“I have lived under the impression that a man’s purpose is known only to God.”

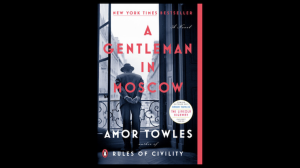

My wife, on a recommendation from a student of hers, recently bought me a novel. A Gentleman in Moscow, by Amor Towles. She knew it was a safe bet, as I’ll read nearly anything that has to do with Russia.

The story has no overt theological pronouncements to make. But that’s never stopped me from turning loose my own theological curiosities. Today I’d like to reflect on the very theological question of life’s purpose, through the lens of this novel. No spoilers—I promise.

The Business of a Gentleman

The story opens in the years just after the Bolshevik revolution. Count Alexander Rostov has returned to his native Russia from Paris, only to be dragged before a tribunal. He is convicted of harboring counter-revolutionary sentiments, and given a life sentence of house arrest in the Hotel Metropol. The hotel is an upscale establishment within a few steps of the Bolshoi Theater. Not a bad place to serve a life sentence, all things considered.

And that’s very nearly all that happens. He wakes up the next morning in his newly assigned tiny attic apartment in the hotel, and has to decided how to fill his hours. It’s not as if he has a lot of practice. “It is not the business of gentlemen to have occupations,” he informs the tribunal. He’s got 40 years to fill, and the reader has 400 pages, and we’ve all got to manage the boredom somehow!

In fact, the novel is anything but boring. It’s the small things that he–and we–will watch fill themselves with significance.

Care for language is the primary habit of life on which he will rely. In particular, language as an extension of courtly hospitality, extended to friends and strangers.

Superfluities of Language

The Bolsheviks drive him crazy in this regard. He marvels at the incapacity of the new hotel barber to make simple conversation. Here is a man so focused on “mute efficiency” that “one suspected he was part machine.” When Rostov sits for his weekly visit, the barber simply says “Trim?” —”wasting no time with subjects, verbs, or the other superfluities of language.”

The Count’s annoyance is comical, but also cuts deep. What has shifted, socially and culturally, so that we imagine language as a tool for getting jobs done, rather than a way of reaching beyond ourselves into relationship with one another? One of the sad realities of the 20th century is surely the way socialists and capitalists imitated one another in this regard.

Early on in the story one of the Kremlin’s men strips all the wine labels in the hotel cellar, since a simple choice of red and white is far more proletarian. At this offense, Rostov begins to plot suicide. Not in a fit of passion—fits of passion are also unbecoming of the aristocrats. But rather because he is convinced that there is no more purpose for him in this world he has come to inhabit.

Again, it’s tragic and comical, but it’s also more. Maybe overwrought descriptions of wine, of food pairings, or the value of a sensitive pallet all have a key place in our feasting that we too easily dismiss. They invite us to communicate about and pay attention to what we eat and drink together. Without such attentiveness, we are simply responding to a biological impulse. Maybe even wine snobbery has a deeper purpose.

Discovering Purpose

That word purpose makes its appearance at two pivotal moments in the story. The first is in the opening transcript of his trial, and contains one of the only theological references in the book. An interlocutor suggests that Rostov is “a man so obviously without purpose.” Rostov’s reply is the last thing he says in his own defense, before he is given his sentencing.

“I have lived under the impression that a man’s purpose is known only to God.”

There’s an agnosticism in that line that, we begin to see, fills the story with possibility. What if only God knows our purpose, but we get to make our own little discoveries along the way? How might we come to know what only God fully knows?

It is Rostov’s gift for language and relationships that will allow him to recover his sense of purpose. His attention to detail will lead to the unlikeliest of friendships. He will learn to sew, and taste faraway apple orchards in local honey. The precocious adventuring of a little girl will lead to him becoming, as he reflects, “the luckiest man in all of Russia.”

Late in the book, Rostov returns to the key question again. If a person pays attention, he suggests, they may find little surprises that lead to a sense of a deep transcendent signaling. “As if life itself has summoned them once again to help fulfill its purpose.” Most often these come when we’re not expecting it. And if we are not paying attention, we may just miss the summons.

Esther’s Purpose

All of this makes me think of that remarkable moment in the book of Esther, when her uncle asks her to pay attention. “Who knows but that you have come into the world for such a time as this?”

Esther is in fact less overtly theological than Towles’s book, as “God” is not even mentioned in the former. But lurking in the background of Mordecai’s passive verb is a hidden agent. Pay attention, he tells her. This random connection of events may be life summoning you to help fulfill its purpose. Mordecai lives “under the impression that a man’s purpose is known only to God.”

I don’t believe God has a plan for our lives, at least in the sense that you and I make plans. I think instead God has filled the world with purpose. God creates a world free to makes its own plans, or even to go how it goes, as King Lear puts it. God never cancels that freedom out. Nothing—whether we’re talking sickness or marriage or war or peace—ever goes according to God’s plan. That’s because God doesn’t have one.

But I do think God has filled the world with purpose. This purpose is perfectly good and holy. It’s loving and gentle and aligns with our deepest, truest desires. And I think God invites us—summons us, even—to share in this purpose.

Who Knows?

Attention to detail may just be the key to this sharing. Those moments when I manage to get distracted beyond my own drive for efficiency and notice what’s in front of me. The taste of the wine, the intense stare of a little girl. Or a stranger in need of a few well-created sentences that might let her feel acknowledged.

In the end, who knows? Perhaps we will come to suspect that one of those moments is the whole purpose for which we have been summoned into the world.