And there in that land I encountered a strange race of people, to whom was the habit of an uncanny ritual. On bits they called paper – an artefact of plant material thinned into a sheet – they made marks. That these marks meant something, everyone believed, and concerning these marks on bits of paper they behaved strangely. As though to make a sacrifice, they folded these papers so as to fit into small coffins – which they called envelopes – and deposited them in larger coffins, which they called mailboxes. They insisted that by some strange means these artefacts – they called them letters – were conveyed to others, who could then interpret the marks; and that letters which they received daily were in turn from others living in distant lands, in whom they superstitiously believe.

For I watched and the same persons picked up and dropped off the letters, and I wondered at their incredulity to believe in such imaginary creatures in distant places when all the letters were delivered and gathered by the same persons. But the superstitious nature of this practice clearly goes deep, for I asked them how it was that they thought to convey meaning between themselves and these imaginary beings called “friends,” and they explained that it was by a practice called spelling – “spell” being a word in their language indicating a kind of incantation or magic…

– from “Notations of an Underworld Ambassador, Having Travelled to the Surface of the Earth and Chronicled What He Found There of Strange Customs and Manners Etc. To Which is Appended Maps and Other Useful Aids That Will Be of Consequential Help to the Reader, and Further Testimony of the Verifiable Truth of This Account and the Factuality Thereof Notwithstanding the Charges of Readers Whose Names Here Shall Not Be Named But Whose Words Have Spread Many Ill Things in the Public Realms That Are In No Way True of the Present Publishers Messrs. ____ and ____, Equire.”

As I write for the Inner Room, I find myself up against a particular difficulty. This difficulty is the double result of a society more interested in what I will call contemplatishness and mistyschism. These – as distinct from their more legitimate analogues, contemplation and mysticism – are commodified versions embraced by some as cognitive fashion accessories and rejected by others precisely because they function socially as such accessories. The tragedy is that, many times, both parties – those who embrace and those who reject – are unaware that what they are talking about is a ruse rather than the real thing. Mindfullness and so-called zen and such might be all the buzz, and might be rejected as all the buzz, but the real thing, the thing held in the real contemplative traditions, is different. It is also intuitively of far greater interest to normal everyday people than its fashionable mimes. Real contemplation and mysticism will not be a “life hack,” for this implies the twisting or bending of something naturally oriented in a particular direction. Rather, these practices will be a realignment with the nature of reality. And while one can discuss techniques and such, there is also a sense in which human intuition rightly ordered will tend toward these practices in the outworking of its longings and desires. As a writer for the Inner Room, I want to help you see not that you need contemplative spirituality etc. to make your life complete – as though it were some kind of value-added quality originally alien to your makeup. Rather, what I want to show you is that your being longs for this, and intuitively looks for it in everyday life. Practicing contemplative spirituality is not a matter of becoming a different person. Rather, it is a matter of becoming more of the person you are before God – though of course any good mentor would add that this should hardly be confused with some kind of narcissistic “search for enlightenment” or “self discovery” – the one who wants to save this life must lose it.

But how to convey all this? Hagiography proper often requires excessive translation to convincingly bring the life of the saint to bear on the modern world, while some modern theologies and narratives of spiritual messiness become just a little too comfortable and undisciplined in their messes. There had, I figured, to be some kind of middle way that can touch ground – and indeed an often awfully uneven and uncomfortable ground – even while not giving up the dream of heaven. And it is this precisely that I discovered in Love & Salt by Amy Andrews and Jessica Mesman Griffith (who co-hosts Sick Pilgrim here at the Patheos Catholic Channel).

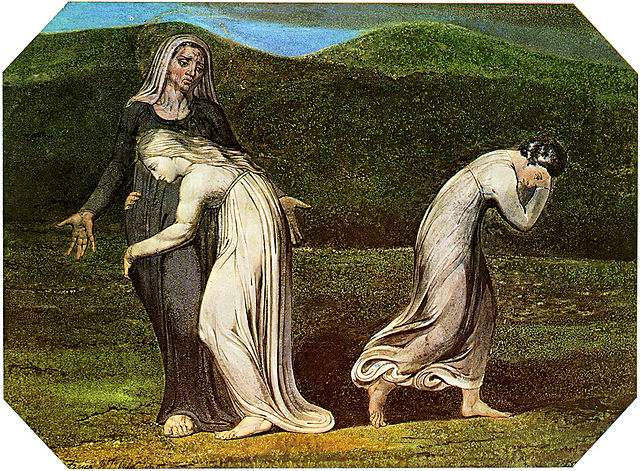

That letter writing and practices of friendship can be a part of mystical and contemplative spirituality is something I firmly believe – it is familiarity rather than any intrinsic quality that causes us to consider these matters in a sphere removed from our relationship with God. Hence, when one imagines one’s way out of this familiarity, one realizes that friendships and particularly communication via letters are not at all straightforward, and might even be seen as a little uncanny from the perspective of an outsider not used to them – and this was the point of my rather curious epigraphic piece of creative writing. We are familiar with letter writing because it is common – though perhaps less common now in a digital age than it used to be. However, if we look at it with fresh eyes, we might in fact see that there is still something of the spell in it, still something of the magic. As Amy notes in one of her letters:

The arrival of a letter is often the only sacramental thing in my day. I sit down quietly, by myself, for often I have saved it up for just the right moment, and then I lose myself in the world we have created between us – a world that includes our lives but cherishes them, and a world that includes God but makes him more explicit, which really means – I just looked it up – to unfold, smooth out, unroll him. We press God out in the pages of our letters, ironing and ironing, like two old-fashioned women. We mail him back and forth, and pile him up, like a basket of linen. (Amy, July 20, 2005)

