This is part of a series of reflections on opera, religion, and culture by guest writer Gregory Moomjy

Being an opera lover from such a young age, my understanding of my favorite operas deepened as I grew older. For instance, when I first saw Verdi’s La Traviata (1853) when I was eight years old, I had no concept of the importance of family honor in 18th century Europe. (At the time I was more interested in spotting the famous Drinking Song.) The fact that it is about a prostitute with tuberculosis, whose relationship with a young man from a middle-class family jeopardizes his family honor, was totally lost on me.

The same can be said for my first encounter with Verdi’s Don Carlo (1867). I was in my early teenage years when my uncle gave me a DVD of the opera for Christmas, and it quickly became my favorite. Based on the play by Fredrich Schiller—whom literary scholars recognize as ‘the German Shakespeare’—it tells the story of star-crossed lovers in the royal court of Spain in the early days of the Inquisition.

As a 13-year-old, my attention was diverted by the love story between Don Carlo (the Spanish prince) and Élisabeth de Valois (the French princess destined to be his wife, until his father—King Phillip II—marries her instead). As operatic as this plot sounds, I missed the entire backstory: where King Phillip II struggles with the Grand Inquisitor for control over the Spanish government. Throw in political troubles with the Spanish Netherlands (yes, that was a real thing), and you have the whole picture.

In Don Carlo, Verdi provides the audience with an in-depth examination of a theocracy. Verdi had a lifelong disdain for the clergy, and in his operas—whether it is Don Carlo, La Forza del Destino (1862, revised 1869), or Aida (1871)—the clergy do not survive unscathed. Nor is Don Carlo Verdi’s only look at a theocratic government. Aida, Verdi’s next opera after Don Carlo, takes place in ancient Egypt—a land ruled by priests where the Pharaoh is most definitely a figurehead. Unlike Aida, however, Don Carlo gives audience members an inside look at a theocracy, depicting battles for control of the state that occurred behind closed doors. In doing so, Verdi demonstrates the thin line between theocrats and fundamentalists.

The opera is pervaded by an incredibly Orwellian atmosphere. This is due in large part to The Grand Inquisitor: the chief of the Spanish Inquisition, who has a small but crucial role to play in the opera. Through him we see how religious fundamentalists can exploit theocratic governments for personal gain.

When Verdi was approached to write a piece for the Opéra in Paris, Schiller’s play “Don Carlos” was the ideal subject. The driving philosophy behind French Grand Opera was to examine modern day politics through the lens of previous periods of political upheaval. A relationship, whether real or fictitious, across the political divide would invest audiences in the unrest being depicted. Consequently, the relationship would anchor parallels between modern times and the events transpiring on stage. Additionally, composers would create scenes of immense spectacle and pageantry. This not only made it possible to demonstrate the state of the art stage technology of the Opéra, but in a way French Grand Opera served as the historical perspective of opulence—much as modern audiences might gleam from watching “Downton Abbey” or “The Crown” today.

So, why is Schiller’s “Don Carlos” such a good fit for the genre of French Grand Opera? Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) was greatly influenced by The Enlightenment Period and the American Revolution. Consequently, a principle theme of his work is the struggle for civil liberties. In “Don Carlos,” Schiller sets this within a historical context with the Spanish Inquisition. The cast of characters is based on real people, with the half-exception of the grand inquisitor—a title given to the priest in in charge of the inquisition. And though the Grand Inquisitor does not go by a proper name in the play or opera, a real person did hold this office. In reality, Prince Carlos was just as ruthless a theocrat as his father. Also, despite their age difference, King Phillip II and his teenage bride, Élisabeth de Valois, were happily married. Unfortunately, sometimes reality does not make for good theater. Schiller makes all of the characters into fully fledged adults, all of whom—save for the Grand Inquisitor—are dissatisfied with the current state of Spanish government; specifically its treatment of the newly Spanish Netherlands, which are agitating for their independence.

