filters into the world through holy acts of humans in the midst of history.

Said differently—and with apologies for overworking the theme—the meaning of history is not linear, but diagonal. God’s presence lifts up horizontal meaning-making and makes it something that, on its own, it is not.

Acts of aggression and power—like a missile attack on a neighborhood—look deeply meaningful to us. That’s the way the masters of war intend them to look. But to God, and I hope to us also at the eschaton, such acts are utterly meaningless. They are forgotten, the way we forget a really bad poem or a story with no plot.

The faithful witness of the clergy, of those protestors, and of the desperate Ukrainian resistance, however? All that looks futile. Meaningless. But I think these acts are deeply significant, lasting manifestations of God’s unchanging judgment.

Holiness and Nothingness

I don’t say this simply because I agree with their politics on this particular question. Instead, I say it because when I read or watch video of those actions, I see courage, compassion, honesty, and loyalty. That is to say, I see the holiness of God, incarnate in human community. I think God is watching this moment in history, and celebrating the “futile” meaning-making of Ukrainian grandmothers. “Be holy as I am holy,” God says to Israel. And here, in late winter Kiev, is what God meant.

What of the cowardice, lies, and violence of the Russian state and church? I suspect God doesn’t even see it. I don’t mean God looks away. I mean it is so twisted as to be nonsense to God. Nonsense that amounts to nothing, especially when the faithful witness all around is singing such a powerful song of holiness.

This, at any rate, is how the ancient Orthodox theologians like Athanasius saw history. Wickedness tugs at us like the pull of pre-created nothingness on creation. It fills us with the nonsensical desire to unmake ourselves as holy images of the holy God. Violent, perverse, devastating; and ultimately meaningless. I suspect that one day God will stand in judgment, with the faithful clerics and armed grandmothers all around, and call such war-making the nothing that it is. Or, said in reverse: makers of this war will look to the holiness of these witnesses and confess that they do not understand what it means.

In the meantime, an important theological question remains, for Mr. Putin and his Patriarch. And in fact, this Lent in particular, for us all. Will any part of me show up as recognizably holy—as meaningful— to God? Or will I stand in judgment before a God who looks at me and sees… nothing? Will God see only precreated nothingness or, as we say in the West on Ash Wednesday, only the dust to which we all return?