Like any good title, the title of the book readily identifies its theme. It emerges from a quotation by Aristotle quoting a proverb saying that two people can’t know each other well “until they have consumed together much salt, nor can they accept each other and be friends till each has shown himself dear and trustworthy to the other,” (qtd. By Amy, June 12, 2006) and the point is that friendship is not simply a matter of shared interests or common goals – it is a matter of shared suffering as well – if we love together, we also eat salt together. And it is the interplay of these matters that give the book its evanescent quality, causing it to hover as it were between heaven and earth in a way that opens up sacramental space in the cosmos. Books about love simpliciter too often flatten the universe into two-dimensional sacharrine platitudes, while books about salt simpliciter run the risk of flattening it into an equally two-dimensional despair. But this book, like the real friendship it conveys, does neither, as each party calls to the other, one friend now entering the sorrow of the other or the joy of the other till the roles are reversed and it is her turn to receive. Watching the narrative unfold, I couldn’t help being reminded a little of Tolkien’s conception of eucatastrophe, where joy and sorrow meet behind the curtain and are effectively indistinguishable as they intermingle; as Jess puts it beautifully, “perfect joy could not be joy alone but must be a joy that somehow contains our past grief and sadness and longing.” (October 29, 2007)

Not, to be sure, that these conversations ever run the risk of necessitating suffering or trying to cheaply discern “how everything works out for the good in the end.” Indeed, part of the beauty of the book is the refusal to settle for any kind of cheap consolation that might lessen the grief and pain at the expense of truth and goodness. Some of the passages in this regard are harrowing, and though their focal point is for the most part the death of Amy’s daughter Clare, they speak to a number of sorrows shared throughout the book, including the death of Jess’s mother when she was a teenager. Jess, for instance, describes her role in Clare’s funeral:

At the Vespers we prayed for Clare on the eve of your due date, I read from Paul’s letter to the Corinthians: “O death, where is thy sting?” I practiced many times before the service, trying to get the cadence, the emphasis, just right. I wanted to convey to you my defiance in the face of death. I stood at the lectern and made the mistake of looking away from the little slip of paper printed with the readings, looking up at you and Mark. When I said the words, they came out all wrong, a little too loud and too fast, and despite all my practice, with the stress of all the wrong syllables. I hoped, walking back to my seat, that you hadn’t perceived my bravado. Where is thy sting? “It’s right here,” I wanted to say. “In my heart, in hers.” (Jess, August 2, 2006)

And later, in a similarly poignant passage, Amy wrestles with deep tragedy in the face of seemingly harsh and inexorable Scriptural texts:

You mentioned the book of Job in your last letter, so I started reading through it. You’re right; it’s hardly comforting. Job asks the same question I’ve been asking: “Where is the place of understanding?” And the only answer he comes up with is:

God understands the way to it,

and he knows its place.

For he looks to the ends of the earth

and sees everything under the heavens.

He made a decree for the rain

and a way for the lightning of the thunderThat God made a way for the thunder is all too clear, but where is our way? (Amy, March 13, 2007)

“Whither thou goest, I will go,” is the motto of the friendship from the beginning of the book – and indeed this is true. It is both beautiful and terrifying the way that these friends are able to take into each other the pain and joy they share. They embody the grace needed to give; the even greater grace needed for that humbler act of receiving; and the still even greater grace needed to open-handedly let friendship survive what can feel like crushing imbalances of grief, joy, and pain. In reality, all our joys and pains are always our own – they are also always that of our friends and neighbours. But because we subdivide our lives into petty economies and make a fuss about who has more and who has less and what place on the scale each person’s suffering falls, we too often approach friendships with a set of hierarchies of pain and joy – matching, comparing, and balancing; calculating how much sympathy we can get here; how much we can afford to give there. In true Christian friendship (which, to clarify, I do not necessarily consider coterminous with friendship between Christians), these longstanding habits begin to fall away in favour of an openness that gives and receives rather than counting and calculating. What makes this possible is a particular kind of stubborn, grace-infused commitment to friendship and communication, and it is precisely this that I want to propose as a kind of everyday mysticism that is as easy to practice as our closest friend.

To be sure, it can’t be fully premeditated; there is a large measure of grace and surprise in it, and Love & Salt describes the initial meeting of Jess and Amy as a miracle, and friendship cannot be other than that. But though we depend on gift for that initial spark, there is also a discipline to kindling it into a flame. Friends must be committed to mutual and regular communication; they must be hospitable and honest with one another; they must be present to themselves and to each other – or must at least strive for these things. And in this striving one can also discern God if one looks for Him. If this sounds weird, perhaps that is because it is – but no less weird than the gospel itself, which proclaims that we unfold Christ’s life in our lives to each other in a manifold variety of ways. If, as Christ said, they will know we are Christians by our love, this book articulates the implied complement – that they will know we are humans – friends – by our shared salt.

There are far too many things I love about this book, and not least the surprises along the way, the moments when a particularly normal or mundane moment opens into something truly sacramental in which neither earth nor heaven cancel each other out – the bush burns, but is not consumed. Indeed, these occasional moments are precisely the heart of the book and the things most difficult to capture; where these letters are most contemplative and mystical, they are so in the most unassuming and casual of ways, which makes their evanescent quality difficult to chronicle. Still, if these jewels are perhaps too rare to be removed from their context and put on display, I can and hope have at least given a bit of context regarding the settings of silver that frame these apples of gold. They are means within our reach – simple acts of friendship and letter writing, love and salt. In a world in which contemplation and mysticism have become rarified and commodified things, it is refreshing and encouraging to find God simply and truly pressed out in the pages of these letters between friends.