In Don Carlo, more so than in his other operas, Verdi’s Tinta is atmospheric. Beginning with the first scene in the monastery of St. Just, which opens with a monk chanting disparagingly about the vanity of the world, the musical landscape is dark and oppressive. This characterizes the Inquisition as an intangible weight hanging over the characters. Later, Verdi uses an Auto-Da-Fé to fulfill the requisite spectacle. The Auto-Da-Fé, which translates to “Act of Faith,” was a ceremony of public shaming during the Inquisition. People who ran afoul of the church—by broad and sweeping interpretations—were made to publicly repent for their crimes. Punishments would range based on the gravity and number of offenses. Individuals could face public humiliation in a manner similar to the cultural revolution of Maoist China. On the other hand, if they were guilty of an implacable sin, they would burn at the stake. The unfortunate justification was that the only way their soul could be cleansed and then accepted by God was through fire. However, for those individuals not being burned alive, the occasion called for much pomp and circumstance and festivities. Therefor the irony of the Auto-Da-Fé was the contrast between the grotesque punishments being meted out by the Inquisition, and the glitz and glamour of the noble spectators.

The scene opens with a jubilant chorus, which is shortly thereafter offset by the arrival of priests warning the assembled throng of the proximity of judgement day, and the need to repent. Verdi would deploy the same technique in Aida, where the somber music of the ancient Egyptian priesthood cast a pall on the triumphant return of the army. As in Aida’s ancient Egypt, Don Carlo’s Spain is a country in which the clergy are not solely religious leaders, but also the ruling class. The power of the Inquisition is on full display in the scene following the Auto-Da-Fé, where in his study Phillip II summons the Grand Inquisitor. The king has imprisoned his son for leading the Dutch independence movement and has sentenced him to death. Yet, as a father, he needs assurance that he is taking the right course of action, and not condemning his immortal soul for killing his son.

When the Grand Inquisitor enters, he is old, decrepit, and blind: the physical embodiment of the then-state of the church. Phillip and the Inquisitor’s duet, which is the foreboding Orwellian heart of the opera, grows out of the evasive responses that the Grand Inquisitor gives to a king in search of spiritual guidance. The Inquisitor goes as far as to compare King Phillip killing his son to God sacrificing Christ on the cross. From this response, it is clear how the inquisitor has corrupted core religious beliefs to suit a corrupt church’s mortal need for protection.

The Inquisitor further instructs the King to do away with Rodrigo—the Marquis of Posa, Carlo’s friend, and the King’s confidant—who is grooming Carlo to lead the Flemish resistance. Here, Phillip II is confronted with the prospect of not only killing his son but killing someone whom he considers his only friend. The king resists, but the Inquisitor retorts “So you need a friend! Why have the title of king if a lesser man is your equal?” The duet ends after the Inquisitor’s exit, when the king—now alone—apostrophizes: “must the throne always bow to the altar?”

While the king is one of villains of the piece, Verdi has written other royal figures that are far less sympathetic. By contrast, Phillip II is certainly guilty of acting in bad faith. But whether he has the power to act on his own free will is debatable.

By now, it is clear why Don Carlo is basically 1984 set in Golden Age Spain. However, Verdi leaves his audience with a glimmer of hope. And that hope is conveyed through the monk that appears in the monastery of St Just at the beginning of the opera. At the end, he reveals himself as Charles V—the Holy Roman Emperor, who ruled Spain at its height, and King Phillip II’s father. He was previously believed to be dead, but there was a rumor that he abdicated the throne for a religious life in the monastery. At the very end, he saves his grandson from the Inquisition, giving him sanctuary inside the monastery. This action sets him up as the diametric opposite of the Grand Inquisitor. Whereas the Grand Inquisitor represents a church corrupted by man, Charles V symbolizes the moral and spiritual purity of the church removed from the politics of the Spanish Inquisition.

At this point, the Prince has matured and is ready to lead the fight for Flemish independence. It is not clear what happens after Charles V rescues his grandson. But, at least for the moment, the Netherlands has a ray of hope to extricate itself from Spain’s theocratic dystopia.

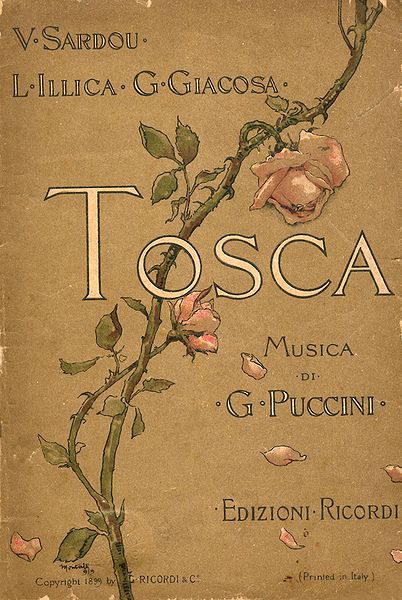

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Don_Carlo_de_Giuseppe_Verdi.jpg